Full Text

[The bingo activity] made the cruise more fun and productive, because it made me pursue tasks and conversations that I would not have engaged in without the bingo, and I learned a good amount of new things.

– A student in our field course, 2023

In geosciences, fieldwork is a traditional way to teach various applications of disciplinary knowledge and practical skills and to introduce students to the scientific method (Malm, 2021). Many students are excited to join fieldwork and find it motivating and relevant for their future careers. In post-fieldwork surveys, our students at the Geophysical Institute, University of Bergen, Norway, typically describe their fieldwork using words such as instructive, exciting, fun, interesting, good experience, cooperation. The dominant discourse among geoscience teachers is also that “‘fieldwork is good’ for both social and academic purposes” (Malm, 2021). However, for various reasons, not all students take advantage of all opportunities within the scope of the fieldwork. For many students, there is a wide gap between what they learn through participation in a field course and what they need to be able to do later in more independent fieldwork.

Orion and Hofstein (1994) suggest that the educational effectiveness of fieldwork depends on both the fieldwork’s quality—the structure and quality of teaching—and the students’ familiarity with the fieldwork setting, which they refer to as “novelty space.” Fieldwork in geoscience usually takes place outdoors (in our case on research ships) and often requires a lot of previous experience to be comfortable and successful (e.g., knowing how to dress according to weather, hike in difficult terrain, lift heavy equipment, use manuals to operate scientific instruments). When students become overwhelmed with such practical issues, it takes focus and energy away from learning disciplinary knowledge and skills (Orion and Hofstein, 1994). Unfortunately, there is also a long history of propagating stereotypes of what a “successful geoscientist” looks like (“checkered button-down shirts and a beard,” as we have heard colleagues say to first-year students). This culture makes it harder for some students to feel that they belong (Malm, 2021), and we know that experiences of positive relationships are important for student learning (Felten and Lambert, 2020).

We want all our students to be able to make the most of the valuable learning opportunities that fieldwork presents, and for that purpose, we created gamified activity prompts. Those prompts encourage students toward seeing, seizing, and even creating opportunities for themselves—they “nudge” students to change their behavior in a desirable way without forcing them or punishing non-compliance (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). In the following, we describe our design process and our students’ experiences with our “fieldwork bingo” activity.

