Introduction

Globally, ocean and coastal acidification (OCA) threatens marine ecosystems and the livelihoods of coastal communities. OCA has negative impacts on commercially important species as well as coastal and marine ecosystem services. Acidification is caused by the ocean’s absorption of about a quarter of global carbon dioxide emissions, which lowers seawater pH and decreases the availability of critical chemical building blocks for marine life. Coastal acidification refers to processes in the nearshore environment where these effects on seawater chemistry are further influenced by local factors, including freshwater inputs, nutrient pollution, biological productivity, and upwelling.

Unlike other climate-related challenges such as sea level rise and flooding, there is a dearth of extensive planning and adaptation tools for community and industry preparedness for OCA. As atmospheric carbon dioxide is the root cause of ocean acidification, the main mitigation policy is reducing carbon emissions. However, along the coast, OCA has additional spatiotemporal drivers and diverse social impacts that challenge the development of comprehensive policy or social solutions. Nonetheless, OCA can be partially addressed by reducing local stressors that exacerbate impacts, and through adaptation that supports population resilience across at-risk species and ecosystems. Doing so requires sustained, coordinated activities that involve individuals, scientists, nonprofit organizations, industry, regulatory agencies, and coastal communities. These groups have previously been called “stakeholders,” but here we use the terms “participants,” “interested parties,” and “community members/partners” (Reed and Rudman, 2023).

The National Sea Grant College Program aims to enhance the practical use and conservation of coastal, marine, and Great Lakes resources. In support of this mission, Sea Grant funds research, education, and extension projects that improve community understanding of emerging issues, including OCA. Staff and funded researchers of the Sea Grant network have formed partnerships with a variety of organizations. These partners have enabled Sea Grant to make significant advances in monitoring capabilities, translation of research into aquaculture and fisheries applications, education and participatory science opportunities, and policy blueprints.

This article reviews Sea Grant OCA efforts by examining a variety of data sources and sharing illustrative case studies to emphasize advances and highlight issues that have received less attention to date. It aims to provide insights on and examples of opportunities for advancing OCA-related partnerships and applied research.

Methodology

To provide complementary perspectives and obtain a broad view of the Sea Grant network’s contributions to OCA, three different sources of information were reviewed: (1) bibliographic data looking at Sea Grant scientific publications from the Web of Science, ProQuest, and the NOAA National Sea Grant Library; (2) Sea Grant’s internal Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation Resources (PIER) database, which captures funded research projects and their reported impacts and accomplishments (I&As);1 and (3) the news media databases Factiva and ProQuest Global Newsstream to review Sea Grant outputs via mainstream news channels. The keywords “acidification” and “Sea Grant” were searched, limiting results to 2008–2023, except for the PIER database where records were captured for 2008–2021. To be included, bibliographic records had to be about OCA and involve either a Sea Grant-affiliated author or a source of Sea Grant funding or support. The analysis began in 2008 to match the starting year of dedicated Sea Grant OCA funding. The results obtained for funded projects and I&As were reviewed by their respective program research coordinators for consistency and to identify missing information, including contacting programs that had no OCA related projects or I&As for verification.

