Unpacking Diversity: A Professional Learning Community

Founded in 2016, Unpacking Diversity: A Professional Learning Community (hereafter, “Unpacking Diversity”) was a graduate student-led grassroots effort focused on diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice (DEIJ) issues within a geoscience college. This initiative pursued equitable outcomes and increased awareness of the marginalization experienced by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) within our interdisciplinary geoscience college at a public, predominantly white institution (PWI) that provides essential training and research opportunities to future scholars in the disciplines of ocean sciences, marine resources, geology/geophysics, geography, and environmental sciences.

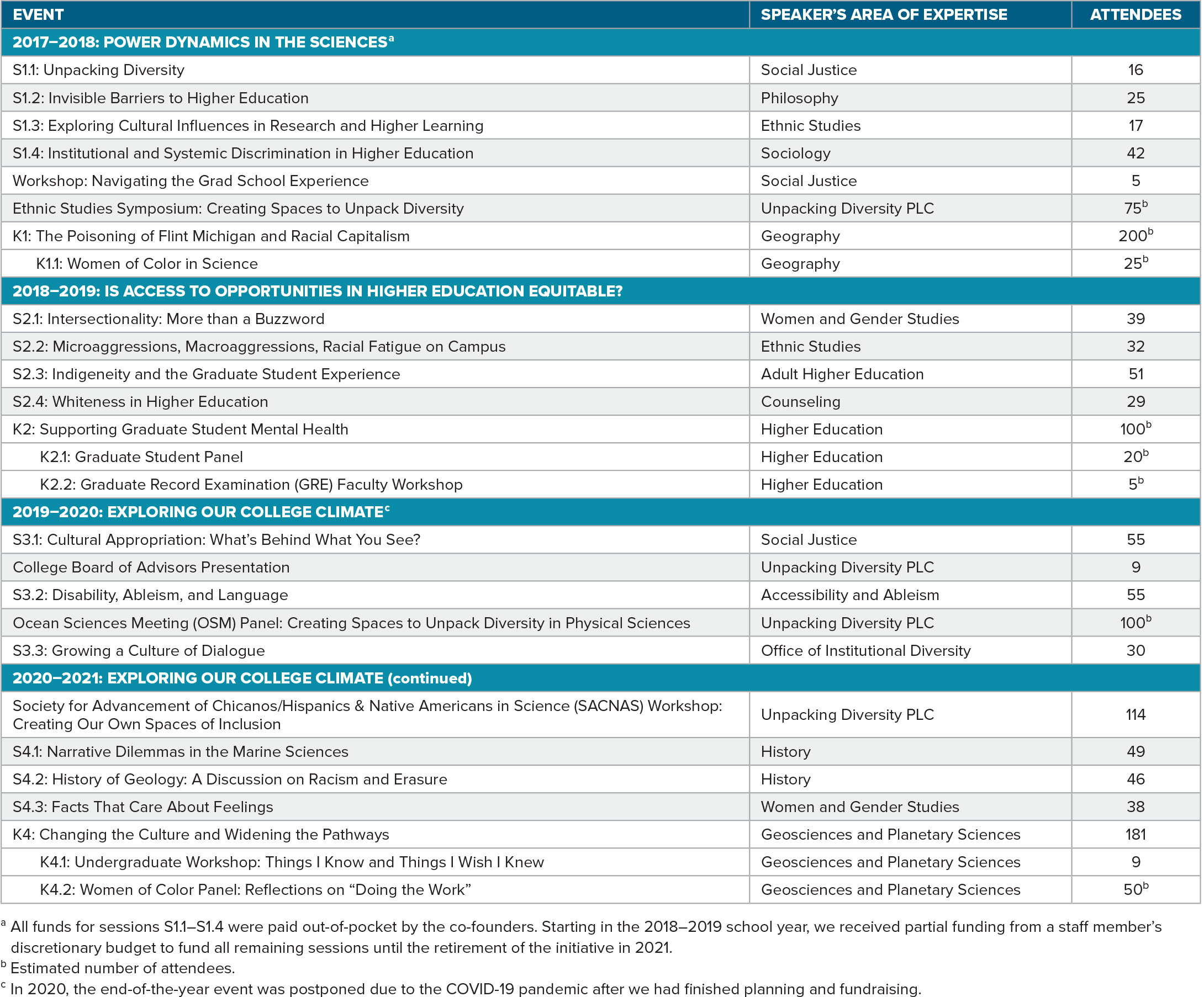

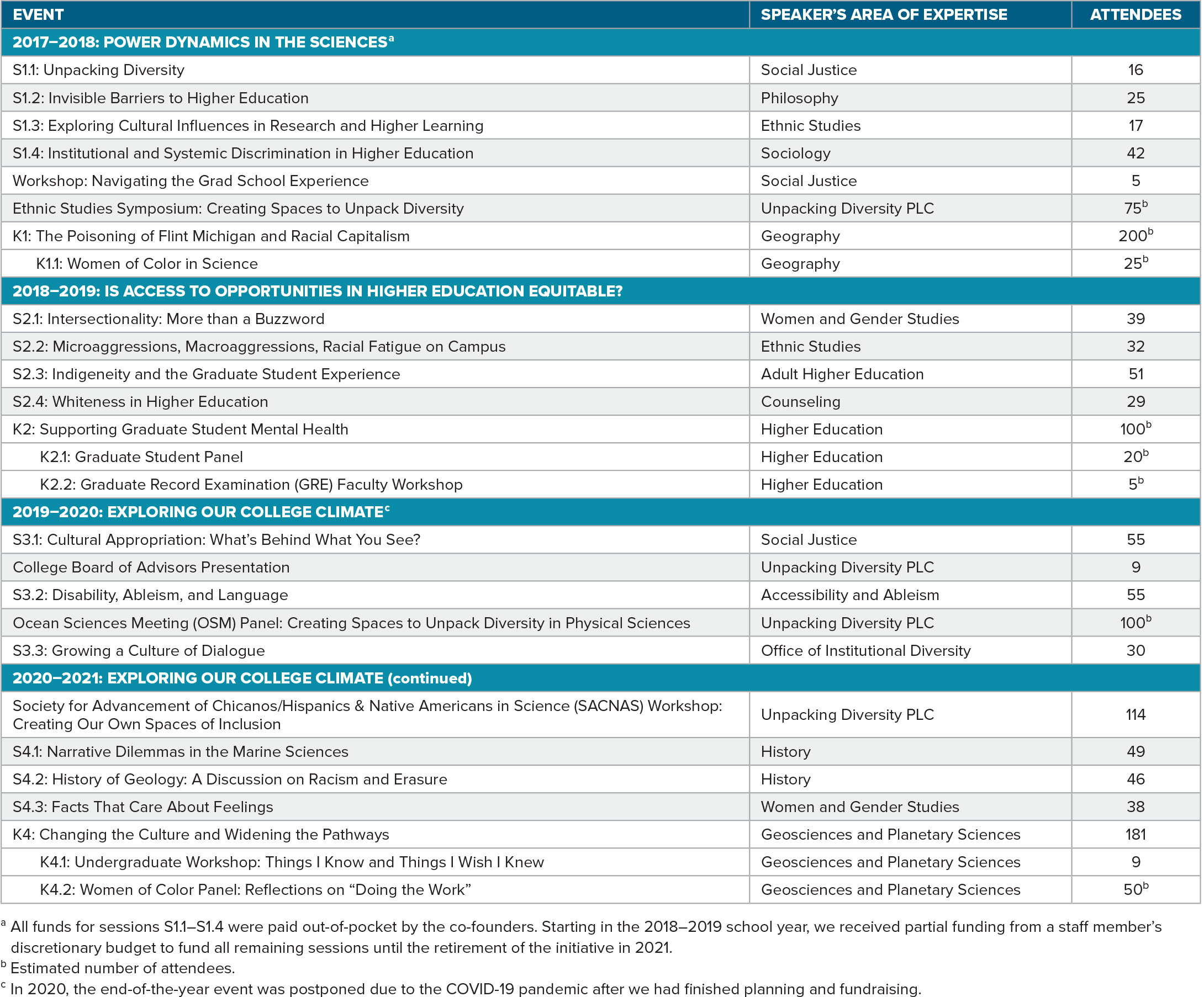

A professional learning community (PLC) is a type of educational model that describes a group of individuals with a common interest in improving education (DuFour, 2004). We applied the PLC framework to include a community of student organizers, session facilitators, and the audience, regardless of affiliation and position. A major component of Unpacking Diversity was a recurring, yearly seminar series that ran from 2017 to 2021 (Table 1). The seminar focused on equipping college members with the tools to recognize barriers in higher education and the factors that contribute to a harmful academic environment. In the following sections, we expand on the design of the seminar series and the evolution of Unpacking Diversity. We hope lessons from our experience can guide the creation and implementation of other critical DEIJ initiatives in the ocean sciences and provide grassroots organizers strategies for operating such a program effectively without becoming a detriment to their professional goals, scientific research, or personal well-being.

TABLE 1. The seminar series, end-of-year keynote events, and presentations organized by Unpacking Diversity from 2017 to 2021. Regular sessions catered to the geoscience college are labeled S1–S4. The end-of-the-year keynotes are labeled K1–K4. > High res table

|

This paper is written from the perspective of five Unpacking Diversity leaders who belong to underrepresented groups in the geosciences (e.g., women, Southeast Asians, Pacific Islanders, and Latinx). Our research disciplines encompass a wide range of expertise with little overlap (biological and physical oceanography, geography, water resources, and geology). We refer to the founders of Unpacking Diversity, who were active between 2016 and 2020, as the “co-founders,” and the next-generation leaders who were active from 2018 to 2021 as the “co-leaders.”

