Full Text

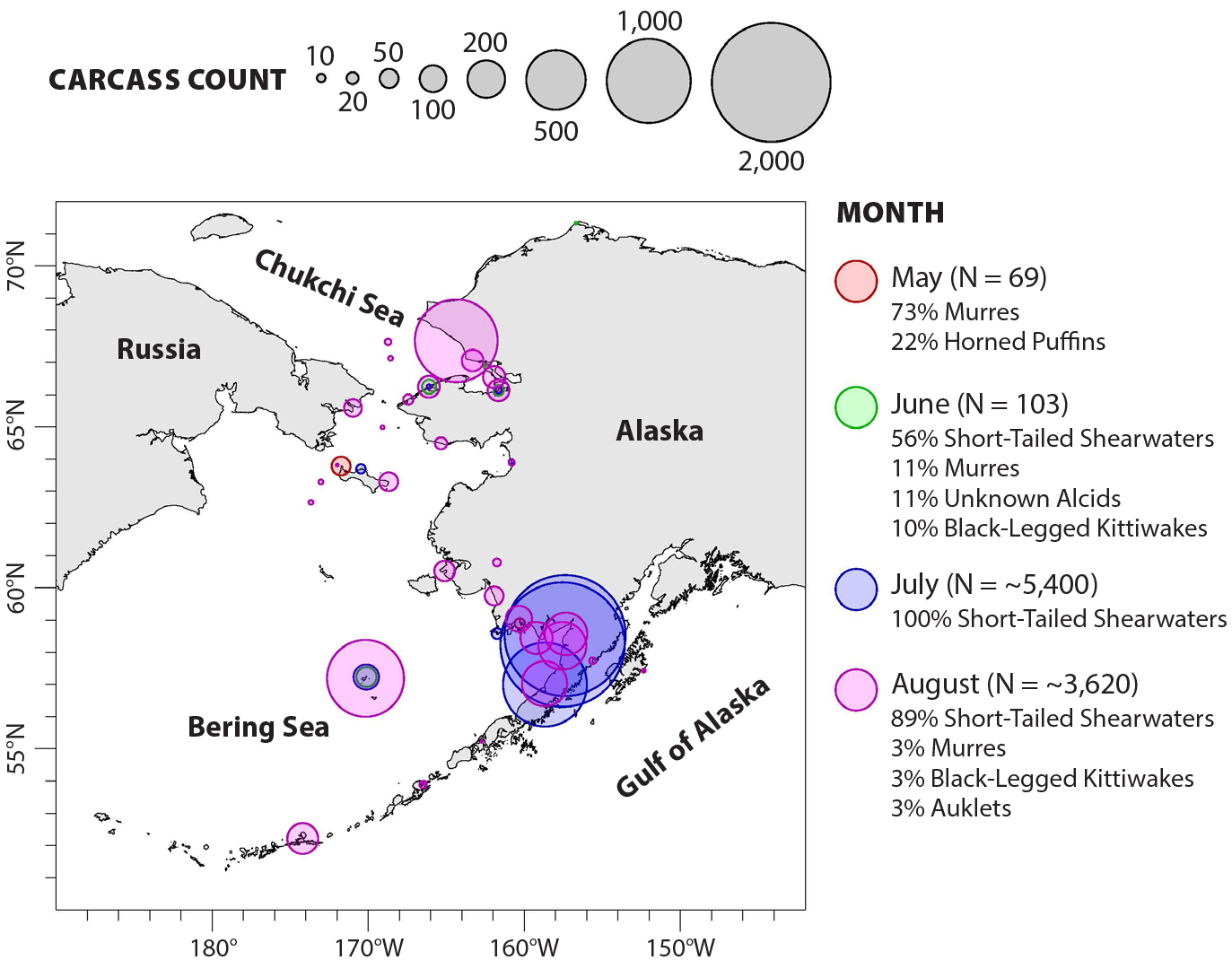

Prior to 2015, seabird die-offs in Alaskan waters (Northern Gulf of Alaska, eastern Bering Sea, eastern Chukchi Sea) were rare, typically occurred in mid-winter, and were linked to epizootic disease events (Bodenstein et al., 2015) or above-average ocean temperatures associated with strong El Niño-Southern Oscillation events. An example was late summer of 1997, a year with unusually warm waters in the southeastern Bering Sea, when possibly as many as 10% of the several million short-tailed shearwaters (Ardenna tenuitortris) present in the area died of starvation because their principal prey, euphausiids, were scarce or hard to find in a widespread coccolithophore bloom (Baduini et al., 2001). Since 2015, similar or smaller mass mortality events have been annual occurrences. In 2015, between 470,000 and 1.03 million common murres (Uria aalge) were estimated to have died in the Gulf of Alaska due to anomalous ocean conditions and the impacts on forage fish associated with the 2014–2016 Pacific marine heatwave (Piatt et al., 2020; Arimitsu et al., 2021). Another large die-off event occurred during late summer of 2019 (Figure 1), when over 10,000 carcasses of short-tailed shearwaters washed onto beaches of Bristol Bay and the Alaska Peninsula in the southeastern Bering Sea. Total mortality during that summer was likely much greater than reported given the region’s expansive coastline and sparse human population.

|

|

Seabirds are natural indicators of the status of marine ecosystems, and since at least 2017, die-offs in the northern Bering and southern Chukchi Seas (including some reports from the Russia Far East) have been concurrent with massive ecological shifts resulting from increased ocean temperatures coupled with decreased duration and extent of sea ice in those seas. Changes include a decrease in the large crustacean zooplankton that support planktivorous seabirds (Duffy-Anderson et al., 2019). In addition, there has been significant reduction of the cold pool thermal barrier, a layer of <2°C water near the seafloor that restricts species like Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus) and walleye pollock (Gadus chalcogrammus) from entering the northern Bering Sea. More recent studies in the Pacific Arctic region indicate the northward movement of adult cod and pollock (Duffy-Anderson et al., 2019; Eisner et al., 2020) that might compete with seabirds for food.

