INTRODUCTION

Solutions are urgently needed for the complex challenges facing our social-ecological systems. These “wicked” problems demand innovative and unique approaches to create solutions that benefit both human and natural communities—the foundation of sustainability science (Clark and Dickson, 2003). The process of knowledge co-production has gained increasing attention for generating policy-relevant, solutions-oriented, and socially robust knowledge, and is one of the key concepts consistently discussed as the most effective strategy for mobilizing knowledge in the context of evidence-informed policy and practice (Bandola-Gill et al., 2023).

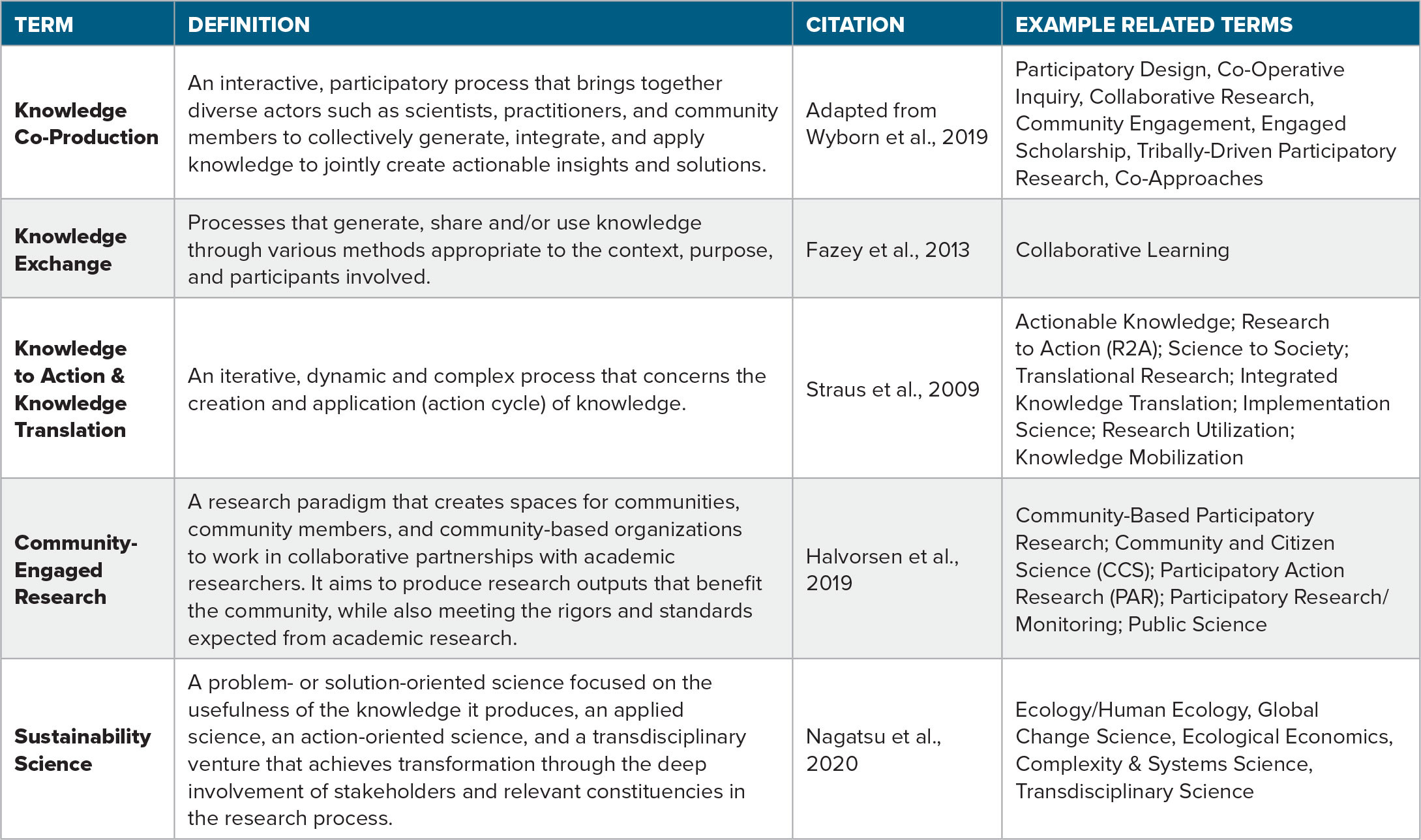

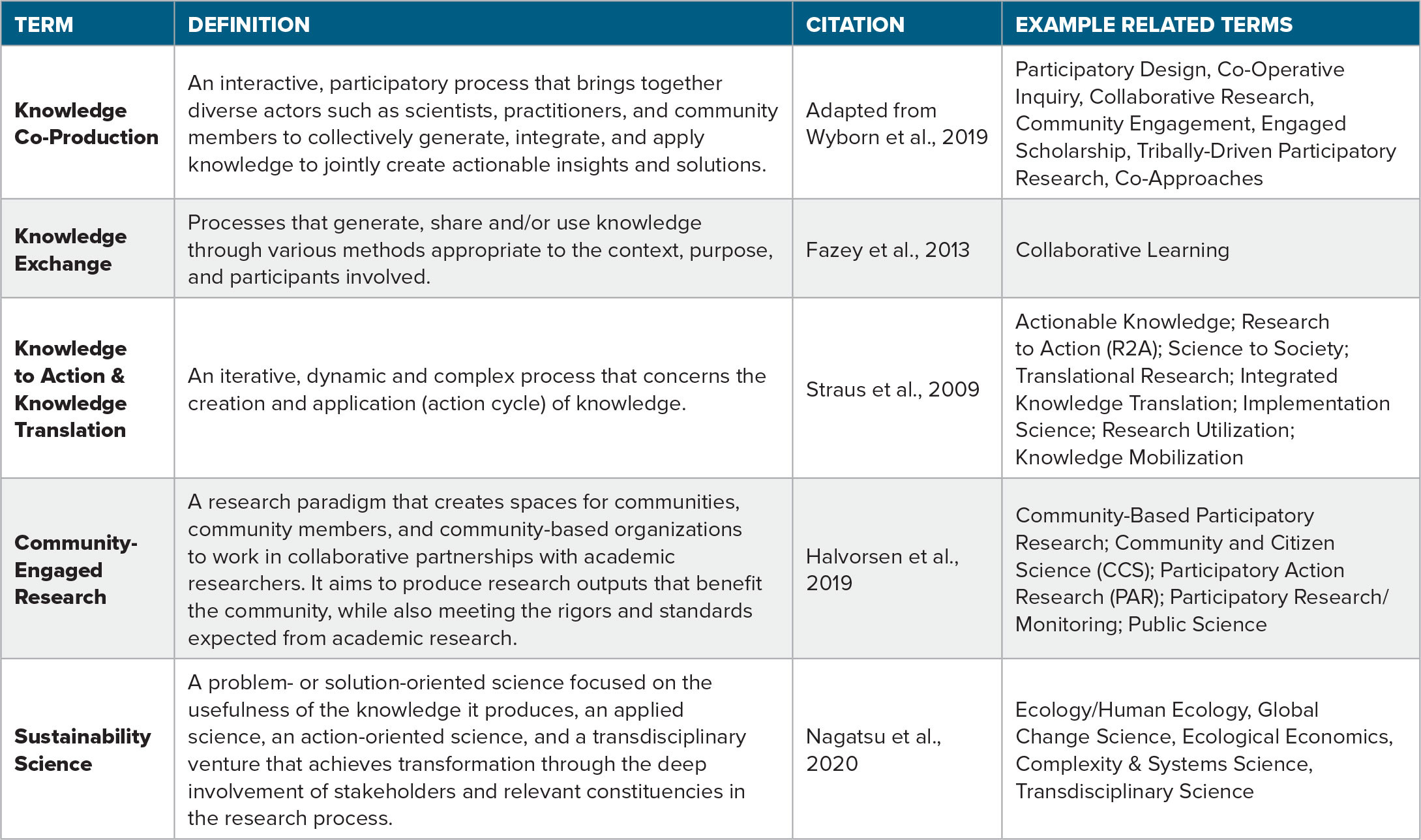

Knowledge co-production has been widely practiced in the public health field for decades and more recently has been adopted as one of the most important concepts in research and practice for global sustainability (Miller and Wyborn, 2020). Knowledge co-production and related concepts have many definitions and may mean different things to different actors in different contexts (Wyborn et al., 2019; Bandola-Gill et al., 2023; Table 1). We define knowledge co-production for sustainability as an interactive, participatory process that brings together diverse actors such as scientists, practitioners, and community members to collectively generate, integrate, and apply knowledge to address complex sustainability challenges.

TABLE 1. Common terminology for knowledge co-production and participatory approaches for sustainability. > High res table

|

This approach extends beyond a single epistemology (e.g., Western scientific methods) and embraces diverse forms of knowledge generation, such as traditional, Indigenous, and local knowledge (Dixon, 2016). It incorporates interdisciplinary perspectives, those that exist across different life experiences and occupations, and those that are fundamentally connected to place (Ardoin et