Introduction

Given the rate and societal impact of ongoing human-caused warming, understanding the geographical extent, magnitude, and frequency of past global climate variations is essential. Ocean temperature is a critical parameter in the climate system. While sea surface temperature reflects heat exchange between the ocean and atmosphere, as well as large-scale ocean circulation, the average temperature of the upper ocean (0–1,000 m) is a useful estimate of upper ocean heat content. Thus, a top priority in paleoceanography is to provide accurate proxy-based ocean temperature reconstructions across all timescales (millions to hundreds of years). This information, gleaned from geological records, is essential for validating numerical models used to project future change and to inform policymakers who are developing strategies for mitigation and adaptation.

Efforts to reconstruct past surface and bottom water temperatures have expanded to include the polar regions (e.g., Shevenell et al., 2011; Fietz et al., 2016), where reliable instrumental temperature data are only available for the past 100 years (e.g., Hansen et al., 2010; IPCC, 2019, and references therein). Part of the impetus for this focus is the revelation that retreating grounding lines accompanied by warming ocean waters are resulting in Antarctic ice sheet mass loss and global sea level rise (Jacob et al., 2012; Rintoul et al., 2018). Furthermore, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states with high confidence that “both polar oceans have continued to warm in recent years, with the Southern Ocean being disproportionately and increasingly important in global ocean heat increase” (IPCC, 2019).

As calcium carbonate microfossils are not always continuously preserved in high-latitude sediments (e.g., Zamelczyk et al., 2012), paleoceanographers turn to non-carbonate-based molecular fossils to determine past variations in high-latitude ocean water temperatures (e.g., Sluijs et al., 2006; Bijl et al., 2009; Shevenell et al., 2011). Lipids preserved in marine sediments that have been successfully used in paleotemperature reconstructions include algal alkenones and archaeal isoprenoidal glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (isoGDGTs), which are sensitive to temperature change and relatively resilient to degradation compared to other lipids (e.g., Huguet et al. 2008; Zonneveld et al., 2010; Schouten et al., 2013; Herbert, 2014, and references therein). For example, the most mature of these paleothermometers, the alkenone unsaturation index UK37, was developed in 1986 (Brassell et al., 1986) and is widely used to reconstruct sea surface temperatures (e.g., Ho et al., 2013; Herbert, 2014, and references therein). Subsequently, the archaeal isoGDGT-based paleotemperature proxy known as the TetraEther indeX of 86 carbons, TEX86, was proposed (Schouten et al., 2002) and well received by the organic geochemistry community.

One advantage of proxies that employ archaeal membrane lipids is that these molecules are ubiquitous in globally distributed marine sediments, making them useful for calibration and estimating low-to-high latitude thermal gradients (Schouten et al., 2002). However, as with all proxies, researchers have discovered a number of non-thermal factors that affect the distribution of isoGDGTs in marine sediments. Because archaea occupy almost every niche on Earth, a number of studies have been undertaken to improve our understanding of archaeal distribution, ecophysiology (e.g., Hayes, 2000), and membrane molecular structure (e.g., Chugunov et al., 2015).

Here, we review current knowledge of the archaeal isoGDGT paleotemperature proxies, including the recent hydroxylated isoGDGT (OH-isoGDGTs) paleothermometer. We focus our review on recent insights gained from using these archaeal membrane lipid paleothermometers in the polar regions.

Archaeal Membrane Lipids and Paleothermometry

Membranes are the interfaces between (micro)organisms and their environments. The key roles they play in metabolism (e.g., providing energy to the cell using ion gradients across the membranes; Konings et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2020) and environmental sensing and signaling (Ren and Paulsen, 2005) require constant composition adjustments (Oger and Cario, 2013). Archaea synthesize tetra-ether lipids that span the entire membrane and form a monolayer (Koga and Morii, 2007). The isoGDGTs are a subset of these archaeal tetraether lipids, and their composition is group specific; for example, Thaumarchaeota preferentially synthesize isoGDGTs with cyclopentane rings (Sinninghe Damsté et al., 2002). Archaea also produce OH-isoGDGTs (Lipp and Hinrichs, 2009) that were first discovered in methanotrophic archaea (Hinrichs et al., 1999) and later in Thaumarchaeota (Elling et al., 2017; Bale et al., 2019).