Understanding the Need for Unpacking Diversity

We, the co-founders, created Unpacking Diversity because we wanted to address and understand the underlying causes for students of color feeling like outsiders within our college, and consequently to make systemic cultural change in our scholarly community and the greater geoscience field. The persistent homogeneity of the dominant culture in the geosciences reinforces existing biases that systematically prevent the participation of underrepresented groups (Mattheis et al., 2019). Not acknowledging the realities of people from marginalized backgrounds can leave them feeling unseen, isolated, and inadequate. Their experiences are often dismissed and regarded as impostor syndrome and incompetence, which shifts the problem to the individual rather than acknowledging the institution’s role in othering individuals from nondominant identity groups (Nuñez et al., 2020). Guided and self-led learning on DEIJ research helped us, the co-founders, to navigate the social surroundings of our disciplines.

Creating the Community: A Blueprint

Structure of the PLC

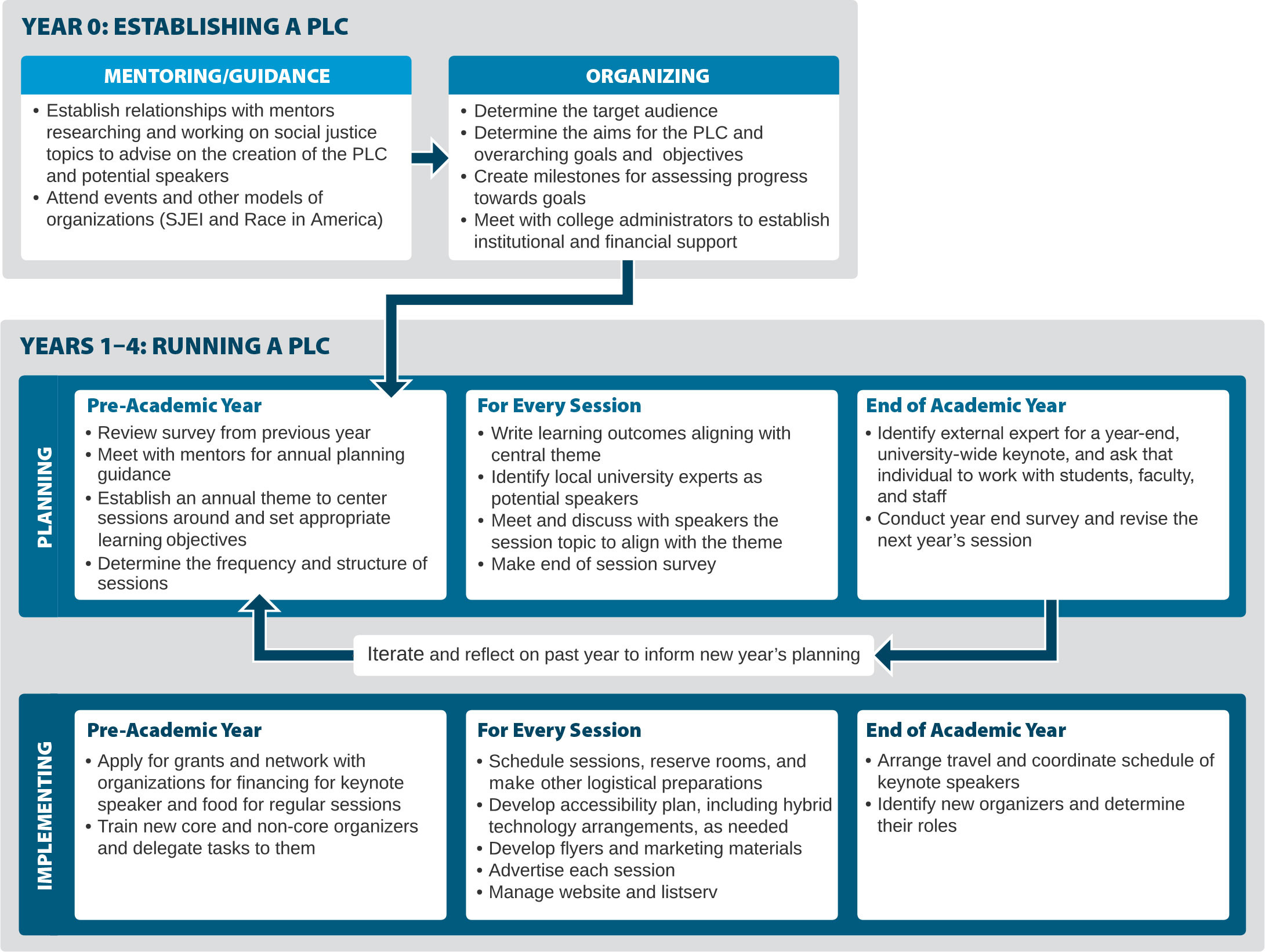

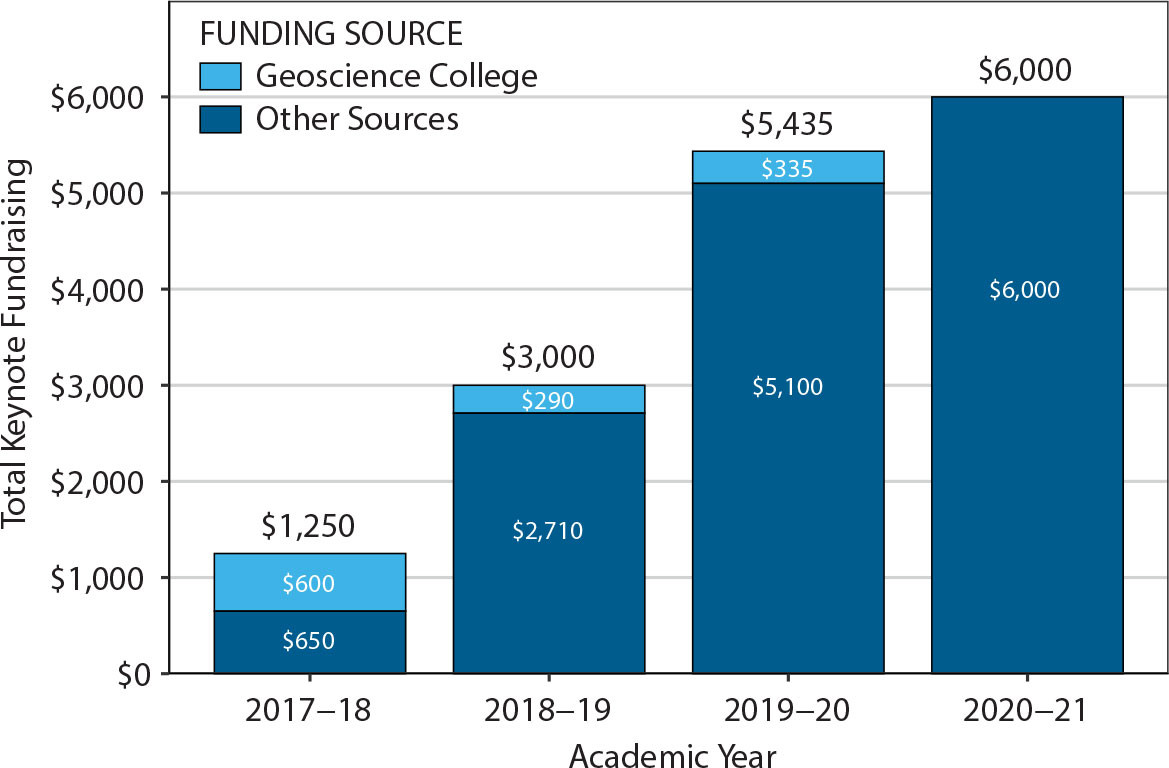

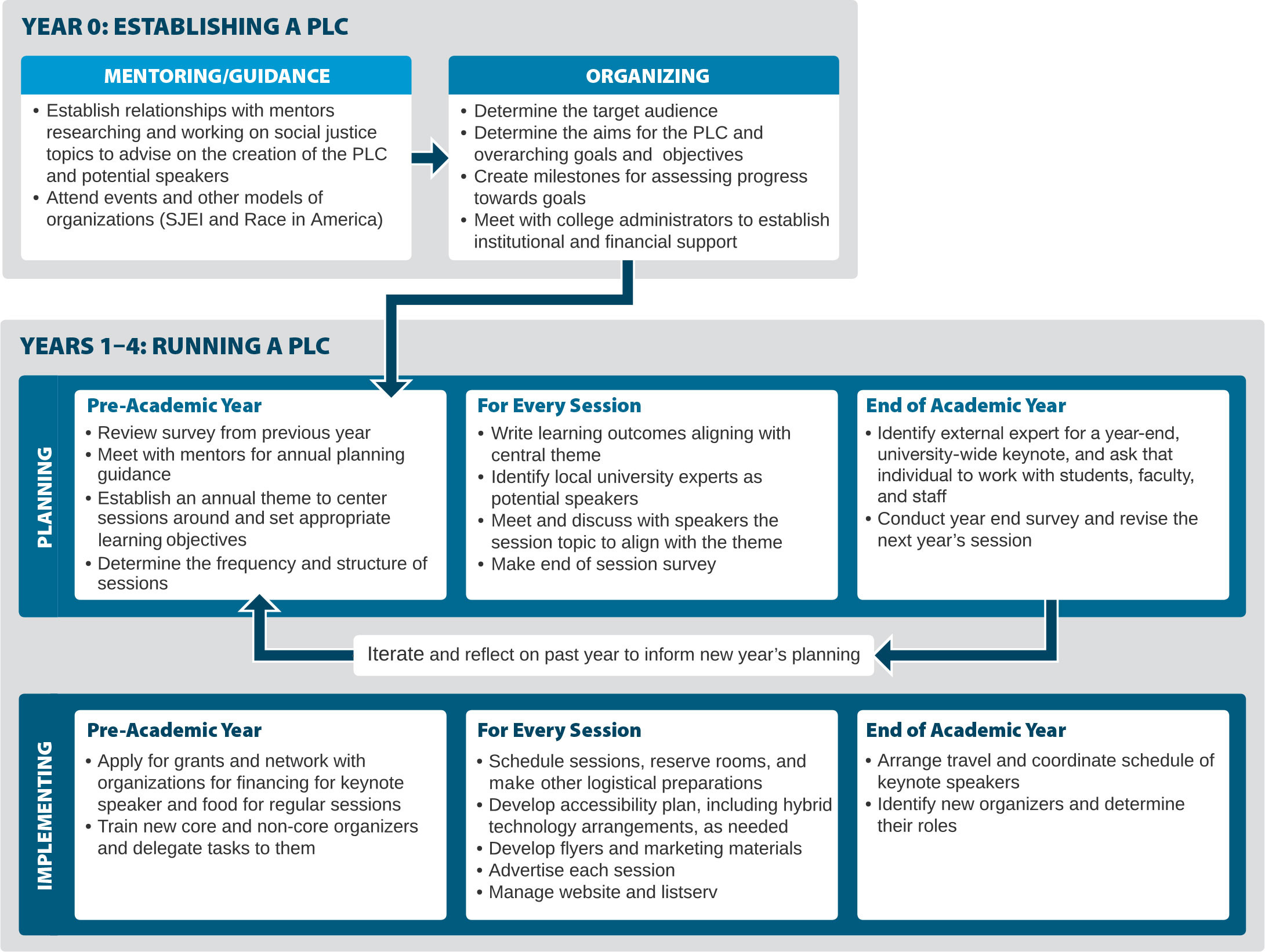

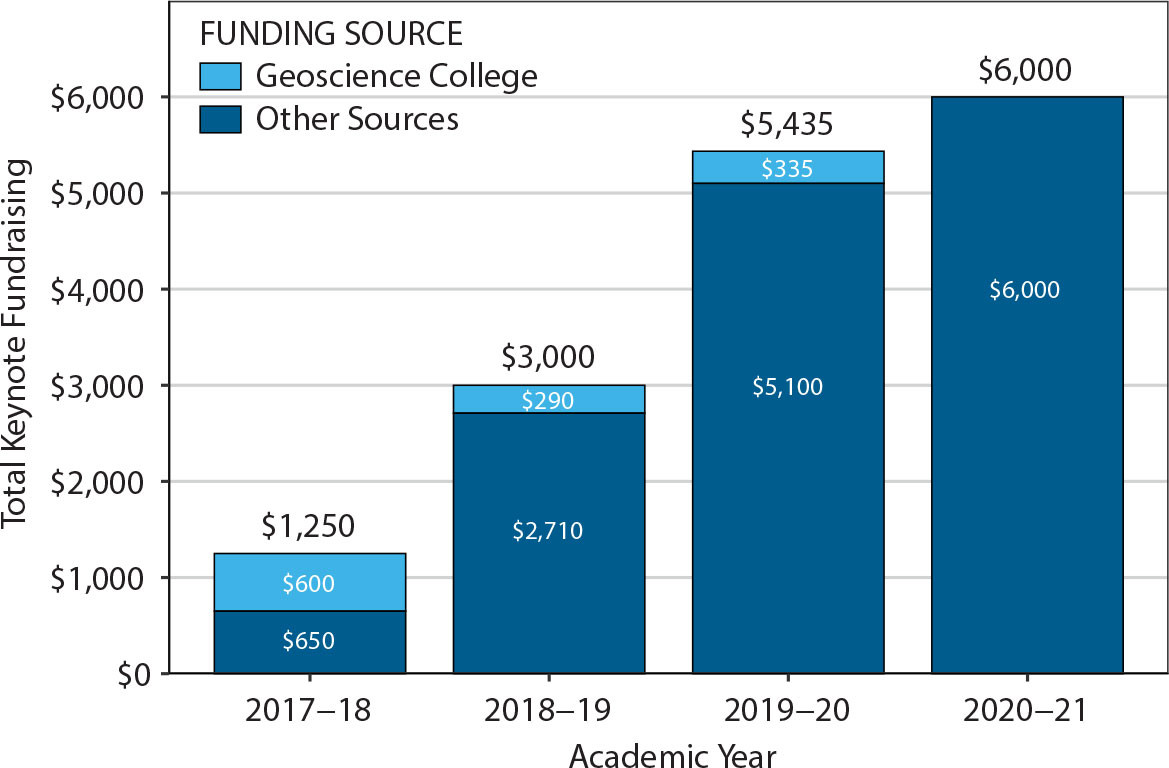

The seminar series was a major component of Unpacking Diversity. Table 1 provides an overview of the sessions and topics, and Figure 1 presents a “blueprint” that outlines the three tasks we completed annually: establishing, planning, and implementing a PLC. As we did not have expertise in establishing DEIJ programs, we relied heavily on mentors from the humanities and social sciences. The establishing stage was critical; it involved identifying our intended audience, elucidating Unpacking Diversity’s aims, and determining what we wanted to