Creating a Fieldwork Bingo Activity

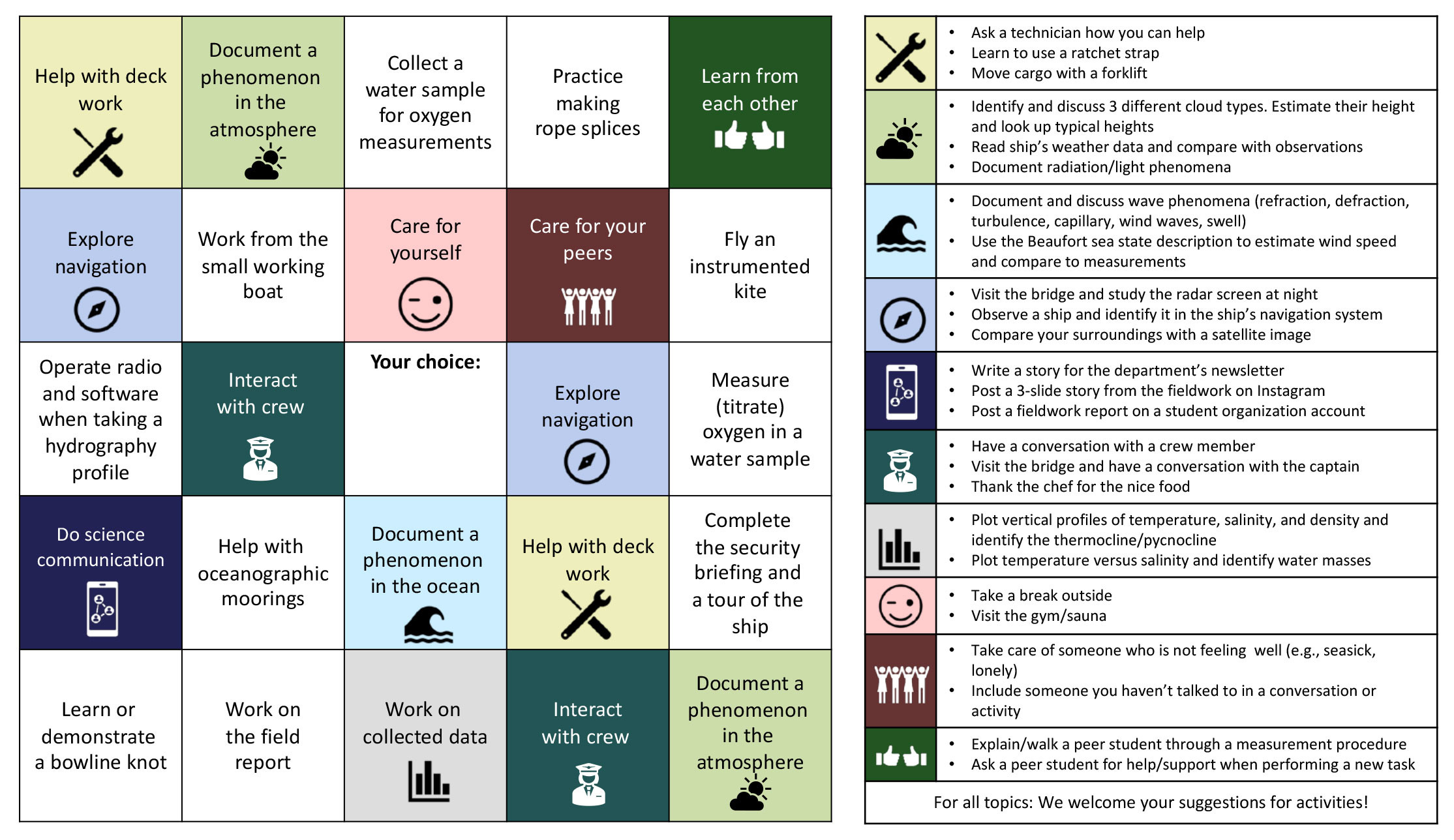

We use the layout of a bingo card to present a wide range of learning activities that we want to encourage students to engage in during the fieldwork. Filling out a bingo card is more appealing than working through a checklist, and most students intuitively know how to play bingo and feel drawn to checking boxes to complete a full row, column, or diagonal. In addition, strategic placement of activity prompts lets us subtly guide students toward certain activities. For example, some squares are replicated on the card more than others, providing additional opportunities to engage in those activities to get to bingo. Figure 1 shows an example of a fieldwork bingo card for a four-day student cruise on a research ship.

|

|

Identifying Intended Learning Outcomes and Choosing Activities

To create a bingo card, we first collect and discuss intended learning outcomes with all teachers and teaching assistants involved in the course. It is fairly easy to identify learning outcomes and activities relevant to the curriculum that we want to encourage students to engage in during their time on board. Such activities might not be explicitly mentioned in the curriculum, for example, handling specific equipment, taking distinct measurements, and documenting the experience for future reports, but they are typically the reason why we go into the field in the first place. Many students will readily engage in them, but some need the extra prompt. This is especially true on cruises with large numbers of students, where only a few students at a time can perform a specific task. Ensuring that everyone participates in a variety of activities can become challenging because of the difficulty of tracking individual contributions. Fieldwork bingo can increase the probability that every student engages in a basic set of tasks, facilitating a comprehensive experience for all.

Good indicators of the less obvious activities that might be useful to include in a bingo card are recollections of situations where we noticed some students (or sometimes even instructors) eagerly creating interesting and beneficial learning opportunities for themselves (or ourselves) that did not appear to interest other students. Some ideas come from conversations with other people involved in the fieldwork, for example, the crew on a research ship. We reflect on what useful learning students may miss out on if we do not encourage them explicitly (e.g., related to the “etiquette” on a research ship; Glessmer, 2019), and create corresponding activity prompts.