al., in press). Collaboration and knowledge co-production with societal actors, such as decision-makers and local community members, are particularly important for projects where concrete societal change and implementation of solutions is a main objective, as these individuals are often the most closely engaged with or impacted by the scientific question or issue at hand (Bandola-Gill et al., 2023). The benefits of knowledge co-production include: better quality of research and conceptualization of complex systems; strengthening ownership and buy-in; building public trust in evidence-based decision-making; stronger inclusion and equitable knowledge generation; and strengthening innovation, implementation, and overall success of sustainability initiatives (Wyborn et al., 2019).

The sustainability field’s eager uptake of knowledge co-production approaches is reflected in its proliferation in related literature, governance venues, and funding requirements (Arnott et al., 2020b; Norström et al., 2020; Vaughn and Jacquez, 2020). Some knowledge co-production frameworks and practical guides exist in related domains, such as in the context of urban and mental health (Roper et al., 2018; Audia et al., 2021); food, energy, and water systems (Kliskey et al., 2021); fisheries research (Cooke et al., 2020); early career professionals in ocean sustainability (Satterthwaite et al., 2022); Indigenous Peoples in Arctic research (Ellam Yua et al., 2022); co-design (Moser, 2016); and actionable science (Beier et al., 2017). Additionally, principles have been described for knowledge co-production in sustainability research (Norström et al., 2020). Yet, relatively few resources offer a framework and practical guidance related to knowledge co-production in sustainability science, such as assessing when knowledge co-production is appropriate and how to navigate the process based on available resources (e.g., time, funding, relationships) and project partners’ values.