achieve. The next stage included planning and implementing Unpacking Diversity’s activities for the year (Figure 1). Our network outside the college continued to expand each year as we collaborated with student leaders from other colleges to bring guest speakers for year-end keynote events. As attendance at Unpacking Diversity events increased and our reputation grew, the necessity for more funds to support multi-day keynote events also increased (e.g., to pay for refreshments, travel, meals for speakers, advertising, honorariums); these funds were secured primarily from external sources (Figure 2). For the first year, seminar refreshments were paid out of pocket by the co-founders, as there was no funding in place for these events. In the following years, after sustained participation by community members, limited funding was secured from the budget of a staff member in the college.

FIGURE 1. Blueprint for establishing, planning, and implementing a seminar series as a part of a DEIJ Professional Learning Community. This diagram outlines the process used to establish Unpacking Diversity. Two key points central to Unpacking Diversity’s success to note are: (1) the pre-work of critically assessing the culture so its design fits the specific departmental environment, and (2) the iterative nature of the process over the four years of operation. > High res figure

|

FIGURE 2. Histogram showing total fundraising amounts (in US dollars, $) for yearly keynote programming by Unpacking Diversity PLC. Totals are shown for four consecutive academic years from 2017 to 2021 above each bar. Contributions from Unpacking Diversity’s home department comprise the category “Geoscience College” and are shown in light blue. Contributions from other colleges (departments), institutional offices, and non-institutional but affiliated organizations are summed up as “Other Sources” and shown in dark blue. Note that the funds raised in 2019–2020 were not used; the event was postponed due to pandemic disruptions. > High res figure

