Introduction

The Arctic is a critical region that is undergoing rapid environmental changes related to warming air and water temperatures, sea ice losses, and changing habitats. Surface air temperatures are currently warming at four times the rate of the global average (Rantanen et al., 2022). Summertime Arctic sea ice extent is declining (e.g., Barnhart et al., 2016; Stroeve and Notz, 2018), and many models predict that the Arctic will be ice-free by 2050 (Notz and SIMIP Community, 2020), or possibly as early as 2030 (Heuzé and Jahn, 2024), meaning that Arctic sea ice extents would be <1 million km2 for at least one day per year. These changes will have ramifications for all parts of the environmental systems that comprise this unique and complex region. Commensurate with these changes and their implications for global ocean circulation, global climate, ecosystem health, and regional food security, there is an increasing demand for scientific research in the Arctic to improve environmental understanding and the prediction ability of models. Furthermore, the Arctic is a realm of increasing geopolitical pressure, where soft diplomacy through international scientific cooperation can help to mitigate tensions (The White House, 2022).

Polar research vessels are a critical link in Arctic science capacity. However, using them to accomplish timely, high-quality research requires scientists to serve in leadership positions in order to effectively plan and organize surveys, manage mobilization of equipment and personnel, communicate well with captains and crew, and build positive community relations. Chief scientists can also find themselves needing to navigate and mediate interpersonal dynamics among team members as well as complex dynamics among the science community, agencies, communities, and international parties.

In the US Academic Research Fleet, which is coordinated by the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS), chief scientist training cruises have been an effective means of preparing new generations of researchers to lead successful science campaigns over the last decade (Reimers, 2011; Reimers and Alberts, 2012). Additionally, the Crustal Ocean Biosphere Research Accelerator (COBRA) has trained several cohorts of fellows through a 16-week Master Class focused on designing and implementing deep-sea oceanographic expeditions (Rotjan et al., 2023). However, working in the Arctic poses unique operational and planning challenges. Many Arctic ports are remote and difficult to access (and/or inaccessible during winter months), have limited infrastructure, and thus require unique field safety considerations. Science party mobilization and demobilization must frequently adjust to limiting weather conditions that call for extensive contingency planning. Icebreakers and ice-capable vessels can only safely operate within specified ice thickness conditions, so care must be taken to iteratively adjust science operations while monitoring rapidly changing conditions and avoiding hazardous situations. Trips that include ice stations warrant a different type of planning than is needed for typical oceanographic stations—for example, assessing ice thickness, managing division of personnel and equipment between the vessel and the ice, and maintaining bear watches. Most US polar research vessels currently in service are also operated according to different management structures than the US Academic Research Fleet—for example, the US Coast Guard Cutter (USCGC) Healy is a vessel with multiple mission demands that include but are not limited to scientific research. Other ice-capable vessels previously used by the US Antarctic Program, such as R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer, have been operated through a third-party contractor. Future federal icebreakers (e.g., USCG Polar Security Cutters or Arctic Security Cutters) may also have opportunities to support polar science while conducting other statutory missions, and scientists will need to know how to effectively engage with these platforms.

In order to help prepare an incoming generation of researchers to effectively use polar research vessels (and icebreakers in particular), navigate these unique management structures, and thereby advance polar science, we proposed and were funded to assemble a training program modeled after previous Early Career Chief Scientist Training Cruises (Reimers, 2011; Reimers and Alberts, 2012) but with a focus on leadership of cruises in polar regions. In 2023 and 2024, we focused our efforts on training junior scientists to plan and conduct cruises on R/V Sikuliaq operated by the University of Alaska Fairbanks College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences and on USCGC Healy. The 2023 program was designed primarily for Arctic research cruise training. In 2024, we expanded the applicant pool to allow participation from Antarctic researchers, which enabled the cross-pollination of the research community between the poles. While the US National Science Foundation (NSF) has supported field training for early career researchers at the US Antarctic Research Program’s McMurdo and Palmer Stations, with opportunities for short excursions from Palmer Station aboard R/V Lawrence M. Gould in 2016, these efforts were focused on a training cohort that was new to Antarctic field science. Our distinct goal was to enable those with preexisting field research experience to step into key leadership roles in seagoing polar science and to eliminate knowledge barriers that might prevent otherwise capable scientists from embracing these roles.