The goals of this paper are to provide: (1) a novel and synthetic framework with concrete phases, key questions, strategies, and crosscutting themes for engaging in knowledge co-production for sustainability; (2) examples that illustrate how the process has worked in practice; and (3) recommendations for further advancing diverse participation in knowledge co-production for sustainability.

METHODS

This paper synthesizes the existing literature across different fields and combines the narrative review with lessons from practical experiences to provide an applicable, overarching framework for knowledge co-production in the context of social-ecological sustainability. We use the term “coastal communities” to refer to people across communities of place, practice, identity, and interest with connections to any coastal and marine habitat, including estuaries, nearshore coastal regions, open ocean habitats, and the Great Lakes. We use the terms “participants,” “interested parties,” and “community members/partners” to encompass the broad range of actors interested in and/or affected by a process, including but not limited to those who have a stake, share, right, or interest in a particular question or issue. Thus, we explicitly choose to not use the term stakeholder to be more inclusive of the various types of actors engaged in knowledge co-production and as a step toward decolonizing language used in research (following Reed and Rudman, 2023).

The framework is a product of synthesizing existing literature from structured searches (e.g., Google Scholar) using terms related to “knowledge co-production” (Table 1) and supplemented with literature contributed by the authors. It has been co-designed by the authors through an iterative process of reading, synthesizing, discussing, and writing. Practical insights are drawn from the authors, who collectively bring experience as natural and social scientists and Sea Grant personnel working at the interface of scientific research, policy, and resource management in aquatic social-ecological systems. Geographically, the authors span ocean, coastal, and Great Lakes regions of the United States, work across local and regional contexts, and range in experience from early to late career. The professional experiences with and reflections on co-production are shaped by technical training as scientists; experience approaching this work from an evidence-based lens; and designing, leading, or facilitating these processes. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that the authors represent just a fraction of those involved in co-production processes. This limitation underscores the opportunity for further inclusive development of the framework, potentially through co-production with community members, planners, managers, and local and indigenous partners. The intention is to integrate theory with collective expertise from practical experience to promote critical thinking and ongoing discussions and to provide interested researchers and practitioners with the skills necessary to engage in knowledge co-production.