|

Discovering Success as a PLC

Part of organizing Unpacking Diversity was determining what success would look like and monitoring our efforts to ensure we were meeting our goals. At the start, we developed a proposal with the following core learning objectives to capture our aims (Treviño et al., 2017).

Objective 1: Build a strong background understanding of the history of discrimination and oppression in United States higher education.

Objective 2: Create a positive feedback cycle between students and faculty of openness and awareness of the experiences of students of color.

While our original goals focused on the experiences of BIPOC, through feedback from the community, we broadened our objectives to address topics with an intersectionality lens (Crenshaw, 1989) and to include seminars that addressed issues from other nondominant identities (e.g., LQBTQ+ in STEM, disabilities, and access in academia; see Table 1). To measure these objectives, we identified three criteria to demonstrate success: (1) attendance, (2) individual impact, and (3) external impact. Our attendance increased from an average of 25 to 46 people per session in four years (Table 1; S1–S4). In particular, high remote attendance was maintained during the COVID-19 pandemic, which indicated a continued increase in people’s interest. We conducted surveys at the end of the year to gauge participants’ main takeaways. Survey results showed attendees felt safe when discussing DEIJ topics, and the sessions helped attendees see experiences from different perspectives. Lastly, and somewhat unexpectedly, outside institutions and individuals were referencing and inquiring about Unpacking Diversity. Texas A&M Galveston cited Unpacking Diversity as an example of an effective initiative, and a similar organization at the University of Rhode Island, VOICES, took inspiration from the design and objectives of Unpacking Diversity (VOICES, 2019). Graduate students and faculty at multiple institutions approached us after we presented at the SACNAS (Society for the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science) National Conference, the Ocean Sciences Meeting, and over email about support and recommendations for creating similar initiatives. These interactions highlight the demand for open and safe spaces within the geosciences and demonstrate how Unpacking Diversity successfully created such a space.

Discovering Success as Graduate Student Organizers

Organizing for Unpacking Diversity was a transformative experience from which we derived personal and professional benefits. Although all organizers felt most benefits equally, the impacts of these benefits on our careers and lives varied depending on our backgrounds, research fields, and academic journeys. The following list summarizes some of the positive ways our involvement in Unpacking Diversity impacted us personally.

- We found that increasing our learning about the theory and research on these topics validated feelings of isolation and inadequacy experienced by the women of color organizers. It empowered us to call out systemic issues in real time and challenge policies perpetuating racism and exclusion in the sciences.

- For those of us with more dominant identities in the US higher education system, Unpacking Diversity provided opportunities for active learning and growth, concurrently instilling confidence in continuing work in DEIJ and becoming better allies.