Here, we present details about the motivation and needs for training, the design and implementation of the 2023–2024 program offered through our grant from NSF, outcomes as viewed from participant surveys, and perspectives on future training ideas, needs, and opportunities.

Motivation and Needs for Training

From an individual perspective, the process of requesting, planning, and successfully leading an icebreaker cruise can be daunting for many junior scientists. Part of the problem lies in differing preparatory experiences in graduate school. Some students are trained at universities that have large seagoing research programs and mid-career to senior personnel who have capacity for including junior scientists (i.e., students, postdoctoral scholars, and junior principal investigators) on cruises. For example, several large Arctic monitoring programs have been supported for years by oceanographic centers such as the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the University of Washington, and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Such programs have provided pathways, facilitated by senior chief scientists, for junior researchers to become routinely engaged in seagoing work and sometimes in planning for such work. However, students trained at smaller schools, schools that do not have R1 classification (i.e., with “very high research activity” under the Carnegie classification system), and/or schools without large seagoing research programs may have less access to this type of training. Indeed, a significant proportion (30%) of UNOLS member institutions are not R1, which underscores the need to provide mentorship and training opportunities for those at smaller institutions to fully utilize the academic research fleet and polar icebreaking vessels. Furthermore, within the last several years, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated problems of access for students at all types of universities. Many cruises were canceled or operated with very minimal staffing. New proposals for Antarctic ship time were discouraged in a 2023 NSF letter to the community (NSF Dear Colleague Letter 23-117) due to the post-pandemic backlog of projects. A similar bottleneck may occur with the non-renewal of the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer contract with NSF at the end of 2025.

Even when junior scientists have had opportunities to go to sea and do research with mentors, as they advance toward professional research and tenure-track faculty roles, they are often expected to step into leadership and facilitation roles for increasingly complex science teams with few formal support structures or leadership training. Undergraduate and graduate education rarely prioritizes development of the “soft skills” that are critical to managing research teams in the field or more generally any team-based workforce (Brungardt, 2011; Karimi and Pina, 2021), including dealing with interpersonal dynamics; communicating effectively with technicians, vessel operators, crew, and diverse science teams; making informed decisions; organizing team activities; and adapting priorities as conditions inevitably change to ensure successful scientific outcomes for the majority. Indeed, the gap between the training graduate students typically receive while pursuing their degrees and the competencies they must possess to be successful in academic and/or alt-academic career paths has been the impetus for a number of NSF-funded training programs, including the COBRA Master Class (Rotjan et al., 2023) and the UNOLS chief scientist programs (Reimers and Alberts, 2012), as well as additional trainings focused on stakeholder engagement and communication (Hunnell et al., 2020).

It can be challenging for junior scientists to serve in these facilitation roles because it takes them away from what they know and have been trained to do (i.e., be experts in managing their scientific research component) and into the unchartered territory of managing an entire portfolio of science objectives, facilitating science with which they may have little familiarity, and working with a diverse set of people. Furthermore, there are likely inadvertent barriers that prevent junior scientists from feeling comfortable leading field campaigns—this can include small personal networks that exclude those knowledgeable in vessel operations and science support at sea, lack of familiarity with key procedures and support structures, and a perception that leadership roles are only for very established scientists. Many “unwritten rules” (see Rotjan et al., 2023) exist in seagoing science. Knowledge needed to successfully lead a cruise is often accumulated through experience and informal sharing. Given this factor and the logistical challenges of polar field science, the increased sensitivity surrounding environmental compliance, and the need to mitigate the impacts of research on subsistence hunting activities, junior scientists are likely to be hesitant to embrace these leadership roles. In the US Arctic sector, this hesitancy has been manifested in a relatively small pool of investigators who have served as chief scientists over the past two decades.

The pace of environmental and geopolitical change in polar regions and the important role these regions play in global ocean connectivity make development of the next generation of scientific leadership critical in order to maintain robust and vigorous scientific inquiry in the region. Avoiding stagnation in leadership serves multiple goals. First, it serves US national interests to develop a vital scientific workforce that can bring state of the art science and cutting-edge tools to bear on fundamental, continually evolving research questions. Second, it advances the human pursuit of science by introducing fresh perspectives that may challenge existing paradigms and lead to transformational understanding (Hill et al., 2016; Berhe et al., 2022).