Placing Activities on the Bingo Cards

We then categorize and prioritize activities. Some activities we deem so important that we want to include them explicitly in their own fields, for example, “collect a water sample for oxygen measurements.” We also offer the opportunity for each student to choose activities that have personal relevance for them by including umbrella categories. There, students choose from a list or suggest their own activities that are relevant in that category. For umbrella categories, it is more important that students think about the category in general than what they actually do. Such categories include practical work, social interactions with peers and crew members, and connecting theoretical disciplinary knowledge to observations of the real world.

We leave the center square empty to allow students to freely suggest their own activities. These “choice” fields encourage students to actively think about what other activities or experiences they might benefit from and want to seek out, to better connect different tasks with disciplinary content, to expand their horizons, and to take ownership of their learning. The students did take the “free choice” option seriously and chose tasks that were meaningful to them and deserved highlighting, both for themselves and for the teacher. The “free choice” tasks roughly fell into three categories: taking responsibility for “household chores” (e.g., “tidying up the mess in the water samples”), learning useful skills (e.g., soldering), or science communication (e.g., documenting the work for the institute’s newsletter). Finally, we also include some low-threshold activities on the bingo card (e.g., participation in the security briefing, which is mandatory for all students anyway) to get students started.

To construct the bingo card, we created a table in PowerPoint and coded both the table and list of suggested activities for accessibility with a color-blind friendly palette (Tol, 2021) as well as with icons. An editable PowerPoint document of the bingo card shown in Figure 1 can be downloaded at https://cocreatinggfi.w.uib.no/bingo.

Supporting Student Motivation

Playing fieldwork bingo is a voluntary activity for our students. Including competition and prizes might seem fitting with the playful approach of bingo, but rewards should be used with caution, as they can also undermine intrinsic motivation (Kohn, 1994). In our case, all those who completed their first bingo patterns were given an inexpensive neckwarmer. We did observe students trying to finish their first bingo row in order to get a neckwarmer, which is of practical use on a cruise (to wear under a helmet). However, none of the students mentioned them as the reason they were motivated to engage with the activity. So even though the small reward seemed to be appreciated, it did not appear to have a big influence on the students’ perception of the bingo.

Rather than relying on incentives to encourage engagement, we designed our bingo card to address the three components of self-determination theory that support intrinsic motivation: relatedness, competence, and autonomy (Deci and Ryan, 2000). This means we designed the activities in such a way that students were likely to experience connection and meaningful interaction with peers, teachers, and others; that they felt capable of mastering new challenges; and that they felt they had choice in what to do, when to do it, and with whom to do it. In free-text feedback after the cruise, students highlighted aspects of all three components as especially positive, and reported that the bingo did indeed contribute to their motivation and engagement with the unique learning opportunities of the research cruise (see Box 1).

|

Considerations for Future Bingo Activities

Complementing what the students reported after the cruise, we observed a lot of positive interactions between students and staff, students’ active engagement and success in carrying out unfamiliar tasks, and their use of the time on board to explore many different aspects of this unique opportunity. In particular, interactions with the research ship’s crew were highlighted as positive experiences that were both unexpected and educational. Students were unaware that the crew typically welcomes conversations with students, but student-crew interactions resulted in the students being taught practical skills that turned out to be directly useful both on the cruise and in later fieldwork. We conclude that the bingo activity served its purpose, and we are thinking about how to use and improve it going forward.

We adapt the bingo cards specifically for each instance we use them, not just in terms of the intended learning outcomes of a course, but also depending on the context of the course. For example, if students do not know each other well before the fieldwork, they benefit especially from activities that provide them with opportunities to socialize and get to know each other. Similarly, if the student group is very diverse in terms of prior experience, including competition might discourage less experienced students from engaging.

Before, during, and after this experience, we have had many interesting discussions with other teachers and students who see the potential of using a bingo approach in their teaching and learning contexts. For example, one of the experienced students participating in our cruise will be teaching a field course later this year and writes: “The bingo helped me in understanding a bit better what motivates students to get engaged in more activities, and how to make learning feel more ‘voluntary’ and entertaining. I am currently thinking of making a different version for the students of our cruise in September.”

Now that you have seen what we do and how we and our students think about it, we are curious to hear your thoughts! How would you use such a bingo activity in your context? What suggestions do you have for improving our bingo activity? Please reach out!