ADAPTIVE, ITERATIVE WHEEL OF KNOWLEDGE CO-PRODUCTION

Introduction to the Wheel

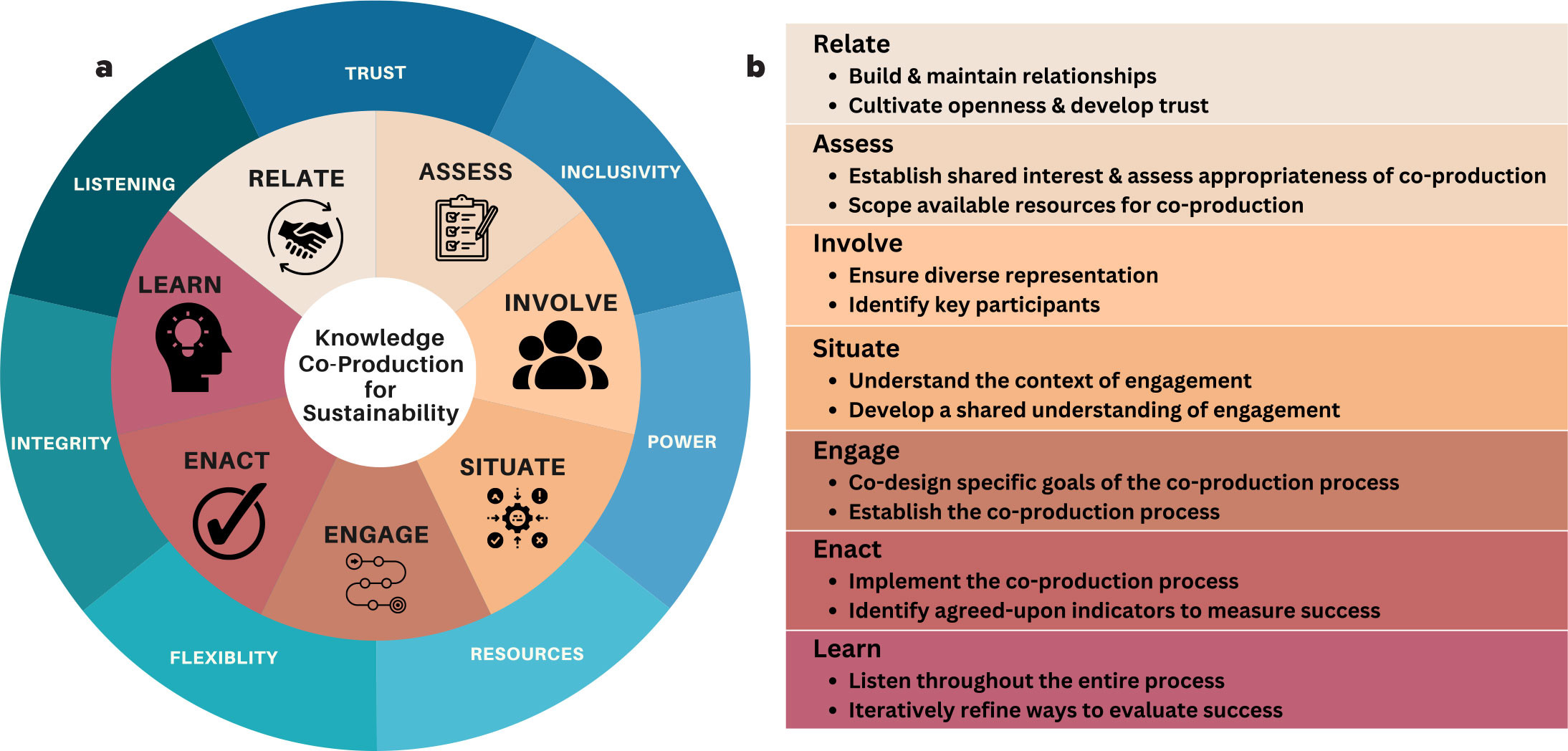

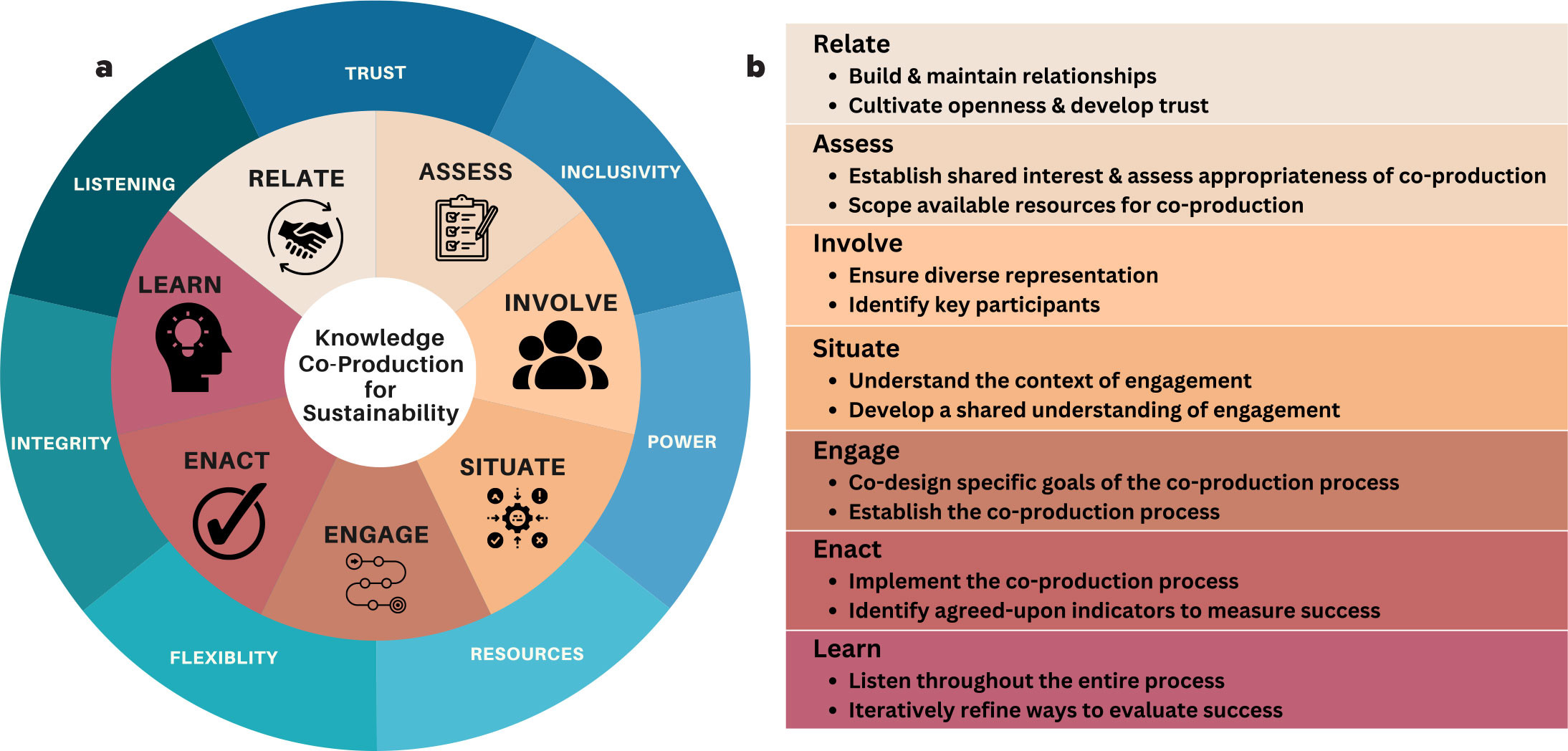

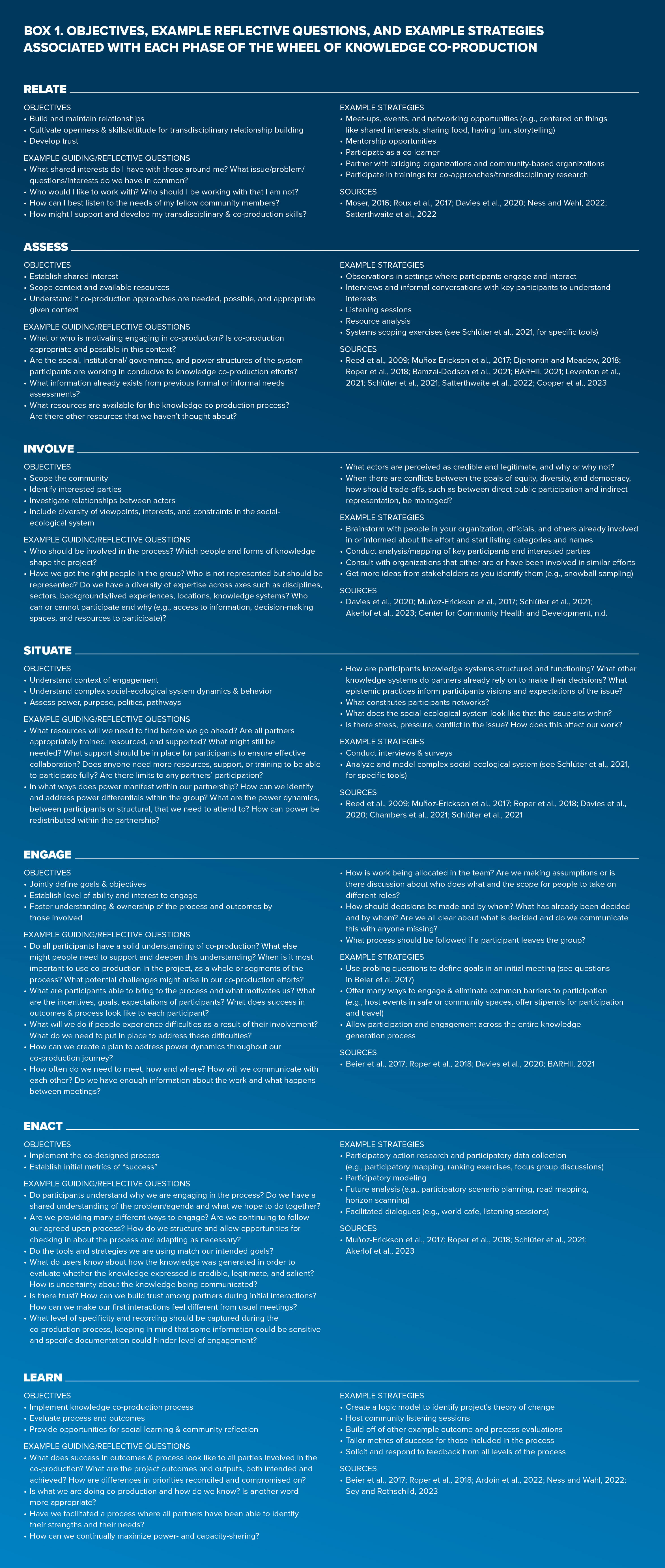

The wheel of knowledge co-production is a synthetic framework for implementing co-production approaches in sustainability sciences (Figure 1). The wheel consists of seven interconnected phases (inner circle; Figure 1a) and objectives within each phase (Figure 1b) that guide the knowledge co-production process with crosscutting, foundational themes woven throughout (outer circle; Figure 1a). Although presented in phases, it is a responsive, iterative, and adaptive process of equitable engagement that is nonlinear, may not proceed through all phases, and allows for continuous learning, relationship building, and adaptation throughout and beyond a single project. For simplicity, the foundational themes (denoted as Themes in text) have been described in a relevant phase; however, each of the foundational themes are considered essential to the process as a whole and are not bound within a particular phase. The wheel emphasizes the importance of building trust, understanding context, and co-designing with the community for meaningful and impactful outcomes. Key questions and strategies are included to help assess whether co-production is appropriate for the situation and how to successfully navigate a given phase (Figure 1; Box 1).

FIGURE 1. (a) Wheel of Knowledge Co-Production for Sustainability. There are seven phases (inner wheel; red shades) and foundational themes (outer wheel; blue shades). The seven phases are separate elements of a co-production process that may play out in sequence but in practice are more likely to be parts revisited non-sequentially. The process is nonlinear, iterative, and may occur over many cycles. The foundational themes include listening, trust, inclusivity, power, resources, flexibility, and integrity. (b) Corresponding summarized objectives are highlighted for each phase. > High res figure

|

Relate Phase

The Relate Phase sets the foundation for collaboration, emphasizing trust, empathy, and effective communication (Figure 1; Boxes 1–3).