The Training Program: Design and Implementation

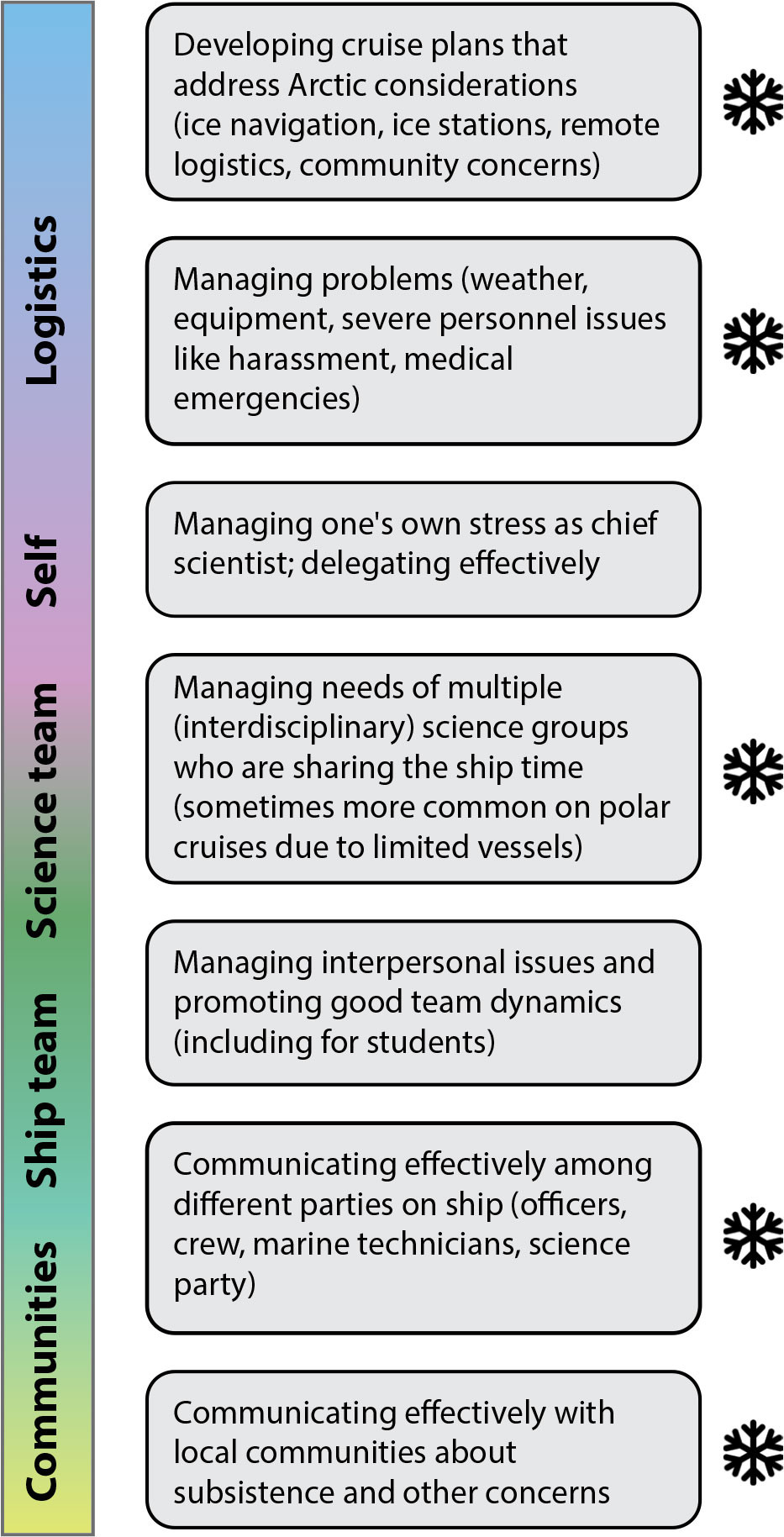

Polar Chief Scientist Training Modules

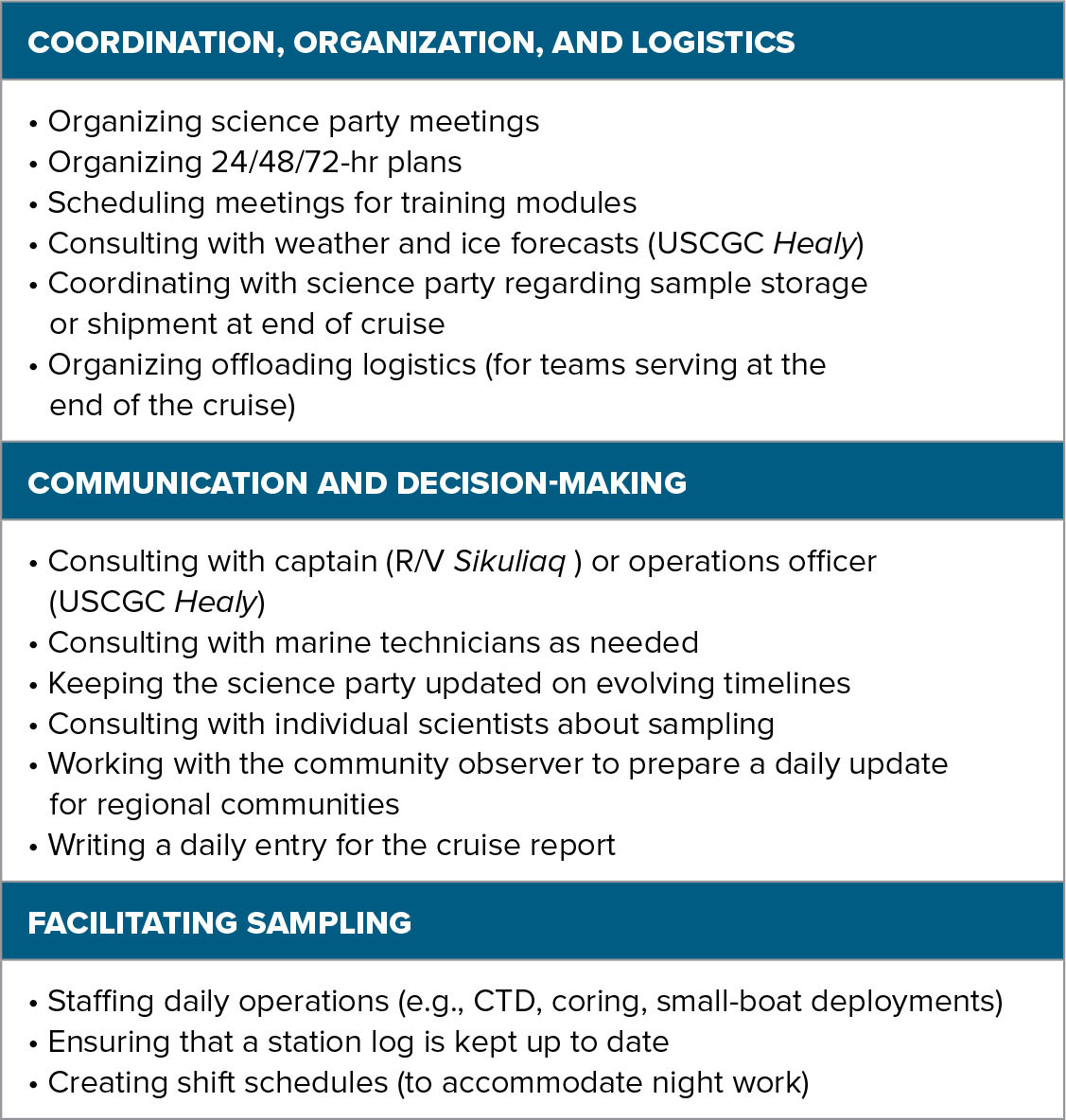

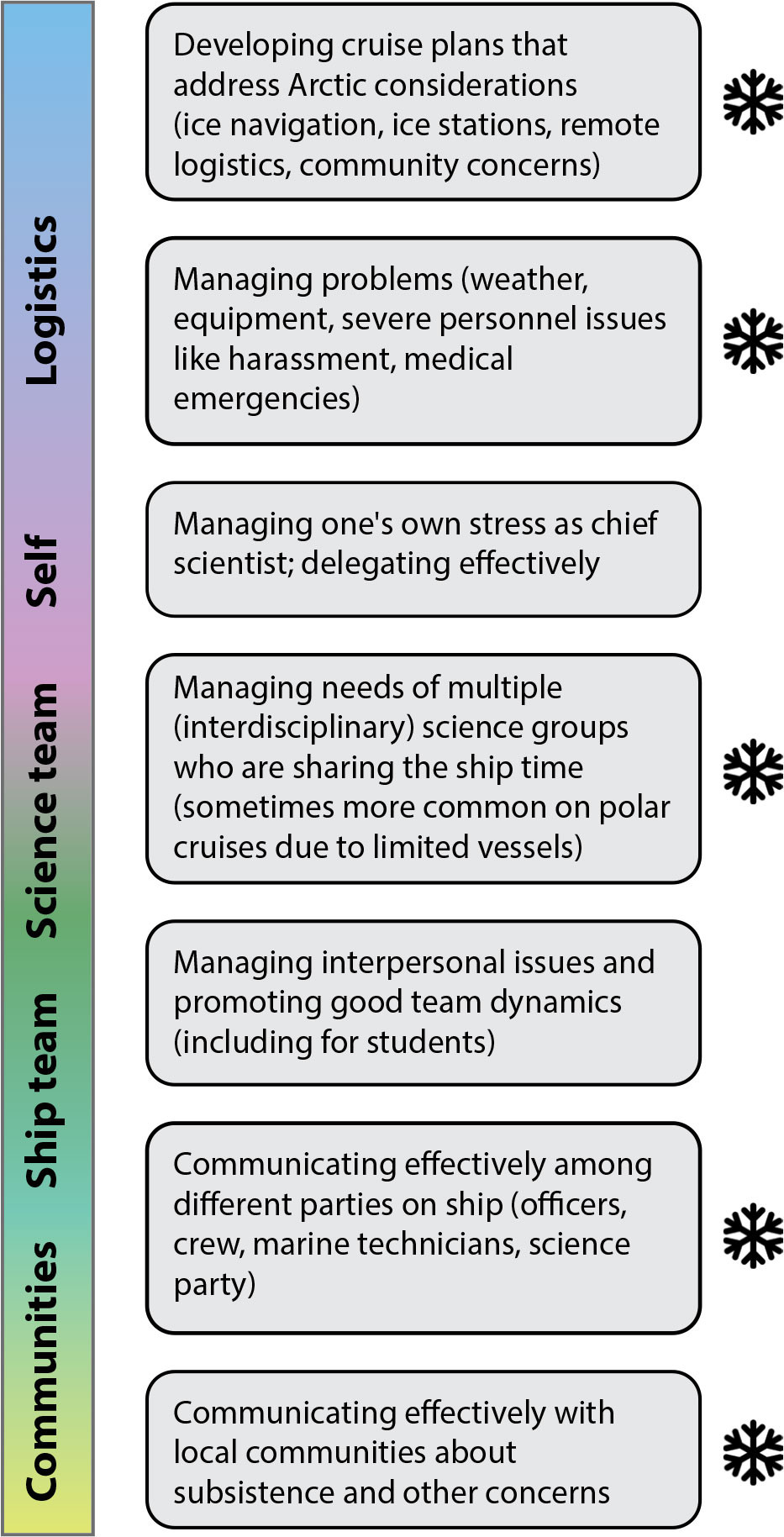

Although our training program was inspired by past UNOLS chief scientist training efforts, we developed unique modules to address barriers specific to junior scientists interested in leading polar research cruises. These included (1) face time with key facilitators of seagoing polar science from NSF, UNOLS, R/V Sikuliaq, and the US Coast Guard in order to broaden their professional network and help them better understand management structures and contacts for planning cruises on icebreakers and/or in ice zones; (2) opportunities to engage with local Arctic community members and learn best practices for consultation in cruise planning and communication while underway; (3) practice in developing cruise plans that address unique considerations of Arctic cruise planning, including polar field safety, remote and cold-region logistics contingency planning, and permitting in Arctic locations; and (4) immersive experience in planning and leading complex, multidisciplinary cruises that serve a broad array of user needs. To further augment this list, we surveyed participants during pre-cruise meetings regarding their biggest concerns with respect to becoming a chief scientist. The four module topics were reflected in participant responses, in addition to broader (i.e., not polar-specific) concerns regarding interpersonal dynamics, conflict management, and leadership of teams (Figure 1). Accordingly, we made space for focused discussions on these topics in our 2023 and 2024 programs.