- We expanded our professional networks and participated in multidisciplinary collaborations outside geoscience fields with communities that would not have been readily accessible through typical research endeavors.

- Throughout our seminars, we expanded our understanding of justice outside the areas of our personal experiences (e.g., disability/accessibility justice), which gave us space to practice creating equitable learning and research environments.

- Through this experience, we formed a community of long-lasting relationships and a resilient network of scientists. This support proved crucial during challenging times in our careers, reinforced the agency to remain in academia, and enhanced our self-worth as scientists.

Pillars of Success

While several factors contributed to the success of Unpacking Diversity, we reflected on which points were most impactful for creating an open and safe space. We identified four overarching categories that served as foundational pillars for our success.

Pillar 1: Support Inside and Outside the Geosciences

Having a supportive network was vital for the foundation and operation of Unpacking Diversity. As previously discussed, mentors outside the college guided us on the PLC structure and the topics for the discussion sessions and keynotes (Table 1). In addition, other forms of support and mentorship were instrumental in the success of Unpacking Diversity. First, institutional allies within the geoscience college supported us by encouraging attendance and advocating for us in challenging situations. Second, having job security with reasonable benefits advocated for by a graduate student union ensured we could organize alongside our other responsibilities. Third, for some of us, forming a peer community of women of color within a PWI provided support in navigating personal and professional challenges, as well as managing Unpacking Diversity. Finally, our White co-founder and co-leaders proved to be genuine allies as they used their voices to promote participation without centering whiteness.

Pillar 2: Thoughtful Designing and Planning

When we founded Unpacking Diversity, we were aware of a culture of resistance in the college to participate in DEIJ training. We considered the college’s culture and climate, providing a space for collective learning to navigate challenging conversations. To ensure the seminars were perceived as integral to the academic environment, we invited social science experts from within the university to speak in order to dissociate the topic from us—the organizers—and presented them as research talks rather than extracurricular events. Deliberate choices were made regarding the locations and timing of the seminars. Holding them in the same physical space and time as college research talks added legitimacy and value in the eyes of college members. The annual seminar series was also organized iteratively (Figure 1), incorporating lessons learned from previous years. Early planning enabled the creation of thematic topics and speakers, fostering a sense of continuity and encouraging repeat attendance. Recognizing the diverse schedules of community members, multiple modes of access were provided to ensure involvement, even for those with busy research cruises, fieldwork, and class schedules.

Pillar 3: Multifaceted and Persistent Advertising

Increasing attendance and continuity is challenging in a higher education setting, and our hands-on advertising approach contributed to Unpacking Diversity’s success. We used multiple advertising methods (e.g., flyers, email, word of mouth) and personally invited our advisors, lab mates, and others with whom we interacted closely. We explicitly highlighted the seminars’ importance in shaping our college’s culture and climate. By personally inviting people who were not typically engaged in DEIJ issues, we could communicate the welcoming and inclusive nature of the space—that truly everyone was invited. Our seminar attendance was initially low (Table 1); only our friends, academic advisors, and allies participated. However, as colleagues witnessed their peers’ active involvement, particularly by faculty members, they were encouraged others to participate as well.

Pillar 4: Graduate Student Leadership and Perspectives

As graduate students, we were new to the college community and brought perspectives that initially presented us as outsiders, but in the process of becoming more knowledgeable about the culture, we became insiders, which gave us the ability to make contributions and changes to the climate. We also benefited from the contributions of other master’s and doctoral students as well as postdoctoral scholars, who are often excluded from long-term institutional climate conversations. Over time, our activities fostered trust in Unpacking Diversity because the PLC was created and organized by graduate students who were deeply invested in improving the working environment that directly affected them.

Barriers to Long-Term Viability

After four years of success and increasing engagement on and off campus, we—the co-leaders—decided to retire and focus on our graduate programs during the pandemic. This decision was based on the three major barriers.

Barrier 1: Unpaid Labor and Service

Not all institutional service is valued equally. In particular, DEIJ service is often regarded as a “passion project” and not counted as official service (Armani et al., 2021). While there has been increased attention on DEIJ issues in academia, including the rise in demand for positions solely focused on DEIJ,1 this work continues to be disproportionately done by volunteers and grassroots organizers from historically marginalized backgrounds. For BIPOC academics, this minority tax—the burden of added responsibilities to achieve institutional DEIJ goals—often comes at the expense of advancing their research agendas (Gewin, 2020). In the context of Unpacking Diversity, the greater university community benefited from the time we invested in our DEIJ work, while our graduate student organizers often sacrificed their research hours. The burden of securing funding for the increasingly popular seminar and keynote speakers (Figure 2) was particularly time-consuming, yet vital to the growth and success of the PLC.