The process of co-production often begins by identifying the people or groups who share common interests or values regarding a place or topic of focus. The intent is to build and maintain relationships rooted in trust and collaboration, which requires early engagement in or prior to the co-production process, allowing nuanced understanding of one another, the situation, context, or place of focus and for the creation of shared goals. Sustained long-term engagement, beyond grant cycles, is equally important to allow for the longer timescales often required to observe outcomes related to complex issues (Kliskey et al., 2021).

Humility is a cornerstone of authentic relationship building and is necessary for cultivating openness and developing trust (Liboiron, 2021). Trust plays a crucial role in knowledge co-production by fostering openness, transparency, and effective communication among interested parties (Theme: Trust; Norström et al., 2020). This leads to knowledge sharing, learning, and innovation, and increases the likelihood of honest collaboration, cooperation, and collective ownership of co-produced knowledge.

Assess Phase

The Assess Phase promotes reflection on the appropriateness of co-production methods in a given context (Figure 1; Boxes 1–3; Lemos et al., 2018).

It is important to establish shared interest and assess appropriateness of co-production. This includes considering why a co-production approach may be valuable to the challenge at hand, who has helped to shape the question(s) needing to be answered, and what is motivating the use of co-production approaches. Contextual factors are also important to consider, including pre-existing relationships and power dynamics among actors, or social norms that legitimize different forms of knowledge (Turnhout et al., 2020). A commitment to sharing power among partners is a vital piece of collaborative processes that can result in increased trust and genuine inclusion of partners’ priorities (Themes: Power, Trust, Inclusivity), so it is important early on to agree upon the degree to which power and decision authority will be shared (Shirk et al., 2012).

