Full Text

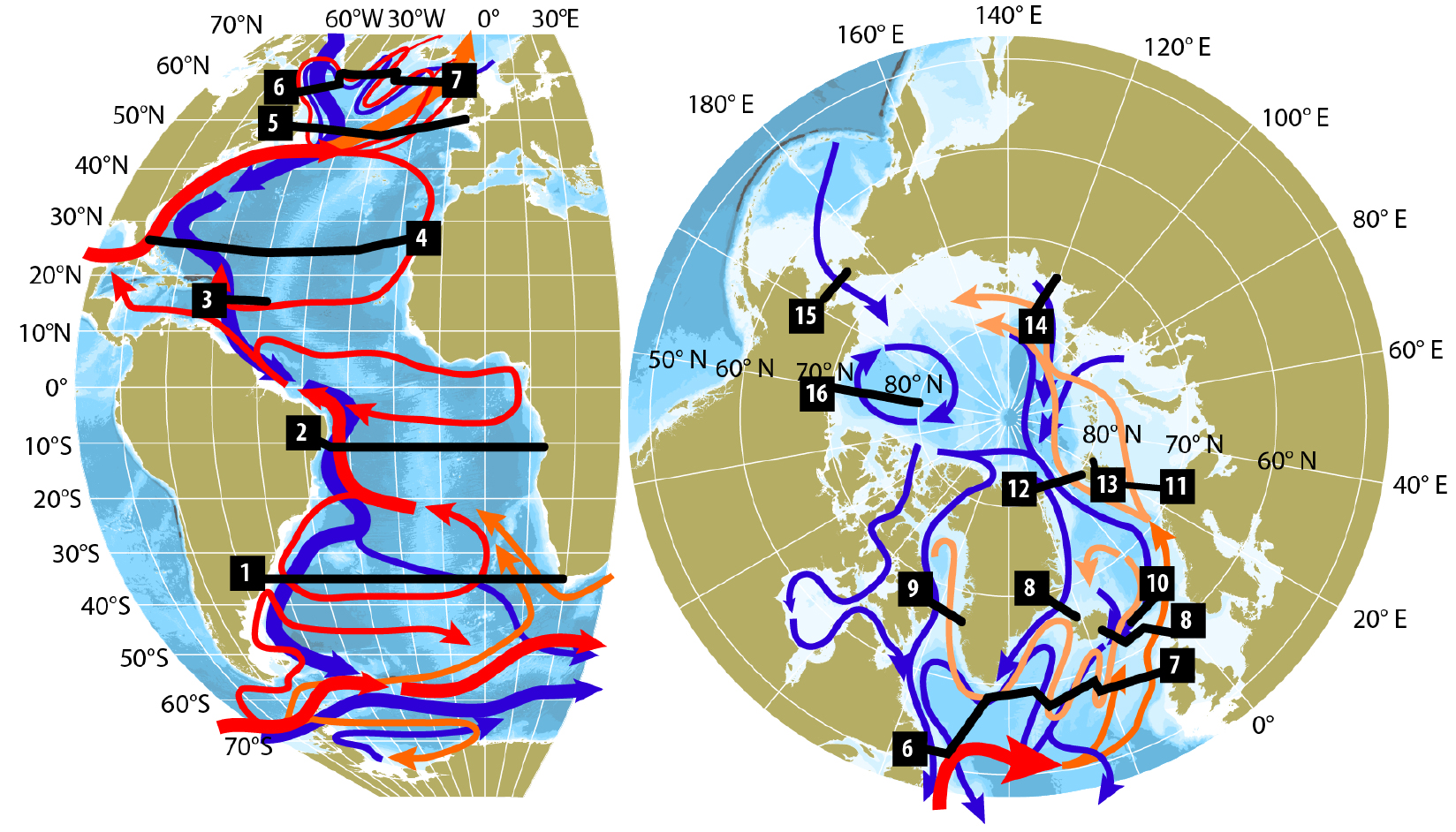

Ocean circulation redistributes heat, freshwater, carbon, and nutrients all around the globe. Because of their importance in regulating climate, weather, extreme events, sea level, fisheries, and ecosystems, large-scale ocean currents should be monitored continuously. The Atlantic is unique as the only ocean basin where heat is, on average, transported northward in both hemispheres as part of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). The largely unrestricted connection with the Arctic and Southern Oceans allows ocean currents to exchange heat, freshwater, and other properties with polar latitudes.

A number of observational arrays, shown in Figure 1, together with the main circulation features, have been established across the Atlantic and in the Arctic Oceans to improve our understanding of and to monitor changes in the AMOC, as well as large-scale changes in water mass properties (e.g., temperature, salinity) and ocean transports (how much heat or salt is transported by currents). The arrays incorporate multiple observing platforms such as ship-based hydrographic transects, submarine cable measurements, moored sensor arrays (see Figure 2) at a number of latitudes, surface drifters, satellite observations, expendable bathythermographs, and Argo floats (Frajka-Williams et al., 2019; Østerhus et al., 2019).

|

|

These observational arrays contribute to the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) via the Observing Coordination Groups (OCG) networks. Increasingly, interdisciplinary and international collaboration are ensuring that these arrays quantify more than solely the physical ocean circulation and its transports of heat and salt. For example, sensors that can detect oxygen and nitrate concentrations, pH, the partial pressure of CO2, and seawater optical properties have been added, along with water samplers, to a number of arrays to quantify biogeochemical fluxes.

|

|

While the building blocks of the arrays are nationally funded and organized (often with shorter funding periods that can jeopardize the sustained effort), it is the international collaboration and coordination that makes them truly basin-wide and allows them to bridge borders and disciplines. Moreover, the data collection efforts often bring opportunities for testing technological advances and for training early career scientists and those from developing nations.

Existing observations have greatly advanced our knowledge of large-scale ocean circulation variability at various timescales and provided first insights into its links to weather, ecosystems, and regional sea levels. The arrays continue to provide new and essential knowledge of oceanic processes. This leads to better representation of the physics in ocean and coupled models and, consequently, to reduced uncertainties in climate and operational predictions. Sustained observations remain critical for monitoring and understanding how Earth’s climate system responds to global warming and for assessing the imprints of this response on society’s development of climate adaptation strategies. It remains important to reconcile the results from different arrays using new technologies and improved methodologies in order to reduce uncertainties in the estimates of oceanic transports. Continued global collaboration, evaluation of the different critical components of the observing system, improving visibility of the observational array components in GOOS, and engagement with end users will be critical to ensure the sustained effort of these arrays.

In summary, the global community has been obtaining critical environmental information by measuring ocean transports at different locations in the Atlantic and at the Arctic Ocean gateways. Continued efforts based on these observational arrays are paramount to understanding and adapting to the impacts of climate and weather on humans and Earth’s natural resources on land and in the ocean.