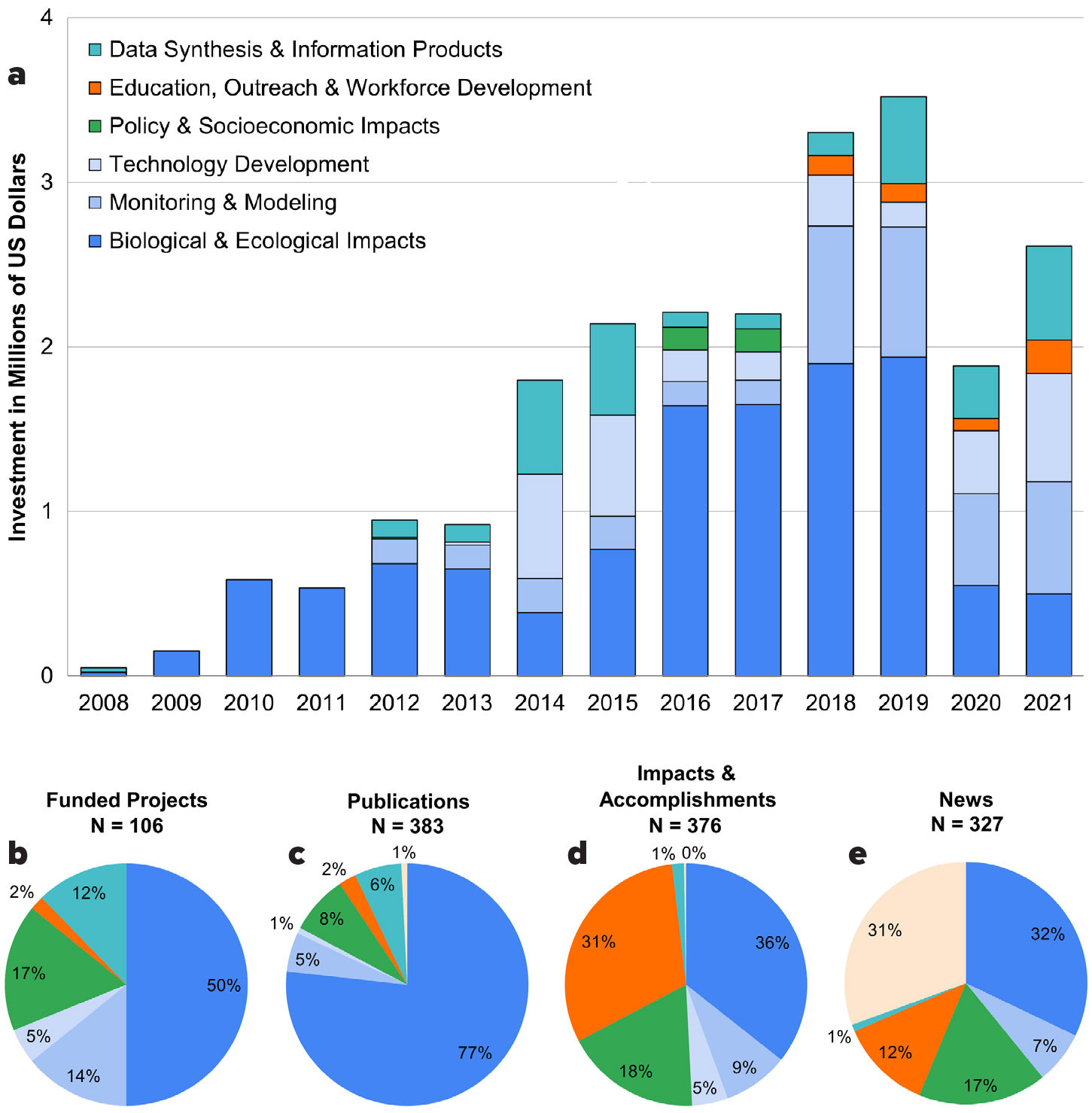

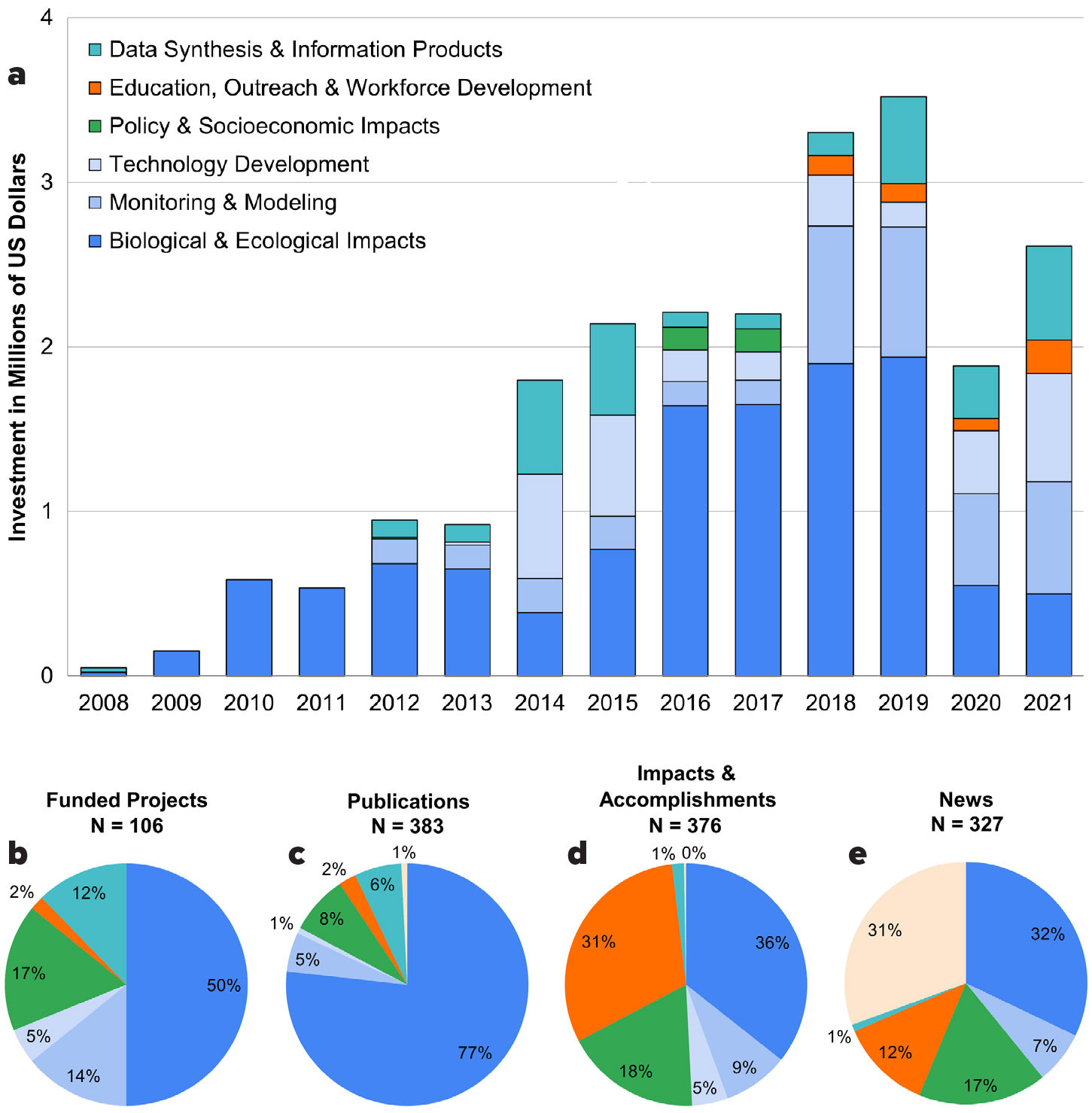

Based on their primary focus, search results were categorized as: (1) Monitoring & Modeling, (2) Technology Development, (3) Biological & Ecological Impacts, (4) Policy & Socioeconomic Impacts, (5) Data Synthesis & Information Products, and (6) Education, Outreach, & Workforce Development. Categories are consistent with themes identified by the Interagency Working Group on Ocean Acidification (IWG-OA, 2014), with slight modifications, such as combining Monitoring and Modeling. We considered the first three categories as Research and when multiple categories applied, assignments reflected the primary focus. Results from the processed bibliographic and the news media searches are provided in the online Supplementary Materials.

1 I&As are brief summaries that, in view of the authoring Sea Grant program, highlight accomplishments or measurable impacts that expanded the reach of the project, encompassing a variety of measurements such as the economic value for an aquaculture industry or the number of students supported.