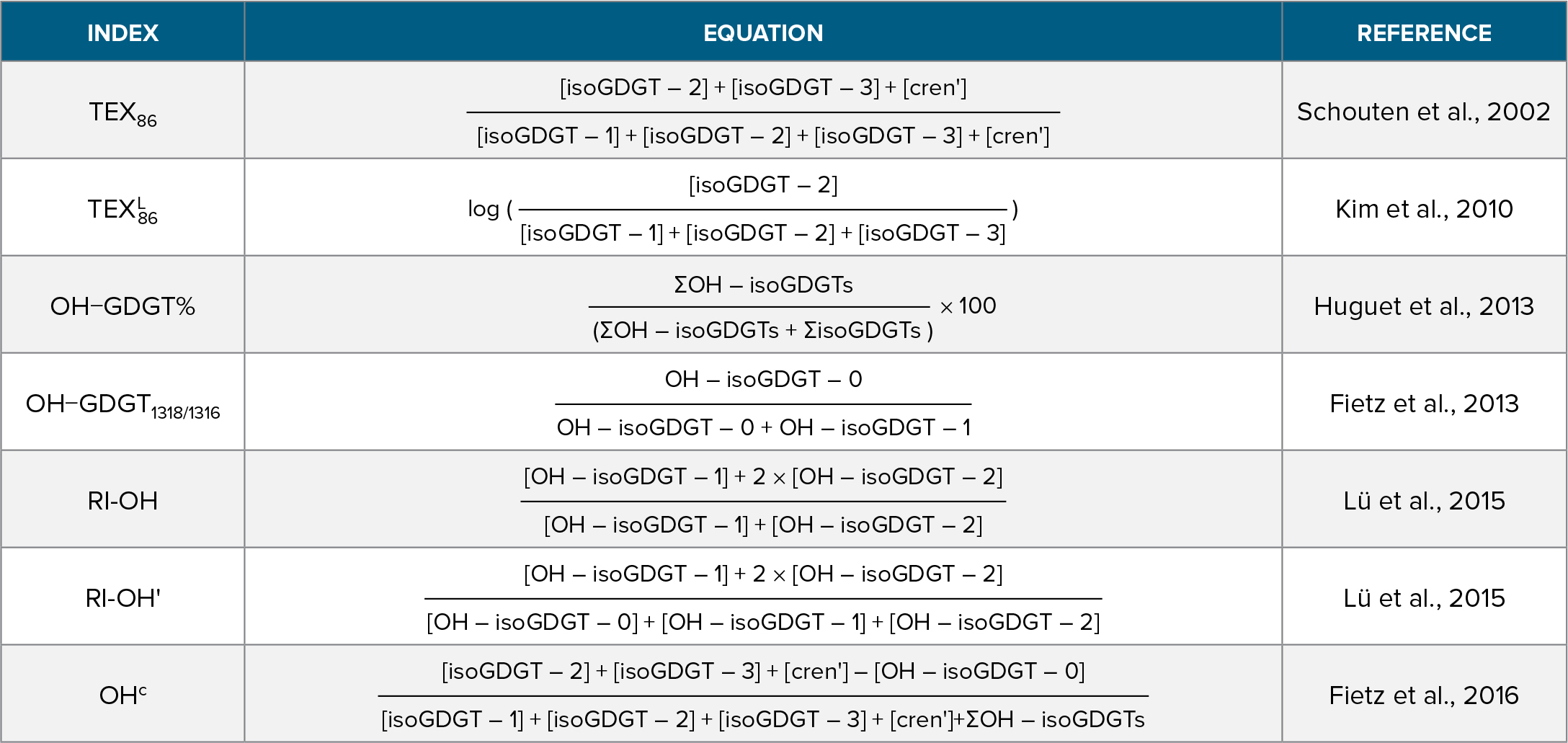

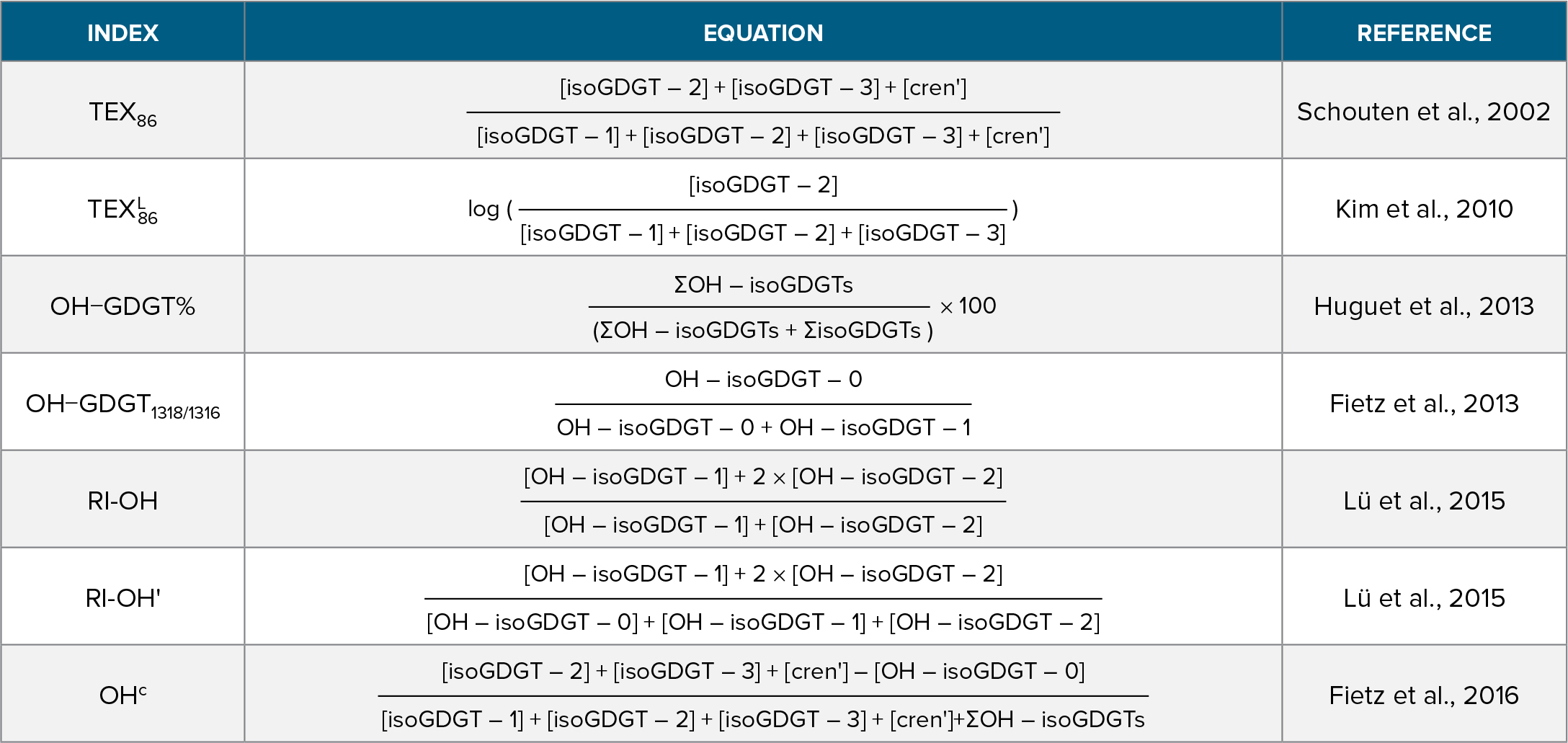

The stability of archaeal membranes increases with ambient growth temperature, especially in thermophilic extremophiles (De Rosa et al., 1980). Yet, it was not until the 2000s that geochemists exploited this observation to develop quantitative temperature proxies (e.g., Schouten et al., 2002; Kim et al. 2010; Ho et al., 2014; Tierney and Tingley, 2014). Of particular importance for understanding isoGDGT-based proxies is that, at all temperatures, archaea must maintain semi-permeability without impacting rigidity (e.g., Chugunov et al., 2015). Most isoGDGTs involved in paleothermometry contain one or more cyclopentane rings, resulting in tighter packing and a more stable membrane (see Figure 1 in Zhou et al., 2020). At low temperatures, archaea reduce the number of cyclopentane rings in their membrane structures, thereby preventing membrane rigidity (Gabriel and Chong, 2000; Schouten et al., 2002). Indeed, Schouten et al. (2002) observed that the cyclization of isoGDGTs in surface marine sediments is correlated globally with measured surface water temperature in mesophilic (non-extreme) environments, resulting in the development of the first archaeal lipid paleothermometer, TEX86 (Table 1). In addition, in Thaumarchaeota, hydroxylation increases membrane fluidity and transport (Huguet et al., 2017), which compensates for increased rigidity at lower temperatures. The observation that the number of rings in hydroxylated isoGDGTs changes with temperature led to the development of ring-number-based OH-isoGDGT proxies (Fietz et al., 2013; Lü et al., 2015; Table 1).

Table 1. Isoprenoid and hydroxylated GDGT-derived indices proposed for paleotemperature estimates. In the equations, the abbreviation GDGTn represents isoGDGTs with n number of cyclopentane rings. For example, isoGDGT-1 represents the non-hydroxylated isoprenoid GDGT with one cyclopentane moiety. The abbreviation OH-isoGDGTn stands for hydroxylated isoprenoid GDGTs with n number of cyclopentane rings. The term ΣisoGDGTs refers to the sum of all non-hydroxylated isoprenoid GDGTs (e.g., isoGDGT-1, isoGDGT-2, isoGDGT-3, crenarchaeol and its isomer, abbreviated in this table as cren'). The term ΣOH-isoGDGTs refers to the sum of OH-isoGDGT-0, OH-isoGDGT-1 and OH-isoGDGT-2. > High res table

|

TEX86 Reconstructions in Polar Oceans: Opportunities and Challenges

The general relationship between the number of rings in sedimentary GDGTs and the overlying mean annual sea surface temperature is that the warmer the seawater, the more isoGDGTs there are with higher numbers of cyclopentane rings (e.g., isoGDGT-2 and isoGDGT-3), resulting in higher TEX86 index values; incorporation of the isomer of crenarchaeol adds accuracy (Sinninghe Damsté et al., 2002). Kim et al. (2010) proposed a variant of TEX86, termed TEXL86, that employs a different GDGT combination (TEXL86; Table 1) and is intended for temperatures below 15°C.