Barrier 2: Hypervisibility and Conflicting Priorities

The co-founders created Unpacking Diversity in their final years of graduate school. The co-leaders benefited from the institutional knowledge and peer mentorship from this generational overlap. However, two years into the establishment of the PLC, all the co-founders had graduated. This decrease in organizers coincided with increased attention on Unpacking Diversity due to its previous year’s success and the current attention to DEIJ around the nation. While we, the co-leaders, successfully maintained Unpacking Diversity during the COVID-19 pandemic, we concurrently experienced delays in our research milestones. When in-person classes resumed in fall 2021, the number of interactions we had with faculty and administrators was much higher than what the average graduate student experiences. Our perspectives began to be solicited beyond the confines of Unpacking Diversity, which we had created to hold intentional DEIJ dialogue. Due to the power dynamics between students and faculty, accepting requests did not always feel optional. The growing demand for DEIJ service imposed on us further disrupted our focus on research and intensified feelings of being tokenized.

Barrier 3: Shrinking Peer Support Network

In the beginning, Unpacking Diversity was a closely embedded and cohesive network of graduate student friends, which was beneficial for gaining key resources, establishing trust, and gaining a positive reputation among graduate students of marginalized backgrounds. However, transferring network ties can be difficult (Kim et al., 2006). During the pandemic and periods of remote work, we, the co-leaders, focused on maintaining regular communication over email with administrative staff and co-sponsors between the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 academic years to secure a budget for an accessible virtual keynote event in spring 2021. Such relationships with staff and sponsors could not be transferred fast enough to graduate students unfamiliar with the university’s event planning and finance tools. As the pandemic progressed, co-leaders had fewer opportunities to transfer knowledge—as well as the organizing load—to new graduate students. Hence, strong early network ties and friendships did not guarantee long-term continuity of Unpacking Diversity with new cohorts of graduate students, particularly given the extenuating pandemic circumstances.

Although the college and community continued to benefit from Unpacking Diversity, there came a moment when the barriers outweighed the personal benefits the co-leaders acquired from their involvement in the PLC. The organizers had increasing leadership responsibilities in the college outside the original scope of Unpacking Diversity without commensurate compensation or structural support to advance their research and academic milestones. Ultimately, we retired Unpacking Diversity to ensure the co-leaders could have the time and space to pursue their scientific career goals. However, the network of peers and the collaborative relationships we formed during organizing still exist and continue to support us in our careers.

Recommendations for Other Graduate Student Grassroots Initiatives

Following our experience with the creation, organization, and discontinuation of Unpacking Diversity, we identify recommendations for grassroots organizers and institutions to enable successful and long-lasting DEIJ initiatives within academic institutions, particularly focusing on those established, organized, or involved with graduate students.

1. Establish Boundaries and Safeguard Organizers

- Graduate student grassroots organizers should set clear boundaries from the onset regarding when, where, and how they will hold DEIJ conversations with the broader community. Due to the power dynamics present, faculty and leadership must play a vital role in safeguarding and respecting these boundaries.

- The academic and emotional labor graduate student grassroots organizers provide is transformative and often driven out of necessity to survive in academic spaces. Organizers grow personally and professionally while creating a community benefiting their departments and universities. The balance between these personal growth and institutional benefits should not tilt towards the latter.

2. Foster Multidisciplinary Collaboration and Peer Mentorship

- Graduate student grassroots organizers should partner with experts in DEIJ topics to unpack the social justice issues directly impacting their academic community and create a PLC tailored to their college or department. Embracing collaboration beyond the geosciences broadens the conversation on scientific practices and promotes an inclusive approach to research.

- Organizers should invest time nurturing the relationships built from organizing together, both among peers and with mentors. These connections increase our resilience as individuals and can be long-term sources of mentorship and institutional knowledge.

3. Solicit Institutional Support for Graduate Student DEIJ Grassroots Programs

- Institutions must contribute administrative and financial support, preserve institutional memory, foster community buy-in for DEIJ goals in order to maintain an effective and socially engaged learning community, and reduce reliance on unpaid graduate student labor. Students involved in DEIJ efforts should be compensated, and the burden of funding these initiatives should not fall on them.

- Institutions can support the self-efficacy of graduate students by reducing barriers (e.g., restrictive email/cybersecurity policies) to communicate within departments and by designating clear points of contact for communicating across departments and hierarchies.

To promote growth and inclusivity, institutions must recognize the transformative potential of grassroots DEIJ initiatives, address institutional barriers, and amplify student voices. By doing so, universities can create an environment that values personal development while reaping the institutional benefits of diverse and empowered student-led initiatives.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the time and contributions of all the people who supported Unpacking Diversity. For a full list of acknowledgments, see https://unpackingdiversity.wixsite.com/ceoas/tos2023. Thank you to Benjamin Keisling for providing helpful and refreshing comments. JW-A is funded by the National Science Foundation GRFP (NSF#1840998). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.