Results

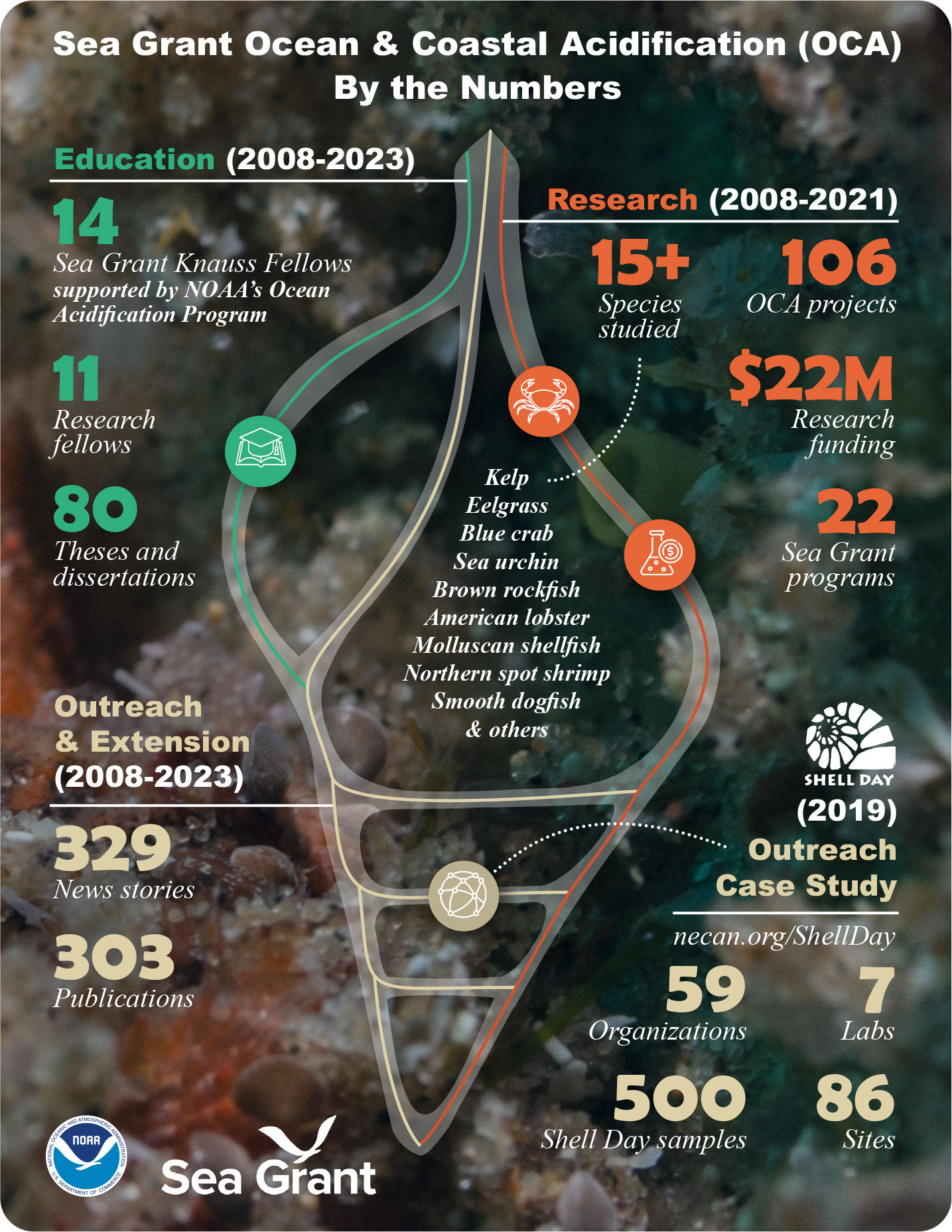

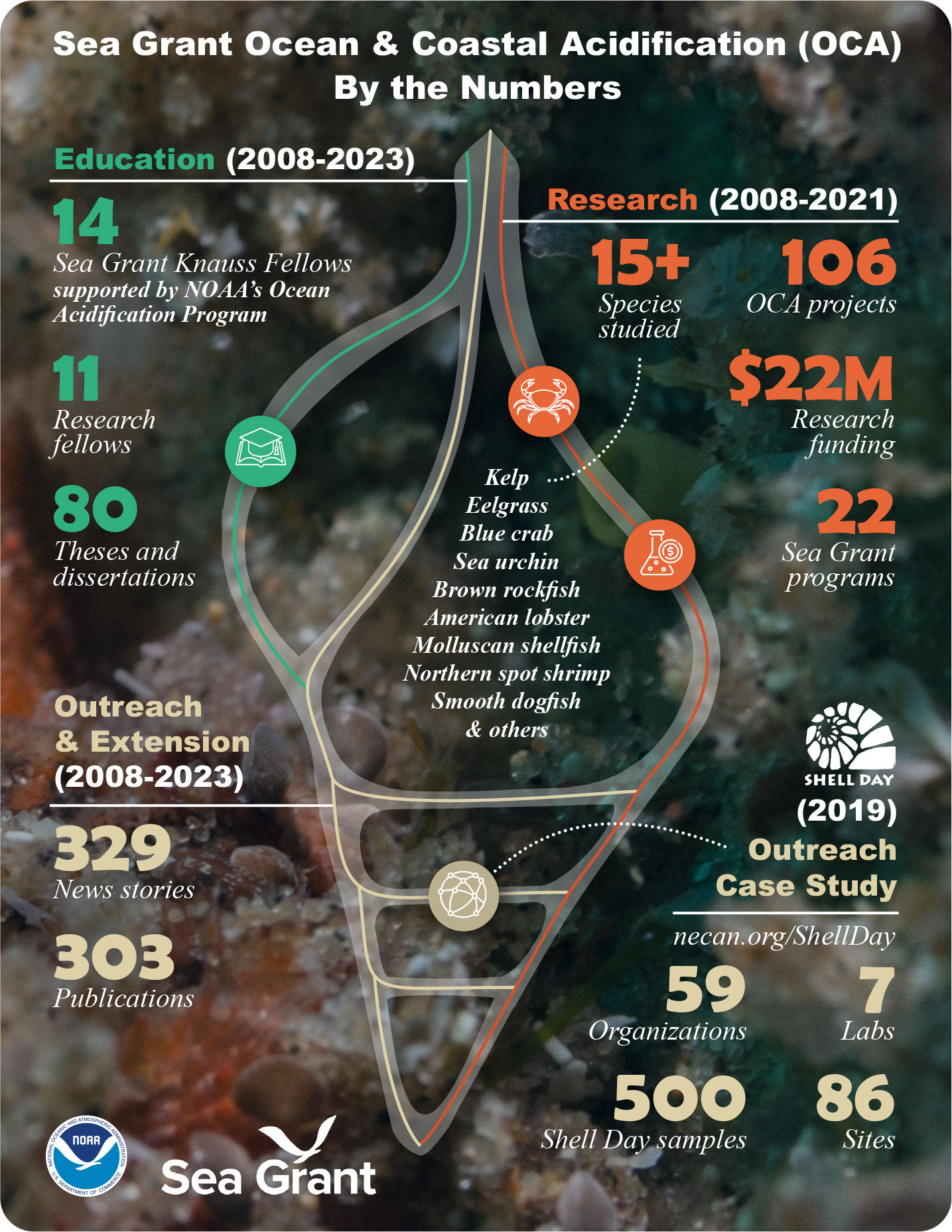

As part of a broader initiative, Sea Grant has provided resources to regional and state efforts aimed at understanding how OCA is affecting US waters and living marine resources. From 2008 until 2021, Sea Grant funded 106 projects across 22 programs, reflecting a total investment in research and related projects of more than $22M, which includes the required 50% non-federal match per the Sea Grant authorization (33 US Code § 1123). Funding increased gradually during this period, with less than $1M invested per year until 2013, more than $3M in 2018 and 2019, and then a decrease to levels similar to 2013 in more recent years (Figure 1a). Since 2009, research (Figure 1a, blue-shaded categories) has consistently received about 70% of those funds, with more diversification towards other categories since 2014.

FIGURE 1. (a) Sea Grant investment (millions of USD) in ocean and coastal acidification categories from 2008 through 2021. Distribution in categories (%) of (b) the number of funded projects, (c) peer-reviewed articles and theses from bibliographic databases, (d) impacts and accomplishments, and (e) news articles. Note that the category “other,” which is not included in the legend, mostly refers to budgetary topics only relevant in news articles (e, cream color). > High res figure

|

Half of the 106 projects investigated the consequences of OCA on marine species, mostly those of commercial relevancy and overall ecosystem importance (Figure 1b). This fundamental research has spanned a wide range of species—including cultivated molluscan shellfish, American lobster, Northern spot shrimp, brown rockfish, sea urchin, smooth dogfish, blue crab, eelgrass, kelp, and others—and has informed ecological vulnerability assessments. This funding emphasis is also reflected in the significant numbers of peer-reviewed publications and theses (77%), I&As (36%), and news articles (32%) focused on Biological & Ecological Impacts (Figure 1c–e). Sea Grant’s investments in other research categories are wide ranging and have contributed to developments in high-resolution modeling, observational networks, novel sensor technologies, genomics and selective breeding, and isotopic methodologies for paleoclimate assessments.