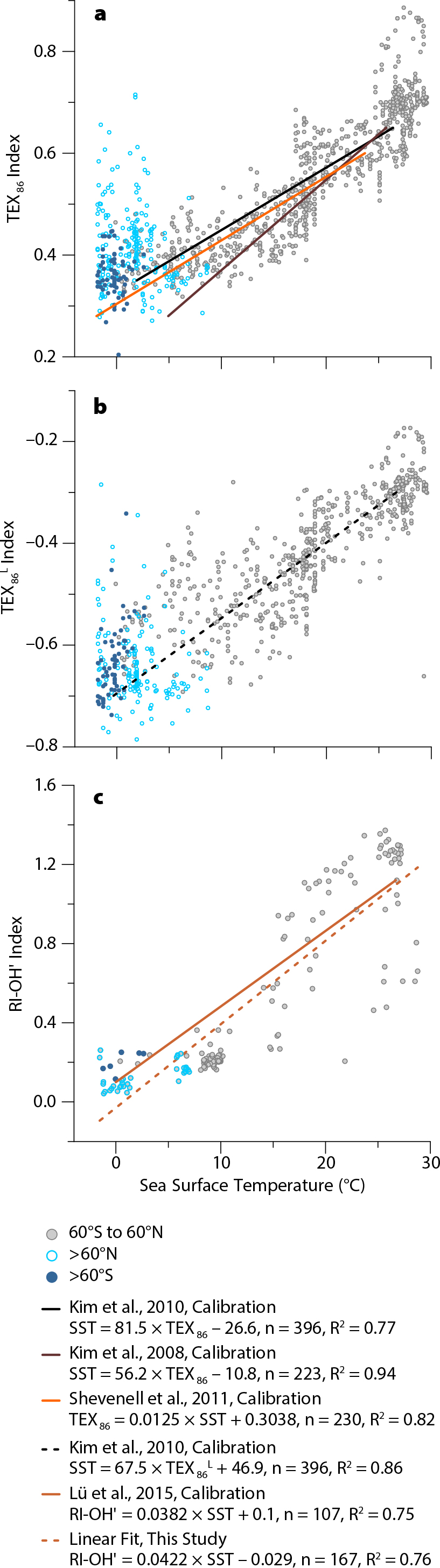

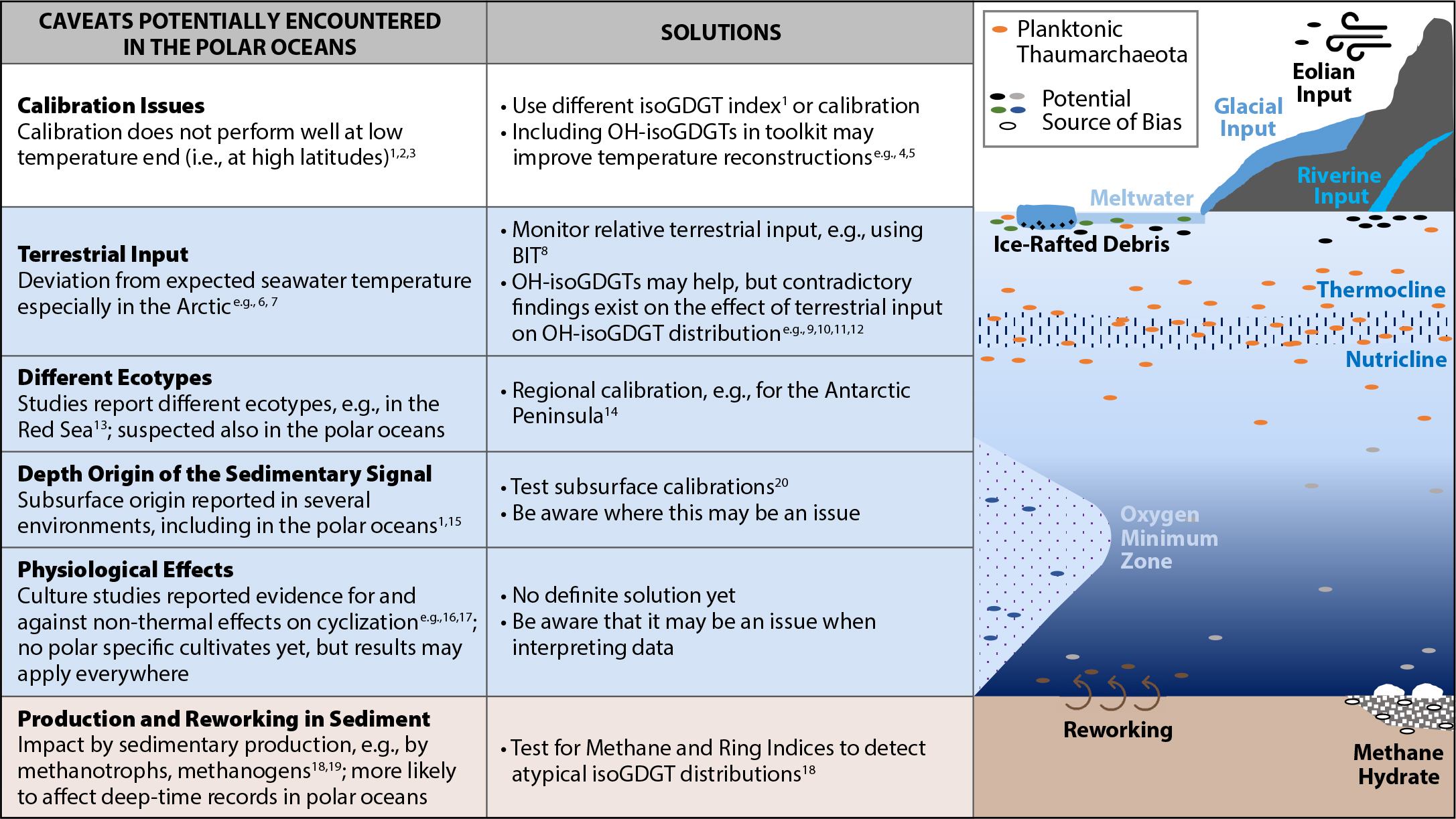

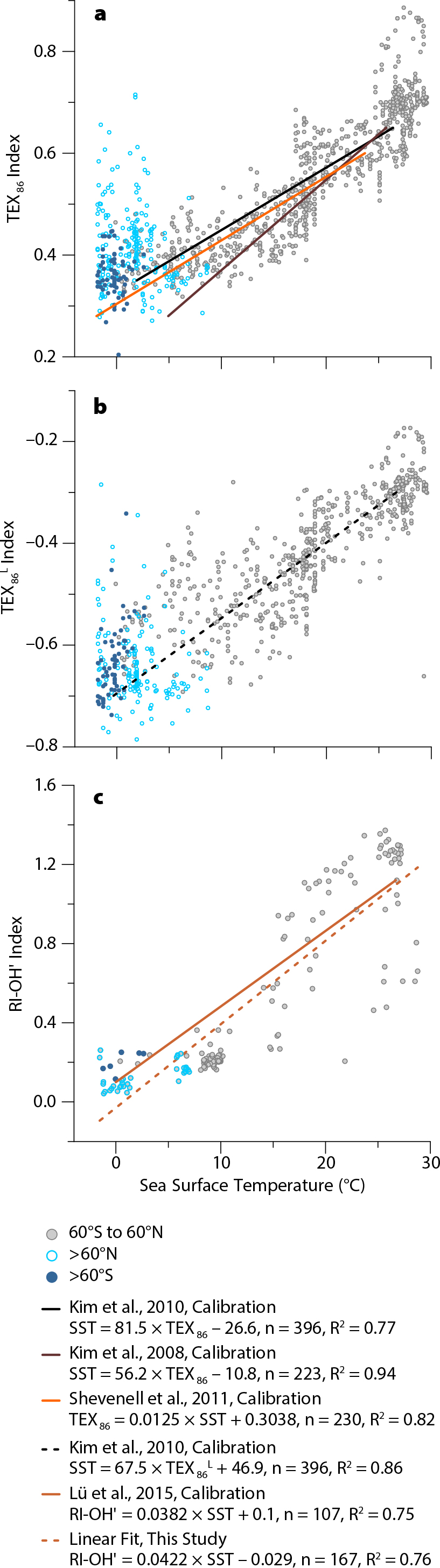

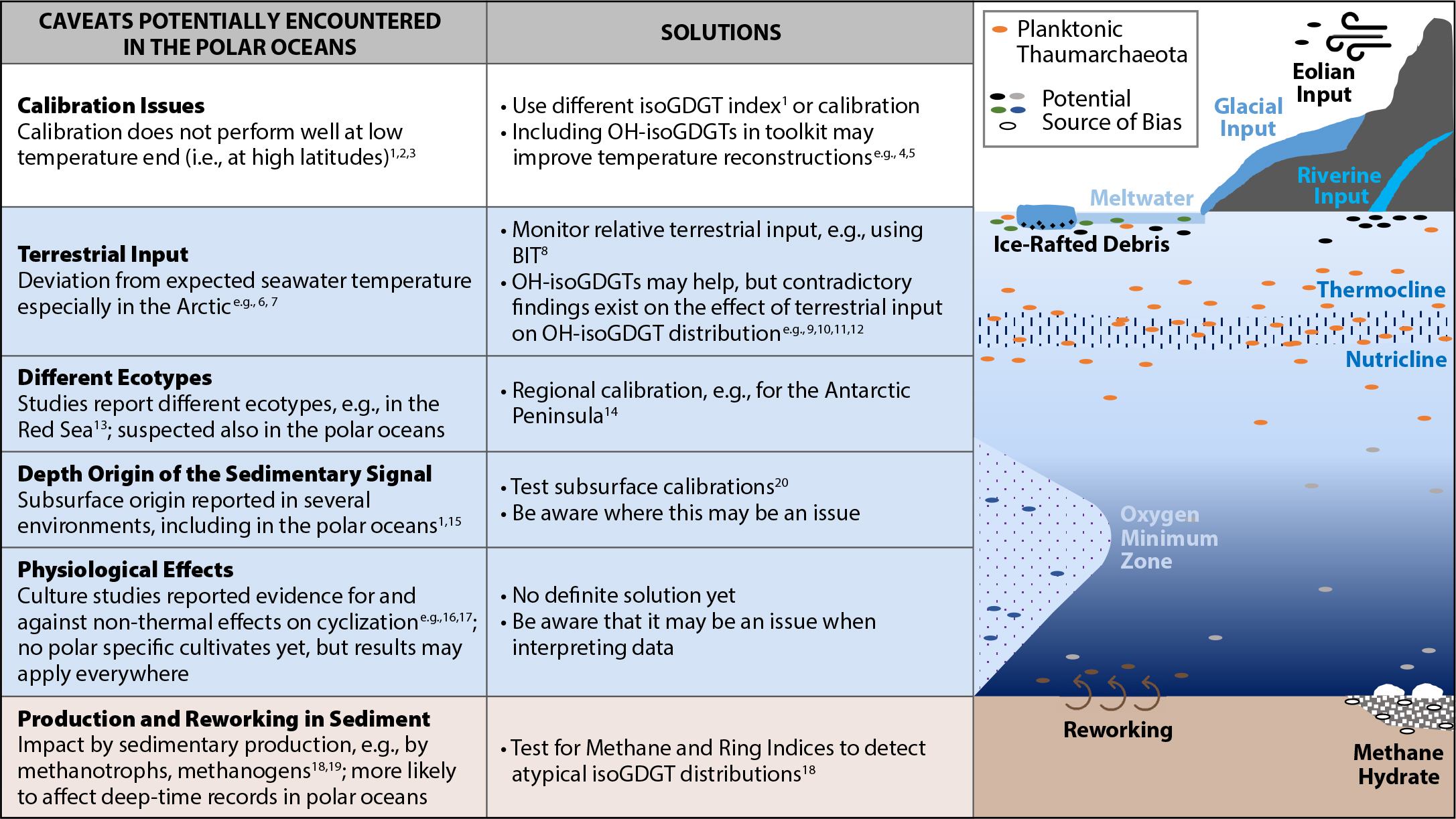

The isoGDGT-derived indices in surface sediments are generally well correlated with seawater temperatures in the overlying upper water column (e.g., Kim et al., 2010; Ho et al., 2014; Tierney and Tingley, 2014; Figure 1). In global calibrations, the standard errors of temperature estimates vary between 4.0°C and 5.2°C for TEXL86 and TEX86, respectively (Kim et al., 2010). Inter-laboratory error (3°–4°C) for TEX86 are the same order of magnitude as other commonly used quantitative temperature proxies (Schouten et al., 2013). There is, however, a larger scatter in the TEX86–sea surface temperature (SST) relationships at the low temperature end of the calibrations (Figure 1; Kim et al., 2010; Ho et al., 2014; Tierney and Tingley, 2014). The scatter is partly due to bias from terrestrial input, especially in the Arctic Ocean (Ho et al., 2014; Y. Park et al., 2014), and potentially from the use of satellite-assigned sea surface temperatures below the seawater freezing point for some calibrations (Pearson and Ingalls, 2013). Large scatter in TEX86–SST relationship is not an issue unique to the polar oceans. It also exists at the high-temperature end in the Red Sea (Figure 1), likely due to an endemic Thaumarchaeota population (Trommer et al., 2009). As such, TEX86 and its variants may be affected by environmental conditions other than temperature, such as pH (Elling et al., 2015), oxygen availability (Qin et al., 2015), cellular physiological acclimation including ammonia oxidation rates (Elling et al., 2014; Hurley et al., 2016), and shifts in season and depth of production (Huguet et al., 2007; Ho and Laepple, 2016; Chen et al., 2018). Many of the caveats mentioned above have been reviewed for the global ocean in general (see, for example, comprehensive reviews by Pearson and Ingalls, 2013; Schouten et al., 2013; and Tierney, 2014). Figure 2 illustrates concerns raised for the polar oceans.