FIGURE 1. Spectrum of concerns about serving as chief scientist noted by participants during the pre-cruise planning phase of the training described here. Responses from both the 2023 and the 2024 cohorts were combined and grouped into seven general concerns. The snowflake icon denotes concerns that have some unique aspects for polar cruises (see text). > High res figure

|

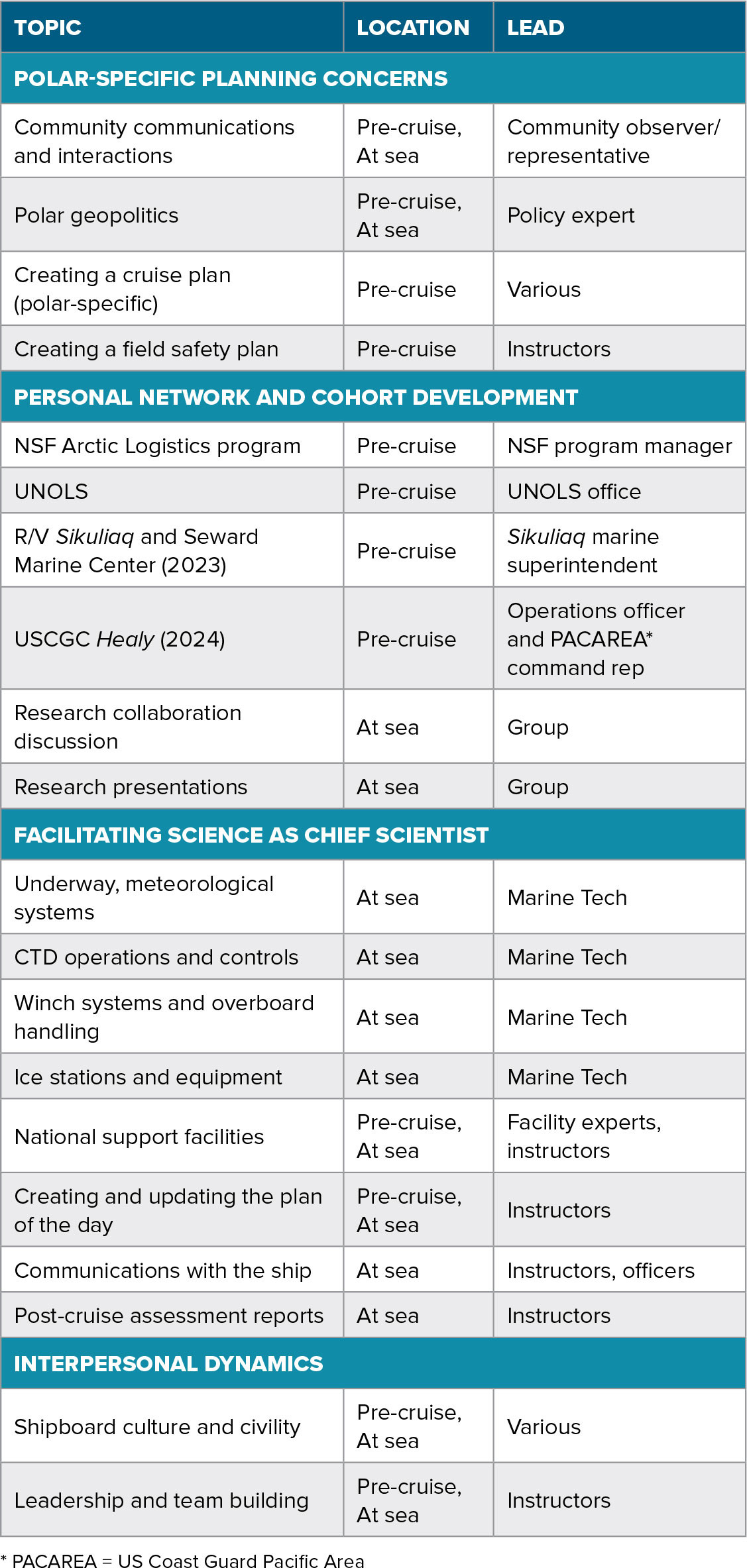

These training elements were interwoven into multiple instructional modes throughout the program, including a series of pre-cruise planning meetings, a pre-cruise symposium, and immersive experiences at sea. Emphasis on active participation and “learning by doing” was central to the training effort. Table 1 summarizes the various components of the training that were offered in different modes, and further details on many of these modules are discussed in following sections.