Non-research efforts received 30% of funding, but Policy & Socioeconomic Impacts; Education, Outreach, & Workforce Development; and Data Synthesis & Information Products collectively accounted for 50% of the I&As and 30% of the News articles (Figure 1d,e). A noticeable portion of News articles (31%), categorized as “Other,” centered on budgetary issues that did not fit into the categories used to characterize the data. Most of these News articles covered congressional publications and testimonies at federal and state levels about the relevance of funding NOAA and Sea Grant OCA efforts.

Research

The volume of peer-reviewed publications stemming from Sea Grant-funded studies attests to the program’s impact on OCA research. The number of publications paralleled the trend in Sea Grant OCA investments, increasing steadily between 2008 and 2018 before leveling off at about 40 contributions per year. The Research Case Study in Box 1 further describes Sea Grant’s investments in OCA research and workforce development since 2016.

Policy & Socioeconomic Benefits

Sea Grant’s initial contributions to OCA policy work emphasized the Pacific Northwest, especially Washington state—the first state to recognize and formally respond to this emerging threat (see Box 2). Sea Grant programs have continued to play an important role as other states developed their own OCA action plans and legislation. For instance, the results from California Sea Grant research on OCA refugia were used to support the development of California bills authorizing OCA monitoring, research, and the creation of a state advisory board. Similarly, Sea Grant science features prominently in a 2021 report to the Massachusetts Commonwealth that includes a suite of policy recommendations to address the socioecological and socioeconomic impacts of OCA (MCOA, 2021). Other contributions are described in the Discussion.

Data Synthesis & Information Products

Because Sea Grant works with both scientists and the public, it is well positioned to synthesize OCA findings and tailor information products for a variety of users. An early example is “20 Facts About Ocean Acidification,” a list of talking points designed to facilitate consistent messaging by the OCA research community at a time when public awareness was low. As the field has advanced, Sea Grant has been able to pursue increasingly sophisticated products for a broad range of end users. Recently funded projects include tools for ecosystem assessment, fisheries management, and shellfish cultivation.

Education, Outreach, & Workforce Development

Sea Grant staff and partners have made substantial contributions in this realm: 80 graduate students received training from Sea Grant-funded researchers between 2008 and 2023, as evidenced by the number of OCA-focused theses and dissertations submitted during that period (accounting for 21% of bibliographic data or publications in Figure 1c). Similarly, NOAA’s OAP office provided funding support for 14 Sea Grant Knauss Policy Fellows’ postgraduate experiences in OCA during this period; Berger (2021) describes further impacts of this partnership. The Outreach Case Study described in Box 3 illustrates how Sea Grant engages the broader public in learning and contributing to OCA solutions.

Discussion

Our results illustrate Sea Grant’s multifaceted approach to understanding and addressing the challenges imposed by OCA on ecosystems, economies, and cultures (Figure 2). We show how targeted investments at state, regional, and national levels have advanced scientific and government OCA agendas and amplified investments and outcomes through diverse partnerships. Here, we consider how this approach and the strengths of the Sea Grant network have already advanced OCA priorities and could play a crucial role in future efforts to address climate change.

FIGURE 2. This infographic summarizes the Sea Grant network’s contributions in ocean and coastal acidification since 2008 through research, education, extension, and outreach. Many of these contributions were made possible through partnerships, as detailed in the three case study boxes. Shell Day numbers are included here as an outreach example in the northeastern United States in which Sea Grant programs were fundamental partners. Graphic by Lily Keyes, MIT Sea Grant Communication Specialist. > High res figure

|

Sea Grant funds projects that are responsive to interested parties’ concerns and that facilitate adaptive management strategies for responses to local environmental and societal impacts. This funding results in the development of policy, industry, and educational partnerships that have continued impact beyond Sea Grant’s initial investments and the timescales of individual research projects. This is evident in the relative distribution of categories across information sources in Figure 1b–e. Although Funded Projects and Publications results emphasized Research themes (blue categories), the Impacts & Accomplishments (I&As), and News results showed how Sea Grant successfully translated that research into outcomes in Education, Outreach, & Workforce Development and in Policy & Socioeconomic Impacts. Another example of this long-lasting and diversified impact is Sea Grant’s emphasis on support of graduate students for individual projects as well as for fellowships with partner investments, ensuring that early-career scientists have the training necessary to advance OCA research and policy.