Figure 1. Selected global calibrations for paleothermometers (a) TEX86 (TetraEther indeX of 86 carbons), (b) TEXL86 (which employs a different combination of glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers from TEX86 and is intended for temperatures below 15°C), and (c) RI-OH' (the weighted average number of cyclopentane rings) against sea surface temperatures. The data for the scatterplots in (a) and (b) are sourced from Tierney and Tingley (2015). A new, extended compilation of published data sets is presented here for RI-OH' (Fietz et al., 2013; Huguet et al., 2013; Lü et al., 2015; Kaiser and Arz, 2016). In (c), linear plots illustrate published calibrations for all three indices as well as a new linear fit for the extended RI-OH' data set. > High res figure

|

A solution for overcoming some of the caveats is to develop a regional calibration. For instance, Shevenell et al. (2011) applied a regionally calibrated TEX86 equation instead of TEXL86 to reconstruct Holocene temperature evolution in the Antarctic Peninsula (Figure 1a). Some sources of uncertainty, such as spatial change in the archaeal community, cannot be included in ordinary least squares regression approaches for global calibration. Thus, alternative statistical approaches have also been adopted to improve correlation of TEX86 with upper ocean temperature, such as Bayesian regression (BAYSPAR; Tierney and Tingley, 2014) and machine-learning approaches (OPTiMAL; Eley et al., 2019).

Figure 2. Overview of processes in the water column that can bias the isoprenoidal glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether (isoGDGT)-based paleotemperature reconstruction, especially in the polar oceans. Recommendations on how to work with such caveats and how including hydroxylated isoGDGTs (OH-isoGDGTs) in the paleothermometry toolbox may help are included. 1Kim et al. (2010), 2Ho et al. (2014), 3Tierney and Tingley (2014), 4Fietz et al. (2013), 5Fietz et al. (2016), 6Ho et al. (2014), 7Y. Park et al. (2014), 8Hopmans et al. (2004), 9Kaiser and Arz (2016), 10Lü et al. (2019), 11Kang et al. (2017), 12Wei et al. (2019), 13Ionescu et al. (2009), 14Shevenell et al. (2011), 15Huguet et al. (2007), 16Wuchter et al. (2004), 17Qin et al. (2015), 18Zhang et al. (2016), 19Shah et al. (2008), 20Ho and Laepple (2016). > High res figure