Pre-Cruise Virtual Planning

The first step in the training program in both years was a series of virtual pre-cruise planning meetings conducted via Zoom video conferencing. Ideally, this process would occur in the six to nine months leading up to a cruise to give participants an opportunity to be involved in as many stages of the pre-cruise planning activities as possible. In 2023, for a training program on R/V Sikuliaq, we were only able to begin holding these meetings for a June cruise in March, when we engaged participants in discussions about requesting ship time and environmental clearances and talked about planning infrastructure needs. We covered the UNOLS Ship-time and Marine Equipment Request Form (SME), which is housed within the Marine Facilities Planning (MFP) portal. Participants also joined a formal pre-cruise planning meeting with the science operations manager for R/V Sikuliaq and worked in teams to develop a cruise plan, which was effectively organized by sampling mode (i.e., water-column and seabed sampling teams).

In 2024, we held five pre-cruise planning meetings between March and July in preparation for an August training cruise aboard USCGC Healy. These planning meetings were designed to help participants develop an interdisciplinary cruise plan that allocated the available ship time to meet the majority of participant sampling goals, including water column, seabed, and sea ice sampling as well as small boat work. Participants also worked in small teams to produce field safety plans and then merged them into a combined document for the cruise. While these field safety plans may be dismissed as pro forma to those embarking ships in major cities, they are of the utmost importance in remote polar regions with reduced infrastructure and unique cultural sensitivities. The mental exercise of gathering resources and developing plans to mitigate the potential challenges of polar field science was an important part of the leadership training. Participants also completed standard operating procedure documentation for equipment they would install and/or deploy from USCGC Healy. Planning meetings were held with marine technicians (Ship-based Science Technical Support in the Arctic, STARC), as well as USCGC Healy’s marine science officer and operations officer.

In-Person Pre-Cruise Workshop

In both years we held an in-person pre-cruise workshop immediately before the cruise. This activity allowed participants to (1) meet and learn from some mentors who were not able to sail, including UNOLS and NSF program managers, thus contributing to our program goals of allowing participants to develop relationships with key seagoing facilitators; (2) build the strength of their cohort (in terms of interpersonal dynamics) before going to sea. In other words, our goals were to provide additional content and networking opportunities within the framework of the training program and to model how chief scientists can establish good working relationships with the cruise teams before leaving the dock.

In 2023, we held the workshop for one day at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Seward Marine Center, R/V Sikuliaq’s home port. We received feedback that the program was too condensed (i.e., too much of a good thing in one day). In 2024 we held the workshop for two days in Edmonton, Canada. While this was less ideal than holding it at our port of departure, planned to be Kugluktuk, Nunavut, Canada, holding the workshop there would have placed undue burden on this remote community’s lodging resources, which were serving governmental activities during the summer. (As it happened, mechanical issues with ship resulted in actual departure from Nome, Alaska.)