One of Sea Grant’s strengths in facilitating and communicating OCA research is the extension network, which serves as a trusted, neutral source of cutting edge, science-based information. Extension and engagement activities coupled to research initiatives extend and communicate results on complex topics to those who stand to benefit most. In five of the six US Coastal Acidification Networks (CANs), Sea Grant program staff have served as steering committee and working group members, facilitating communication and collaboration among interested parties involved in CAN activities, including scientists, resource managers, policymakers, and industry members. Sea Grant programs have also consistently provided funding for and organized activities to advance the strategic priorities of regional CANs. For example, Alaska Sea Grant facilitated the Alaska Ocean Acidification Network Tribal Working Group to center the priorities of Alaska Natives, enabling Tribal leadership of expanded nearshore OCA monitoring.

Another Sea Grant strength is flexibility as Sea Grant staff are equally adept as project leaders and partners. Sea Grant has played both roles in two important West Coast OCA efforts that developed in parallel: the Olympic Coast Ocean Acidification Sentinel Site and the Olympic OA Regional Vulnerability Assessment (OA-RVA). Washington Sea Grant (WSG) helped launch and lead OASeS for several years, and currently serves on its roundtable-style steering committee as an equal partner. WSG also co-led the OA-RVA, but intentionally designed this community-based participatory research collaboration to center Tribal priorities and agency. Sea Grant’s commitment to supporting partnerships helps ensure that interested parties are engaged and empowered to respond to OCA.

Climate change continues to challenge our ability to adapt and become more resilient. Increasing frequency and intensity of extreme events has fueled interest in novel ocean-based climate mitigation strategies such as marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR). This topic has received serious attention from the OCA research community due to substantial overlap in expertise and instrumentation, as well as significant government and private sector investment. Sea Grant is well positioned to support mCDR research and engagement and can also help build the skilled workforce that will be needed to deploy mCDR on a meaningful scale.

Sea Grant’s robust programmatic structure, which integrates research, extension, and education activities, can generate impactful and scientifically grounded outcomes that shape the future. As Sea Grant plays an integrative role across research institutions, decision-makers, and coastal industries, we encourage our Sea Grant network and partners to take this opportunity to foster collective action and support science-informed decision-making to address the novel challenges posed by climate change in marine ecosystems and society.

Additional Coastal and Ocean Acidification Resources

20 Facts About Ocean Acidification

https://wsg.washington.edu/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/outreach/ocean-acidification/20-facts-English.pdf

Funded Research Projects – MIT Sea Grant

https://seagrant.mit.edu/all-projects/

Marine Resources Advisory Committee

https://oainwa.org/mrac/

NOAA Ocean Acidification Program

https://oceanacidification.noaa.gov/

Ocean Acidification. Northeast Sea Grant

https://www.northeastseagrant.com/initiatives/ocean-acidification

Shell Day

http://necan.org/ShellDay

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Davies from the NOAA Library, and Claire Berman and Alejandro Paz from MIT libraries; the Sea Grant Research Coordinators Network for help with quality controlling the research projects and I&As; students Isabella Yeung, Reyna Ayala, Yousef Khan, and Susie Josephson who helped with searches; and Jessica Dupree from the National Sea Grant Office for help with PIER queries. We also thank Lily Keyes, MIT Sea Grant Communication Specialist, who graciously designed Figure 2 and proofread the manuscript; the organizers of this Sea Grant special issue of Oceanography; and two anonymous reviewers who made contributions for improvement. We acknowledge support to CB by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sea Grant award #NA22OAR4170126; to MC by the WSG 2020-2024 Liaisons with PMEL award #NA19OAR4170380; to JR by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Sea Grant award #NA22OAR4170122; to RAB by NOAA National Sea Grant Office.

Disclaimer

The results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or the Department of Commerce.

> High res box

> High res box > High res box

> High res box > High res box

> High res box