|

|

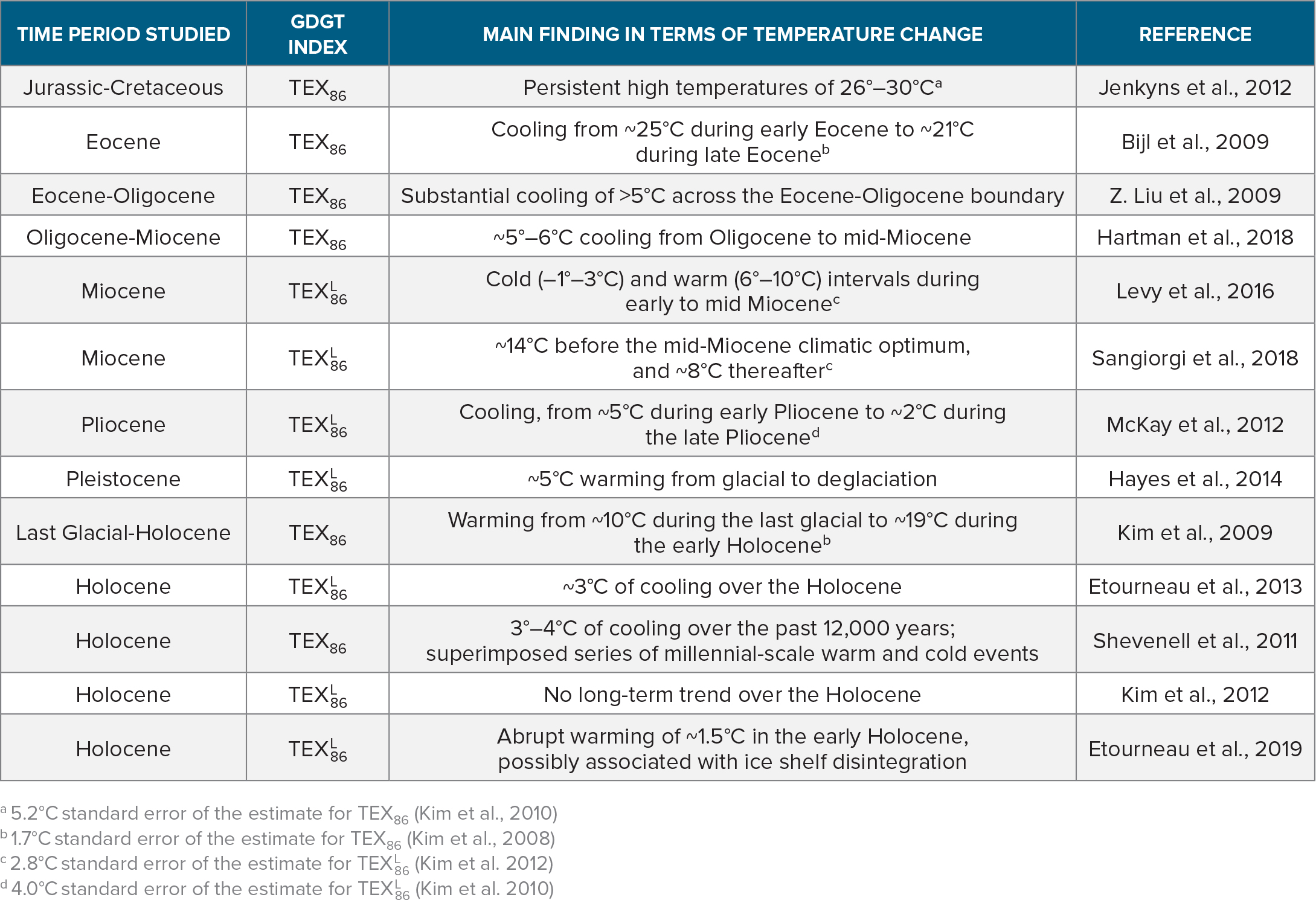

Despite calibration challenges, inherent to all paleotemperature proxies, the TEX86 paleothermometer revolutionized understanding of past ocean temperature changes in the carbonate-poor polar regions. In the Arctic Ocean, TEX86 provided one of the first quantitative temperature estimates for past warm climates characterized by high atmospheric CO2, such as the Cretaceous and the Eocene. TEX86 revealed that the Arctic surface ocean during these time periods was as warm as today’s subtropics, a stark contrast to the currently ice-covered Arctic (e.g., Jenkyns et al., 2004; Brinkhuis et al., 2006; Sluijs et al., 2006). Similarly, in the Southern Ocean, TEX86 and its variants have made it possible to reconstruct the temperature evolution from the Jurassic to the Holocene (summarized in Table 2). Thanks to this large body of work, we now know that the surface temperature of the Southern Ocean was once as high as 30°C during the Jurassic (Jenkyns et al., 2012) and has cooled through the Cenozoic, resulting in present-day temperatures surrounding the Antarctic Peninsula (Shevenell et al., 2011; Etourneau et al., 2013). Importantly, TEX86-based reconstructions have helped characterize past greenhouse climates, suggesting that Antarctic surface water temperatures were >10°C during the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (e.g., Bijl et al., 2009). These reconstructions also improved understanding of temperature magnitude ranges over major climate transitions, including the >4°C cooling across the Eocene-Oligocene transition (e.g., Bijl et al., 2009; Z. Liu et al., 2009). TEX86-based paleotemperature studies also indicate that in climatically sensitive regions, surface ocean temperatures fluctuated abruptly during the Holocene (Shevenell et al., 2011), suggesting the potential for rapid polar ocean temperature fluctuations with continued warming. Furthermore, both long-term cooling and millennial-scale variability on the western Antarctic Peninsula are similar to changes in the low latitudes (i.e., the tropical Pacific) and in regional ice core records (Mulvaney et al., 2012), suggesting climate teleconnections between the low and high latitudes via the Southern Hemisphere westerlies (Shevenell et al., 2011).

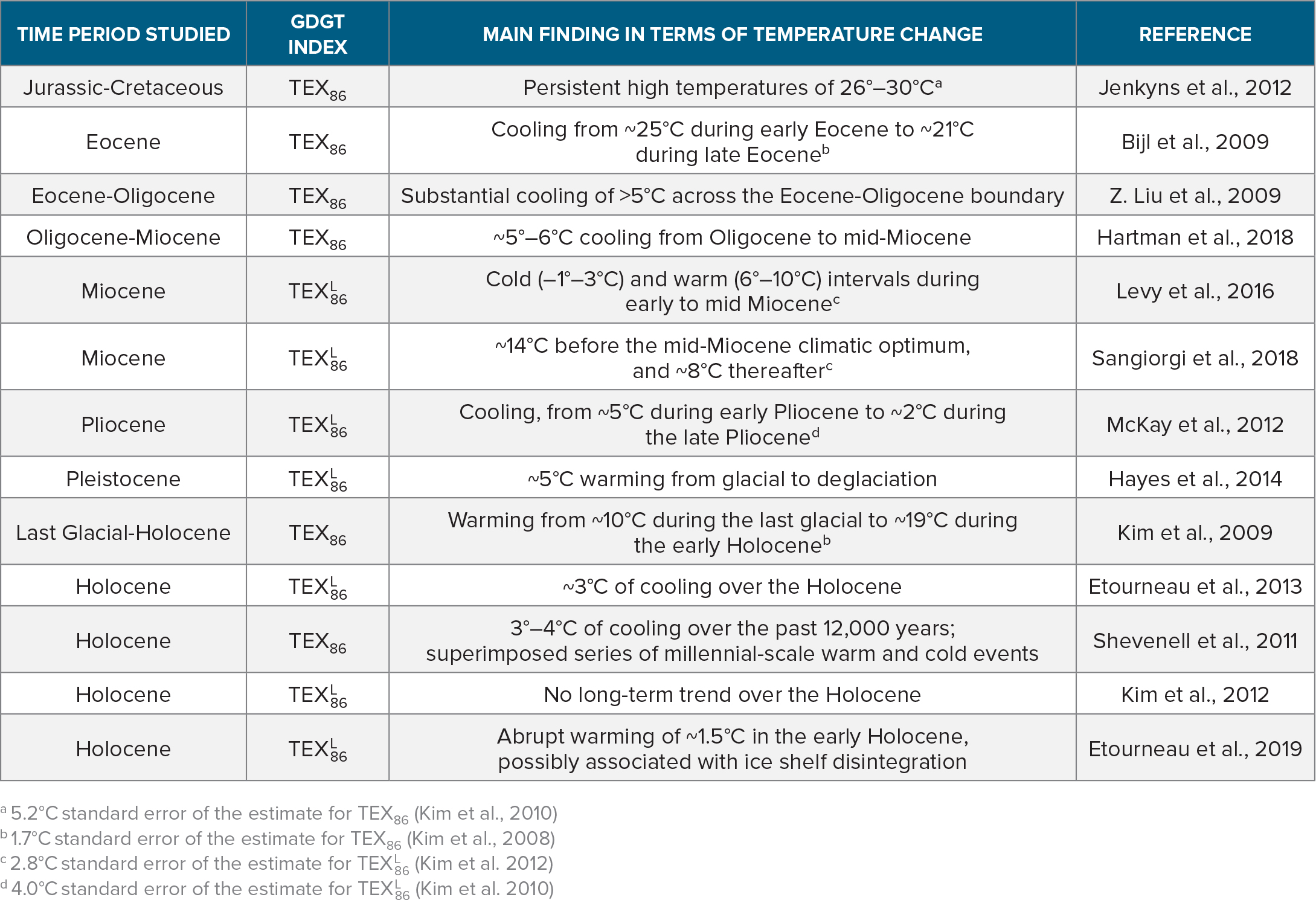

Table 2. isoGDGT-inferred Jurassic-Holocene upper ocean temperature evolution in the Southern Ocean. > High res table

|

Does Including OH-isoGDGTs in Temperature Proxy Index Improve the Estimates?

At some sites in the Arctic and Southern Oceans, TEX86 and TEXL86 do not show expected changes. For example, analyses using these proxies do not reflect the warmer conditions during glacial retreat in the Pliocene Arctic (Knies et al., 2014), during the Plio-Pleistocene transition and Pleistocene deglaciations in the Southern Ocean (e.g., McKay et al., 2012; Fietz et al., 2016), and during the late Holocene Arctic sea ice melting (e.g., Fietz et al., 2013). Some inconsistencies in warmer reconstructed temperatures during the deglacials compared to peak interglacials may be attributed to increased meltwater stratification (Shevenell et al., 2011; McKay et al., 2012). Another caveat of particular importance here is the potential lack of TEX86 sensitivity at temperatures below 10°C as observed in mesocosms studies (e.g., Wuchter et al., 2004). In cold waters, archaea adjust the permeability of their membranes by changing the number of rings and adding hydroxyl groups. Including only one of the processes in the proxy index may therefore underestimate the full range of temperature acclimations of archaea in polar oceans. Hence, accounting for both processes by adding OH-isoGDGTs to the paleothermometer index should, in principle, improve the sensitivity of the proxy.