Given mutual motivation to pursue a co-production approach, it is then critical to scope the available resources for co-production such as the time and capacity available (Theme: Resources). Co-production approaches require more time, funding, and specialized skill sets, such as facilitation and conflict mediation, as compared to less participatory approaches, and these resources must be identified and committed prior to beginning the co-production process (Beier et al., 2017).

Involve Phase

The Involve Phase is pluralistic and focuses on inclusivity, diversifying participation, and involving a wide range of people with varied perspectives and expertise (Figure 1; Boxes 1–3).

Successful knowledge co-production requires ensuring diverse representation (Theme: Inclusivity; Enengel et al., 2012). Participants coming from different personal and professional backgrounds and holding differing authorities are likely to bring different types of knowledge, understandings of the problem, interpretations, perspectives, methods, ideas for solutions, and norms of engagement, debate, and collaboration (Norström et al., 2020). On the one hand, this diversity can foster innovative and creative research and learning that benefits both the local and the scientific communities. On the other hand, there may be conflicting needs, goals, or values. It is important to anticipate these dynamics and attend to them as they arise so that all participants have equitable access to the process and have their perspectives heard (see references in Vohland et al., 2021).

One effective way to identify key participants and ensure diverse representation is to collaborate with established community organizations, such as boundary organizations1 and community-based groups. Because these organizations have established relationships and credibility within the community, they can facilitate direct engagement with key individuals, especially those who may be underrepresented or marginalized or respectfully represent the perspectives of community members who may not have the capacity to participate individually (Cash et al., 2003). Inclusion decisions should seek to balance local expertise with external support to better integrate diverse knowledge systems and to foster mutual learning and capacity building.

Situate Phase

The Situate Phase delves into understanding the context of engagement, including power dynamics, social structures, and governance systems (Figure 1; Boxes 1–3).

Each process of knowledge co-production is situated in a particular place, with a particular group of people, to address a particular problem or set of problems that are bound by a specific geography or framed by a broader issue (Nörstrom et al., 2020). In practice, how context is acknowledged and responded to determines whether the process of knowledge co-production is empowering for participants, whether the process and outcomes hold legitimacy, and whether the knowledge co-produced is relevant and impactful (Zurba et al., 2022).

Successful co-production is a process of “with” not “for,” relying on developing shared understandings of engagement including participation, commitment, and objectives. It recognizes the self-determination of communities and Indigenous governance to approve or deny research (Zurba et al., 2022). It includes discussions of implicit and explicit perceptions, assumptions, and power (Theme: Power). Although it bucks a natural tendency to depoliticize co-production processes, power dynamics and inequities should be directly acknowledged and addressed (Turnhout et al., 2020, and references therein).

Engage Phase

The Engage Phase focuses on identifying specific goals and co-designing engagement, allowing participants to actively shape the knowledge generation process (Figure 1; Boxes 1–3).

Throughout this phase it is critical to co-design the goals of the co-production process through open, constructive dialogue among participants. Goals of the co-production process may be outcome or output oriented. Outcomes could include overcoming conflict, developing a shared understanding of an issue, defining a common vocabulary to address an issue, or ownership of research; outputs could include development of an actionable research tool or generating a publication of relevant/responsive/actionable research (Chambers et al., 2021). A portion of the established goals should be attainable within the planned project timeline while others may be longer term, achieved through continued partnership over time.

There will never be a “one-size-fits-all” approach to knowledge co-production, so it is important to collectively establish the co-production process (Schlüter et al., 2021, and references therein). Engagement level may vary based on goals and resources. Some processes may warrant full collaboration with a subset of participants, while targeted input can be solicited from others at specific stages. Additionally, co-production should strive for comprehensive representation, potentially expanding the group over time. However, to streamline the process, a core advisory group may need to be formed through mutual agreement (Beier et al., 2017, and references therein).

Effective co-production requires adaptability on the part of all participants as key details of the process evolve (Theme: Flexibility). Therefore, the project’s scope and intended outcomes should allow the flexibility to meaningfully respond to participant input, including iteratively adapting project goals and processes as needed.

Enact Phase

During the Enact Phase, participants implement the co-production process. The end goals of this phase can vary and may take the form of research, specific actions, product development, or solutions to identified challenges (Figure 1; Boxes 1–3).

Implementation will be tailored to the key players, goals, and context. Often, activities within this phase can involve a combination of formal/informal and individual/small/large group interactions, but at least one meeting where all contributing parties are present is recommended (Beier et al., 2017, and references therein). In co-production processes it is important that “the resulting knowledge is perceived by participants and other end-users as credible, salient, and legitimate” (Theme: Integrity; Norström et al., 2020). Transparent communication on project scope, timelines, data, and goals establishes trust with communities, empowers community members, and democratizes project ownership. At its best, the process of knowledge co-production empowers decision-making and develops leadership in community members (Turnhout et al., 2020).

Identifying agreed-upon indicators to measure success, both before and during the enact phase, simplifies and enhances the transparency of the evaluation process, increasing the likelihood of achieving actionable change. Co-defining project benchmarks (e.g., reaching a certain milestone by a given date), values (e.g., inclusiveness, grounded in Indigenous epistemologies), and outcomes (e.g., educate a certain audience on a given topic) solidifies a shared understanding of the project’s ultimate purpose and approach (Cooke et al., 2020).