Seabird species affected since 2017 in eastern Bering and Chukchi Seas include planktivorous birds such as auklets (Aethia spp.) and shearwaters, piscivorous murres, puffins (Fratercula spp.), and kittiwakes (Rissa spp.), as well as some benthic-feeding sea ducks (Somateria spp.). Involvement of a range of seabird species that consume different prey, and localized mortality events throughout summer across a vast region (albeit with relatively low numbers at individual sites), signal broadscale, ecosystem-level impacts at multiple trophic levels. Such wildlife mortality events are of concern not only for coastal communities that rely on ocean resources for their nutritional, cultural, and economic well-being but also signal concern for the state of subarctic and Arctic oceans.

While starvation has been identified as the main cause of death for carcasses examined by US Geological Survey (USGS) National Wildlife Health Center scientists, university and federal researchers continue to evaluate other possible contributing factors. To date, highly pathogenic diseases have not been detected in tested carcasses. Exposure to saxitoxin, associated with harmful algal blooms, was detected in seabird tissues in 2017; however, direct neurotoxic results from saxitoxin could not be confirmed, and starvation appeared to be the proximate cause of death among birds examined (Van Hemert et al., 2021). USGS researchers at the Alaska Science Center continue to investigate algal toxins in marine invertebrates and forage fish and are conducting experimental trials to determine effects of saxitoxin on seabird behavior and health, which may include emaciation.

With seabird mortalities reported over a wide geographic region and throughout summer and fall on an annual basis, how are birds doing at breeding colonies? Observations at northern seabird breeding colonies indicate lack of breeding attempts or very late and unsuccessful breeding between 2017 and 2019 (Romano et al., 2020; Will et al., 2020). Although these observations suggest that the seabird die-offs stem from multiple ecosystem changes associated with abnormally high ocean temperatures, including forage fish quantity and quality, unfavorable foraging conditions (competition with fish), or exposure to harmful algal bloom biotoxins, there still is no confirmed “smoking gun.”

The bottom-up effects linked with changes in the prey base and top-down effects associated with increased metabolic rate, along with food demands of competing fish species that could reduce prey availability to seabirds and marine mammals, is referred to as an “ectothermic vise” by Piatt et al. (2020). With increasing ocean temperatures and decreasing sea ice, the next decade will be critical for upper trophic organisms and human communities adapting to a fast-changing environment in northern Alaska.