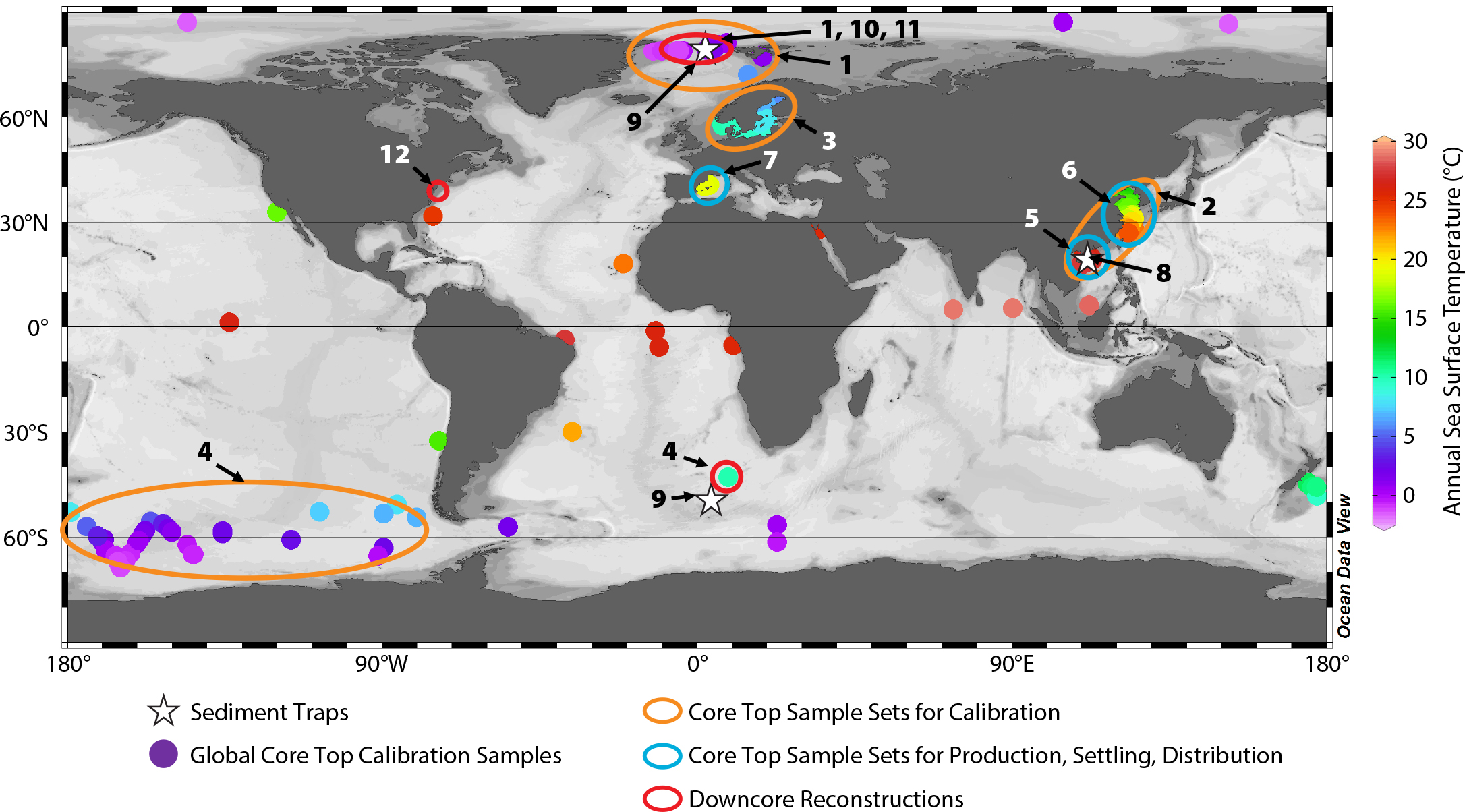

Like isoGDGTs, OH-isoGDGTs are globally distributed in the water column and in sediments (X.-L. Liu et al., 2012; Huguet et al., 2013; Figure 3). X.L. Liu et al. (2012) suggested that OH-isoGDGTs had potential for paleothermometry, and Huguet et al. (2013) proposed the first OH-isoGDGTs-based temperature proxy after observing a strong correlation between the relative abundance of OH-isoGDGTs and sea surface temperatures in globally distributed seawater and sediment samples. Thereafter, several indices were proposed for applications in the polar oceans (Table 1). While the addition of hydroxylated isoGDGTs in the isoGDGT toolbox was originally proposed as an alternative for cold water paleothermometry (e.g., Fietz et al., 2013; Huguet et al., 2013), it was later suggested that an OH-isoGDGT-temperature relationship also exists globally (Lü et al., 2015). The finding of OH-isoGDGTs in a large set of surface sediments in Chinese coastal seas (n = 70; Figure 3) led Lü et al. (2015) to propose the weighted average number of cyclopentane rings (RI-OH index) as a proxy for sea surface temperatures, as well as a polar variant, the RI-OH' (Table 1; Figure 1c), with a residual standard error of 6.0°C (compared to 5.2°C for TEX86; Kim et al., 2010). This RI-OH index reasonably reproduced TEX86-derived temperatures dating back 30–40 million years for the US New Jersey shelf (de Bar et al., 2019).

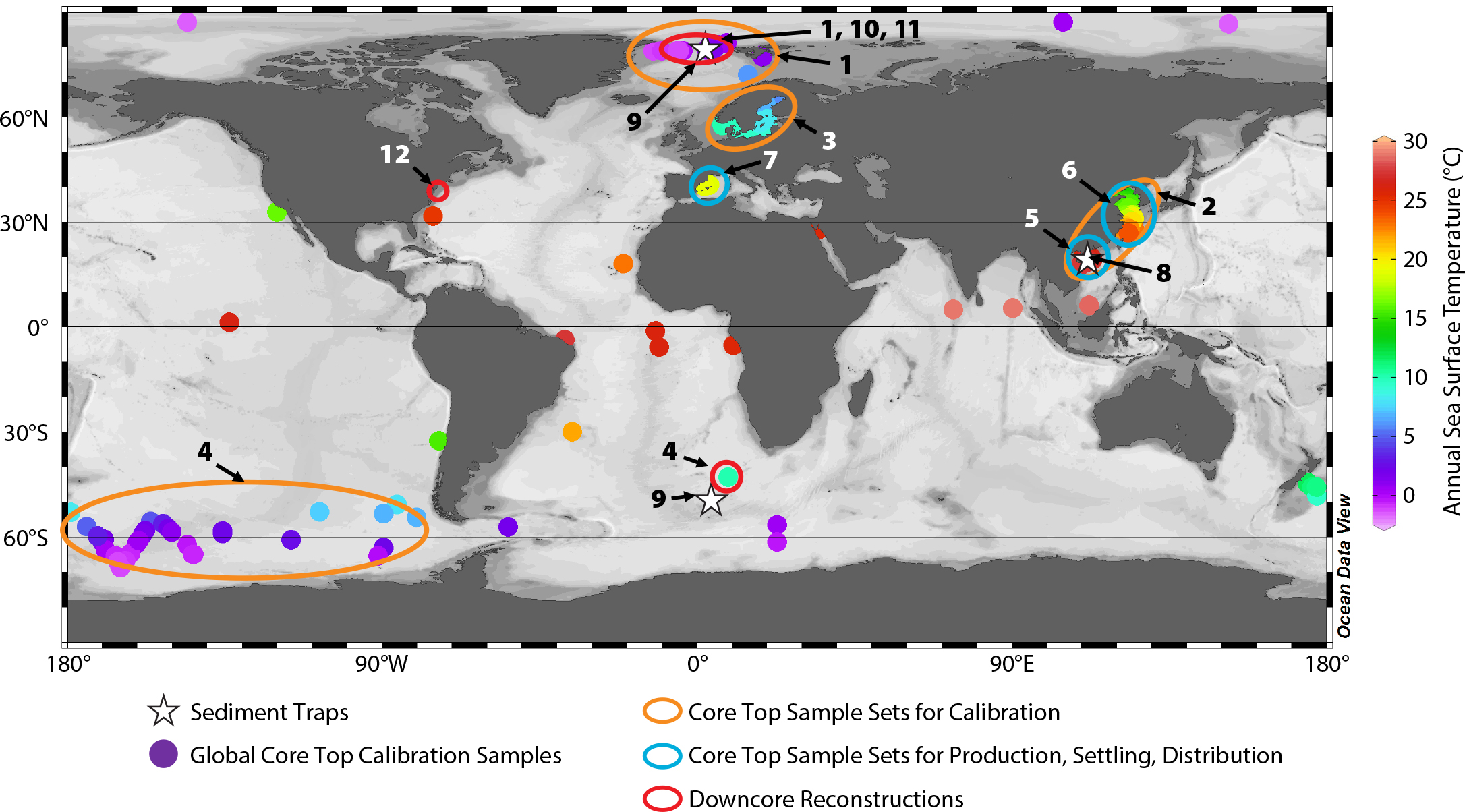

Figure 3. An Ocean Data View (Schlitzer, 2018) map illustrates the progress made since the OH-isoGDGTs were first proposed in 2013 as paleotemperature proxies, including surface sediment sample locations used for calibrations of initial OH-isoGDGT% (unlabeled filled circles; Huguet et al., 2013). Orange circles roughly indicate the locations of the additional sample sets for calibrations of cyclization variants, such as OH-isoGDGT1318/1316 (Table 1) by Fietz et al. (2013, #1), RI-OH and RI-OH' (Table 1) by Lü et al. (2015; #2), and improved calibrations thereof by Kaiser and Arz (2016; #3), as well as for OHc index determination (Table 1) by Fietz et al. (2016; #4). Blue circles highlight focus areas of surface sediment studies that improve our understanding of OH-isoGDGT production, settling, and thus ultimately, distribution in the sediment (#5, Lü et al., 2019; #6, Kang et al., 2017; #7, Davtian et al., 2019). White stars indicate two sediment trap studies (#8, Wei et al., 2019, South China Sea; #9, E. Park et al., 2019, Fram Strait and Southern Ocean). Red circles roughly indicate downcore temperature reconstructions (#1, Fietz et al., 2013; #10, Knies et al., 2014; #4, Fietz et al., 2016; #11, Kremer et al., 2018; #12, de Bar et al., 2019). Circles and stars are not to scale and may not represent 100% of the data set. > High res figure