Learn Phase

The Learn Phase emphasizes the importance of listening, evaluation, and reflection. This enables participants to learn from and during the co-production process and adjust strategies as needed, fostering continuous improvement and innovation (Figure 1; Boxes 1–3).

Listening throughout the entire process is important in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the co-designed process related to shared goals (Theme: Listening). This involves assessing implementation through unbiased, honest observation and reflection by all involved. Since impact and success can have various interpretations, assessments should be flexible and accommodate different perspectives on “success” among participants. Various principles of knowledge co-production may be used to assess the process: “context-based” aligns with the situation, “pluralistic” assesses diversity and mobilization of knowledge, “goal-oriented” targets outcomes, and “interactive” emphasizes the quality and evolution of interaction between participants (Norström et al., 2020).

As with the knowledge co-design process itself, the Learn Phase is iterative, with continuous refinement of implementation and evaluation strategies (Wyborn et al., 2019). Evaluation throughout the project allows for reflection on strategies that are serving or hindering project success, may reveal whether a pivot in the project goal or approach is necessary, and ultimately provides a way to share the story of the project’s impact.

THE ROLE OF BOUNDARY ORGANIZATIONS IN KNOWLEDGE CO-PRODUCTION

The National Sea Grant Program as an Example

While many programs and funded projects support co-production of knowledge, Sea Grant’s unique program model provides a structure that can overcome many of the challenges associated with participatory science frameworks and support the crosscutting guiding themes for knowledge co-production. The federal-academic partnership allows Sea Grant programs to tailor specific research priorities to address needs within their local communities, which are informed through extensive two-way feedback with partners. Case studies presented in Boxes 2 and 3 were selected to showcase how the theoretical assumptions of the wheel of knowledge co-production are grounded in practice and reflect examples across a diversity of participants, type of work, and maturity of projects. These case studies (Boxes 2–3), while not exhaustive, serve to highlight particularly noteworthy phases and themes in each process. Additionally, they illustrate the significant role of boundary organizations in knowledge co-production, exemplified by Sea Grant. Sea Grant’s interdisciplinary approach and strong emphasis on centering communities in knowledge co-production provides a powerful platform for connecting researchers, communities, and practitioners to collaborate toward actionable solutions (Jones et al., 2021).

DISCUSSION

Boundary organizations can facilitate knowledge co-production by sharing membership across communities, translating across norms and vocabularies, and sustaining relationships and engagement over extended time periods. However, the journey toward effective knowledge co-production may present challenges (Jones et al., 2021) and may not always be the best approach for a given context. In many cases, clear incentives for engaging in co-production may not exist or may not align across participants; not all audiences value diverse forms of knowledge; there may be reluctance to engage in actionable science due to lack of training or interest; or the right venues for building initial relationships across people in different sectors or communities may not exist. Addressing these challenges is crucial, and this is where boundary organizations, like Sea Grant, along with other institutions and funding agencies, can make a significant impact. The unique role of boundary organizations and the functions and qualities of knowledge brokers should be recognized and further leveraged in advancing knowledge co-production efforts (Goodrich et al., 2020).

The wheel of knowledge co-production (Figure 1, Box 1) and the illustrative case studies (Boxes 2–3) highlight a few key recommendations for boundary organizations and those seeking to incorporate knowledge co-production approaches into their work. First, consider working with or through established knowledge brokers. These organizations’ positions and standing relationships within communities can provide context to help researchers understand which communities are well served and which may be underserved and thus could benefit most from additional research. Assessment could extend beyond a project’s funding period to capture the scope of measurable societal impact. Knowledge brokers can also help facilitate explicit conversations on incentives for co-production and navigate differences in needs across participants; provide relevant training in skills such as communication, engagement, and facilitation; apply social sciences and methodologies in an interdisciplinary context to help understand and address sustainability challenges; promote actionable knowledge; and develop environmental literacy to empower community members with the skills and knowledge needed for active participation in co-production efforts.

Funders can play a crucial role in incentivizing and rewarding knowledge co-production as well (Arnott et al., 2020a). Seed funding enables relationship and trust building, while longer-term grants reduce the pressure of continuous grant writing, allowing for more time spent engaging across phases of the knowledge co-production cycle. To make this process more intentional and authentic requires reimagining grant criteria, for example, in the development of requests for proposals (RFPs) that outline clear engagement objectives and evaluation criteria, shifting the focus from “box-checking” to genuine engagement and long-term relationship building. Additionally, providing longer lead times (e.g., many months at the minimum) for funding calls, funding all phases of the knowledge co-production cycle, and supporting participation costs (e.g., stipends, travel, meals, childcare) can allow partners to develop relationships (Relate), establish shared interest (Assess), identify key participants to include (Involve), understand the context of engagement (Situate), and co-design the goals and process (Engage) prior to carrying out the agreed upon project (Enact). These shifts in funding can further support genuine and sustainable knowledge co-production.

CONCLUSION

Our Iterative Work Ahead

This paper underscores the value of knowledge co-production as an interactive, participatory process that brings together diverse actors such as scientists, practitioners, and community members to collectively generate, integrate, and apply knowledge to address complex sustainability challenges. It serves as a guide for understanding when and how co-production can be effectively employed in community-based endeavors. As evidenced by examples from the National Sea Grant Program, co-production is a flexible, adaptive process, and projects do not all follow the same path. Some projects may even target specific phases of the process and therefore may become embedded within a larger, longer-term co-production process, spanning many projects.