|

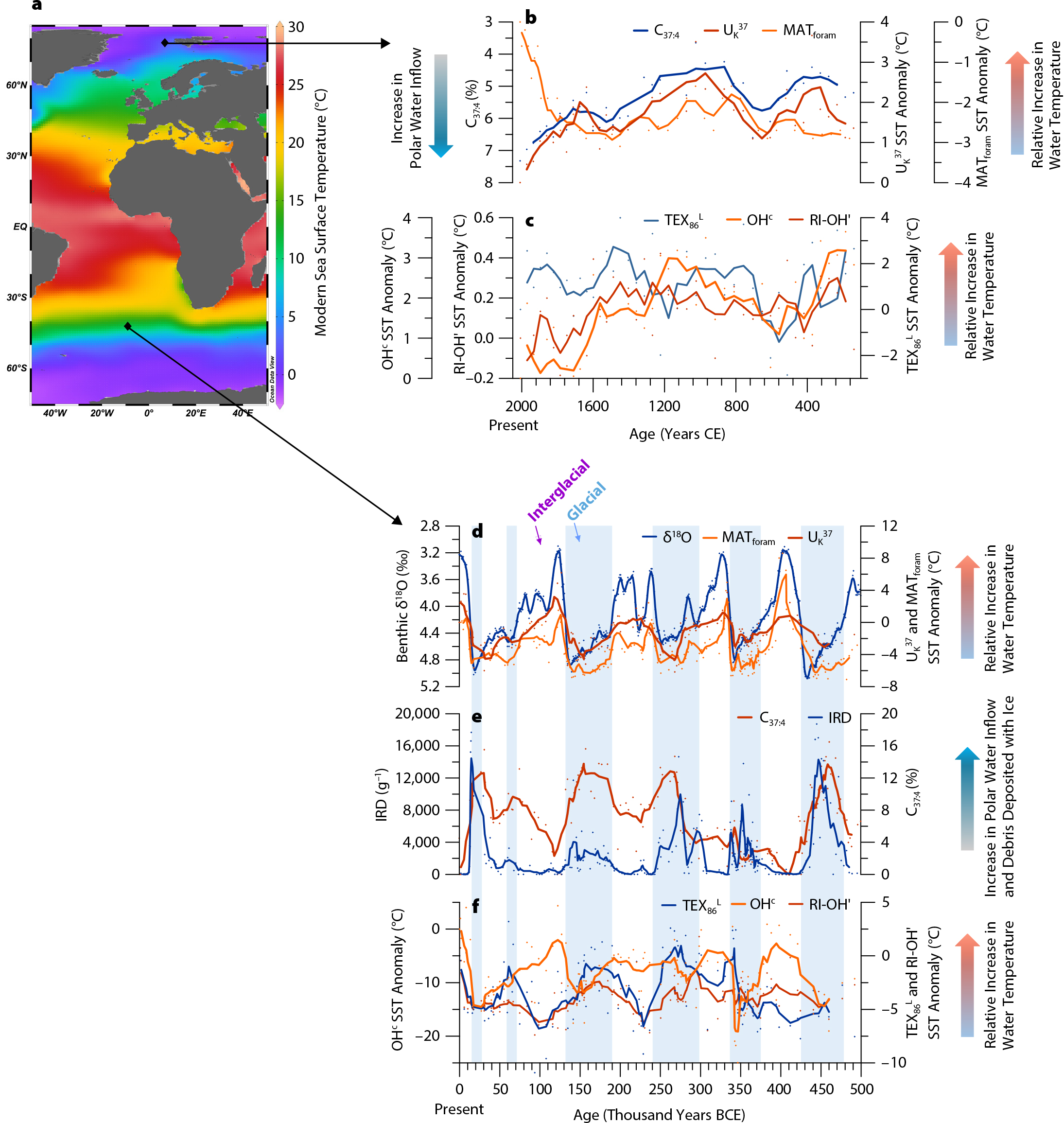

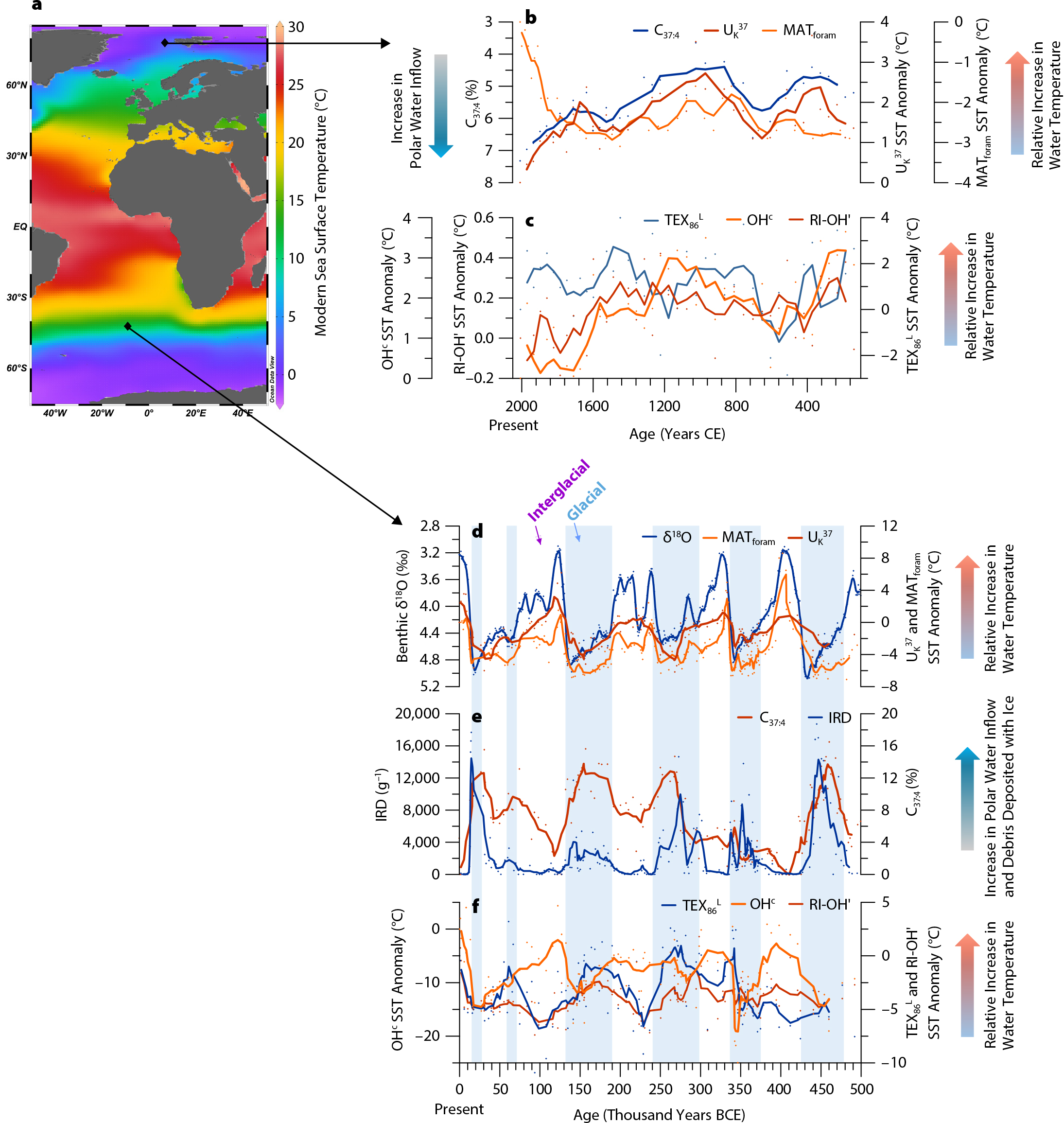

Thus far, OH-isoGDGT-based proxies have been applied to Arctic and Southern Ocean sediments to reconstruct seawater temperatures and to help elucidate ice-ocean dynamics (Fietz et al., 2013, 2016; Knies et al., 2014; Kremer et al., 2018). In these cases, OH-isoGDGT proxies were utilized instead of TEX86 as the latter did not yield changes in accordance with other proxies (Figure 4). For example, in Fram Strait, the gateway to the Arctic Ocean, the OH-isoGDGT-derived indices indicated sea surface cooling of ~5°C (OH-isoGDGT%) and ~3°C (RI-OH') across the Plio-Pleistocene transition, suggesting an increasing influence of polar water masses (Knies et al., 2014). In contrast, TEXL86 temperatures did not reveal consistent temporal patterns. Meanwhile, a reconstruction over the past ~120,000 years (Kremer et al., 2018) revealed more reasonable RI-OH'-inferred temperatures (–2.5° to 2.5°C; calibration error of 6°C) than TEXL86-derived temperatures (–17° to 9°C; calibration error of 4°C). Over the Holocene, temperatures based on the OH-isoGDGT% and RI-OH' indices also followed trends in temperature and water mass changes indicated by multiple proxies, in contrast to the TEXL86-based temperatures (Fietz et al., 2013; Figure 4).

The reasons for the mismatch between TEX86-related temperatures and other proxies in the Arctic are unknown. The isoGDGT-based Ring Index (Zhang et al., 2016) may shed light on the extent of non-thermal bias of the TEX86-related reconstructions, especially potential terrestrial input. Ring Index offset values lower than 0.3 at the Plio-Pleistocene transition (Knies et al., 2014) and in the Holocene (Fietz et al., 2013) do not point to a specific non-thermal bias. The factors driving the mismatch between TEX86-related temperatures and other proxies in the Arctic do not seem to affect the utility of OH-isoGDGT proxies, as the reconstruction based on them coevolves with other temperature proxies (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Multi-proxy based reconstructions of sea surface temperature and related parameters in the polar oceans. (a) Modern annual mean sea surface temperatures (from WOA2013, Locarnini et al., 2013). Black diamonds indicate the two sediment core sites in the Arctic (b–c) and Atlantic Southern Ocean (d–f). (b) Relative abundance of C37:4 alkenones and UK37 sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies (Rueda et al., 2013) as well as SST anomalies reconstructed using modern analogue technique (MATforam-SST, Spielhagen et al., 2011). (c) TEX86-, TEXL86-, and RI-OH'-derived SST anomalies using calibrations in Kim et al. (2010) and Lü et al. (2015), as well as OHc-derived SST using calibration in Fietz et al. (2016). (d) Benthic δ18O stack (Lisiecki and Raymo, 2005), summer SST (SSST) anomalies reconstructed using the modern analogue technique (MATforam-SSST; Becquey and Gersonde, 2002) and UK37 SST anomalies (Martinez-Garcia et al., 2009). (e) Relative abundance of C37:4 alkenones to total C37 alkenones, indicating cold water mass influence (Martinez-Garcia et al., 2009) and ice rafted debris (IRD) concentration (Becquey and Gersonde, 2002). (f) TEX86- and RI-OH'-derived SST anomalies using calibrations in Kim et al. (2010) and Lü et al. (2015) as well as OHc-derived SST (Fietz et al., 2016). Data and graphs (b–c) adapted from Fietz et al. (2013). Data and graphs (d–f) adapted from Fietz et al. (2016). Blue shaded bars in (d–f) denote glacial stages. All index equations are provided in Table 1. All anomalies refer to the core top value as “0.” > High res figure

|

The OH-isoGDGT proxy has not been widely tested in the Southern Ocean. E. Park et al. (2019) recently published the very first sediment trap-based study indicating that several OH-isoGDGT-based proxies show promise as temperature proxies for both the Arctic and the Southern Oceans. To date, only one study has applied the OH-isoGDGTs for reconstructions in the Southern Ocean (Fietz et al., 2016). Here, in the subantarctic Atlantic, TEX86 (Figure 3) suggests warmer conditions during glacials than interglacials in the past 500,000 years, in contrast to other paleotemperature proxies based on the same sediment core (Fietz et al., 2016). Located north of the winter sea ice extent during the last glacial maximum, some inconsistencies of warmer reconstructed temperatures during the glacial and colder temperatures during the interglacial may be