We hope that the wheel of knowledge co-production (Figure 1) and associated resources (Boxes 1–3 and additional readings) provided in this paper serve as a valuable starting point for researchers, practitioners, and communities engaged in or considering knowledge co-production approaches. Achieving knowledge co-production is a journey that involves learning, practice, and the gradual development of genuine and trustworthy relationships. Those who aim to promote this collaborative mode of work are in a constant state of learning and adaptation, which can extend into decision-making venues and participatory governance. Furthermore, we envision it as a cornerstone for shaping a collective vision of the central role that knowledge co-production plays in advancing actionable and equitable research. We hope that this work stimulates critical new thinking on how to address complex sustainability issues by centering communities in an equitable and inclusive process of shared knowledge generation and lays the foundation stones for a path toward realizing this vision.

ADDITIONAL READING

-

Cockbill, S.A., A. May, and V. Mitchell. 2019. The assessment of meaningful outcomes from co-design: A case study from the energy sector. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 5(3):188–208, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.07.004.

-

Collins, H., and R. Evans. 2007. Rethinking Expertise. University of Chicago Press, 176 pp.

-

Cordell, D.F., and D. Tanzi Smith. 2016. Being a transdisciplinary researcher: Skills and dispositions fostering competence in transdisciplinary research and practice. Chapter 6 in Transdisciplinary Research and Practice for Sustainability Outcomes. Routledge.

-

CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force. 2011. Principles of Community Engagement, 2nd ed. NIH Publication No. 11-7782, National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC, 193 pp., https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf.

-

-

NRC (National Research Council). 2009. Informing Decisions in a Changing Climate. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 200 pp., https://doi.org/10.17226/12626.

-

-

Osterblom, H., C. Cvitanovic, I. van Putten, P. Addison, R. Blasiak, J.-B. Jouffray, J. Bebbington, J. Hall, S. Ison, A. Le Bris, and others. 2020. Science-industry collaboration: Sideways or highways to ocean sustainability? One Earth 3(1):79–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.06.011.

-

Pandya, R.E. 2014. Community-driven research in the Anthropocene. Pp. 53–66 in Geophysical Monograph Series, 1st ed. D. Dalbotten, G. Roehrig, and P. Hamilton, eds, Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118854280.ch6.

-

Rittel, H.W.J., and M.M. Webber. 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences 4(2):155–169, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730.

-

Vindrola-Padros, C., L. Eyre, H. Baxter, H. Cramer, B. George, L. Wye, N.J. Fulop, M. Utley, N. Phillips, P. Brindle, and M. Marshall. 2019. Addressing the challenges of knowledge co-production in quality improvement: Learning from the implementation of the researcher-in-residence model. BMJ Quality & Safety 28(1):67–73, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007127.

-

Voyer, D.M., and D.J. van Leeuwen. 2019. ‘Social license to operate’ in the Blue Economy. Resources Policy 62:102–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.02.020.

-

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is with heartfelt gratitude that we acknowledge all those who played a vital role in helping to shape the ideas and experiences that brought this paper to life. We are grateful to Carrie Culver who helped to shape the initial ideas, the California Deep Ocean DDT Assessment participants and Leadership Team (Lian Guo, Charlotte Stevenson, Amulya Jasti, Leah Shore), and community volunteer partners of the NH Volunteer Beach Profile Monitoring Program. Additionally, we are appreciative of two anonymous reviewers whose feedback substantially improved the manuscript. The scientific results, conclusions, views, and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of NOAA or the Department of Commerce.

FUNDING

EVS was supported by a partnership among CalCOFI participants, including Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO), NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center (SWFSC), California Department of Fish and Wildlife (#P2370003), and California Sea Grant (NA20OAR4170258 and NA22OAR4170106). LM was supported by the National Sea Grant Federal Partnership Program (NA21OAR4170155) and Louisiana Sea Grant (NA23OAR4170159). AAA was supported by University of Southern California Sea Grant (NA22OAR4170104). JMR was supported by California Sea Grant (NA22OAR4170106) and the Delta Stewardship Council (DSC19124-A1). ALE and WJC were supported by NH Sea Grant (NA22OAR4170124) and University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension. AND was supported by Oregon Sea Grant (NA22OAR4170102) and Oregon State University. RJO was supported by The William and Eva Price Fellowship Program. NW was supported by the Ohio Sea Grant College Program (NA18OAR4170100), The Ohio State University. RAB was supported by NOAA National Sea Grant Office. CB was supported by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sea Grant (NA22OAR4170126). ELS was supported by the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium (NA22OAR4170090) and Mississippi State University. KAG was supported by the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve (TJR2023).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

This manuscript was actively co-produced by the authors through engaging synchronously and asynchronously in discussions and in research and writing. All authors contributed to each major step in the development process of the manuscript, including concept or design of the article; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of information for the article; drafting the manuscript; critically revising many iterations of the manuscript; approving the version to be submitted and agreeing to be accountable for the work (Appendix S1). Additionally, many authors supported care work throughout the process, which is “a form of political and ethical practice that ‘holds things together’” (Liboiron et al., 2017, and references therein). Visually representing the authors in a spiral symbolizes that all authors were part of the collective knowledge co-production process to develop this manuscript.

> High res box

> High res box > High res box

> High res box > High res box

> High res box