attributed to increased meltwater stratification (Shevenell et al., 2011; McKay et al., 2012). Another possible explanation for the “warm” glacial TEX86-temperatures in the subantarctic Atlantic record could be the bias toward warmer TEX86-temperatures caused by low ammonium oxidizing rates (Hurley et al., 2016). However, higher eolian iron input during the glacials (Martinez-Garcia et al., 2009) would contribute to increased oxidation rates (Shafiee et al., 2019) and thus toward a cold bias of the TEX86 temperatures and vice versa in the interglacials. This is the opposite of the temporal patterns in the TEX86 records and, hence, a bias introduced by such nutrient dynamics does not explain the warm temperatures reconstructed during the glacials.

Adding OH-isoGDGTs in the temperature index improves the reconstruction to some degree. Unlike their counterparts TEX86 and TEXL86, the OH-isoGDGT indices exhibit temporal patterns that are more consistent with other non-isoGDGT-based proxies (Figure 4) and expectations (lower temperatures during glacials), with the OHc index showing the best match in the temporal trend. In the OHc index, the assumed cold-water end-member OH-isoGDGT-0 is subtracted from the numerator (Table 1). The fact that this approach improves the reconstruction of temperature evolution suggests that the addition of OH-isoGDGT in the temperature index may help to fully capture the temperature responses of archaeal membranes to temperature changes in polar waters. The global calibration of RI-OH (Lü et al., 2015) consists of 107 data points, a far cry from the TEX86 calibration data set (n >1,000; Tierney and Tingley, 2015). Here, we show that combining recently published surface sediment OH-isoGDGT data (n = 167; Figure 1c) does not change the global calibration equation nor the closeness of fit, but the database should be expanded to improve its robustness. Improvement of both the isoGDGT- and the OH-isoGDGT-based proxy calibrations remains a priority task for the future. As for TEX86, one approach is to develop more regional calibrations or use alternative statistical approaches, such as BAYSPAR (Tierney and Tingley, 2014) and OPTiMAL (Eley et al., 2019).

Nonetheless, some uncertainties remain. Even though OH-isoGDGTs have been found in cultured mesophilic Group I Thaumarchaeota and methanogenic Euryarchaeota (X.-L. Liu et al., 2012), and that OH-isoGDGTs have been proposed to be produced autochthonously in the marine water column (Lü et al., 2015; Kaiser and Arz, 2016; Lü et al., 2019; Davtian et al., 2019) and thus may circumvent the impact of terrestrial bias in TEX86-reconstructions (Figure 1), the possibility of terrestrial influence has recently been put forward (Kang et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2019). In addition, OH-isoGDGT proxies may also respond to environmental factors other than temperature, such as salinity, the presence of sea ice (Fietz et al., 2013), and/or seasonality (Lü et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2019). More ground truthing in water column and surface sediments, and most importantly culture incubation studies, are needed.

Conclusions

Over the last few decades, the TEX86 paleothermometer has been used to help reconstruct past changes in sea surface temperatures in the polar regions (e.g., Table 2). However, several caveats exist (Figure 2) and structurally different isoGDGTs have been identified, such as OH-isoGDGTs. More work is needed to shed light on these compounds and the proxies based on them, but a few preliminary studies show that incorporating OH-isoGDGTs in the temperature proxy index may lead to improved reconstructions in the polar oceans. We thus recommend that the OH-isoGDGTs be analyzed simultaneously during standard isoGDGTs analysis, as this multi-proxy approach will increase the robustness of paleotemperature reconstructions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous reviewers and guest editor Amelia Shevenell for the thorough review and valuable comments and suggestions. This work is based on the research supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa awarded to SF (#93072, #98905, #110731). CH wishes to acknowledge the Los Andes Faculty of Science INV-2019-84-1814 and the Humboldt Research Fellowship for Experienced Researchers. SLH acknowledges funding from the Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan; # 107-2611-M-002-021-MY3).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this article.