Training Cruise

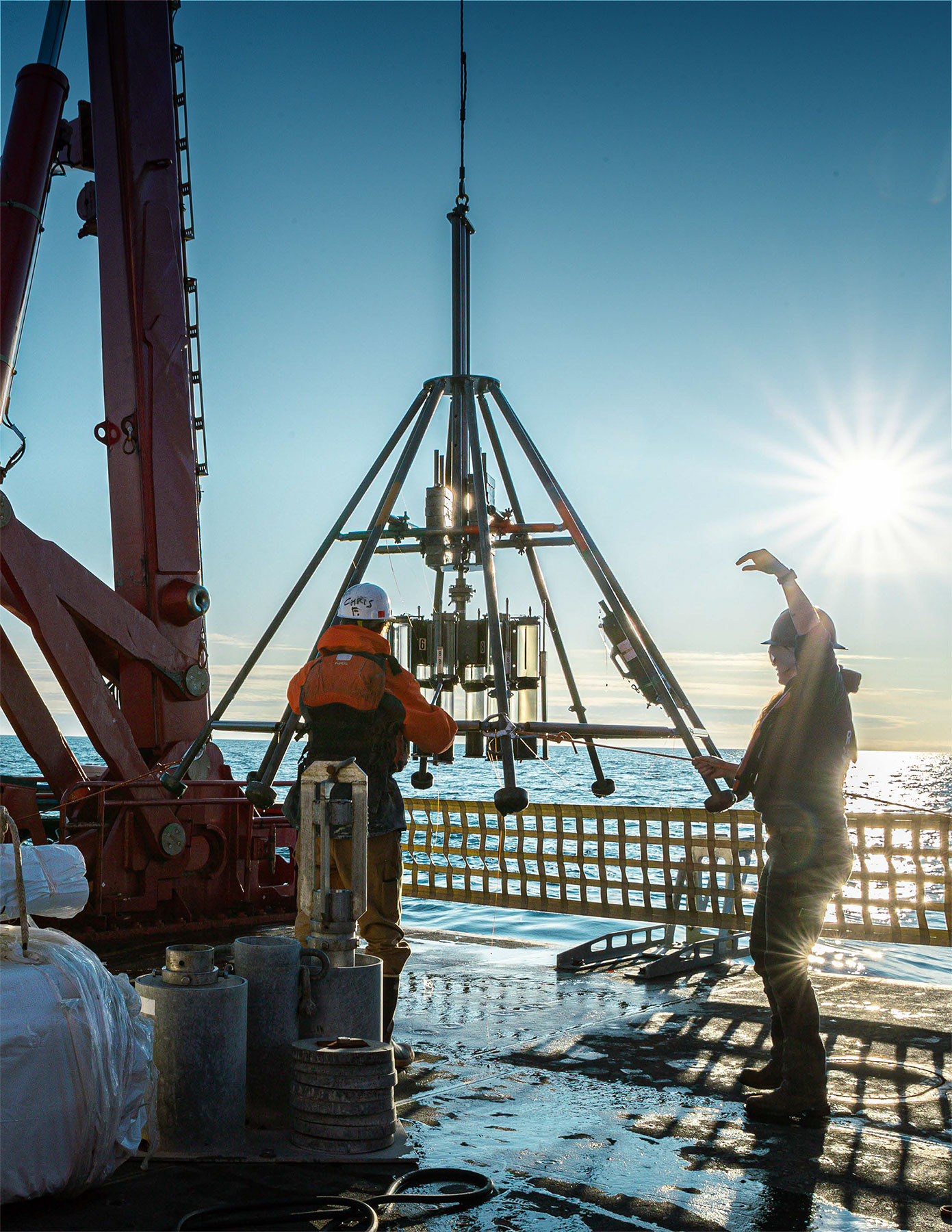

The at-sea program included mixed training modalities: (1) serving as co-chief scientist, (2) conducting scientific operations, (3) learning about at-sea operations from vessel personnel, and (4) developing a cohort through shared experience (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Examples of participant engagement from both cruises. (a) A physical oceanographer and a remote sensing specialist assist a benthic ecologist with sample processing. (b) Participants work to develop their science plan for the next few days. (c) A marine technician and a participant recover a multicore. (d) A participant studying clams shares knowledge with paleoceanographers. (e) Participants confer to coordinate small-boat deployments. (f) Two participants (center) join the daily captain’s briefing on USCGC Healy. Photo credits: (a,f) Matthew Masaschi, USCG, (b–d) Lloyd Pikok Jr., UIC Science/Battelle, (e) Emily Eidam. > High res figure

|

The first mode consisted of an opportunity for every participant to serve as an acting co-chief scientist together with one of their peers for a 24–48-hour period. We initially assigned people to serve in pairs because of the short duration of the cruise in 2023, but we found that the peer-to-peer mentoring created by these pairings was incredibly effective, so we repeated it in our 2024 program. Because of the longer cruise duration in 2024, we were able to rotate participants for 48-hour chief scientist assignments. During the first 24 hours, a participant would act in a supporting role alongside another participant who had served the day before, and then continue for a second day with a new supporting co-chief. Creating this staggered peer mentoring system (with one person in the pair having 24 hours more experience than the other) was even more effective than the team strategy employed in 2023.

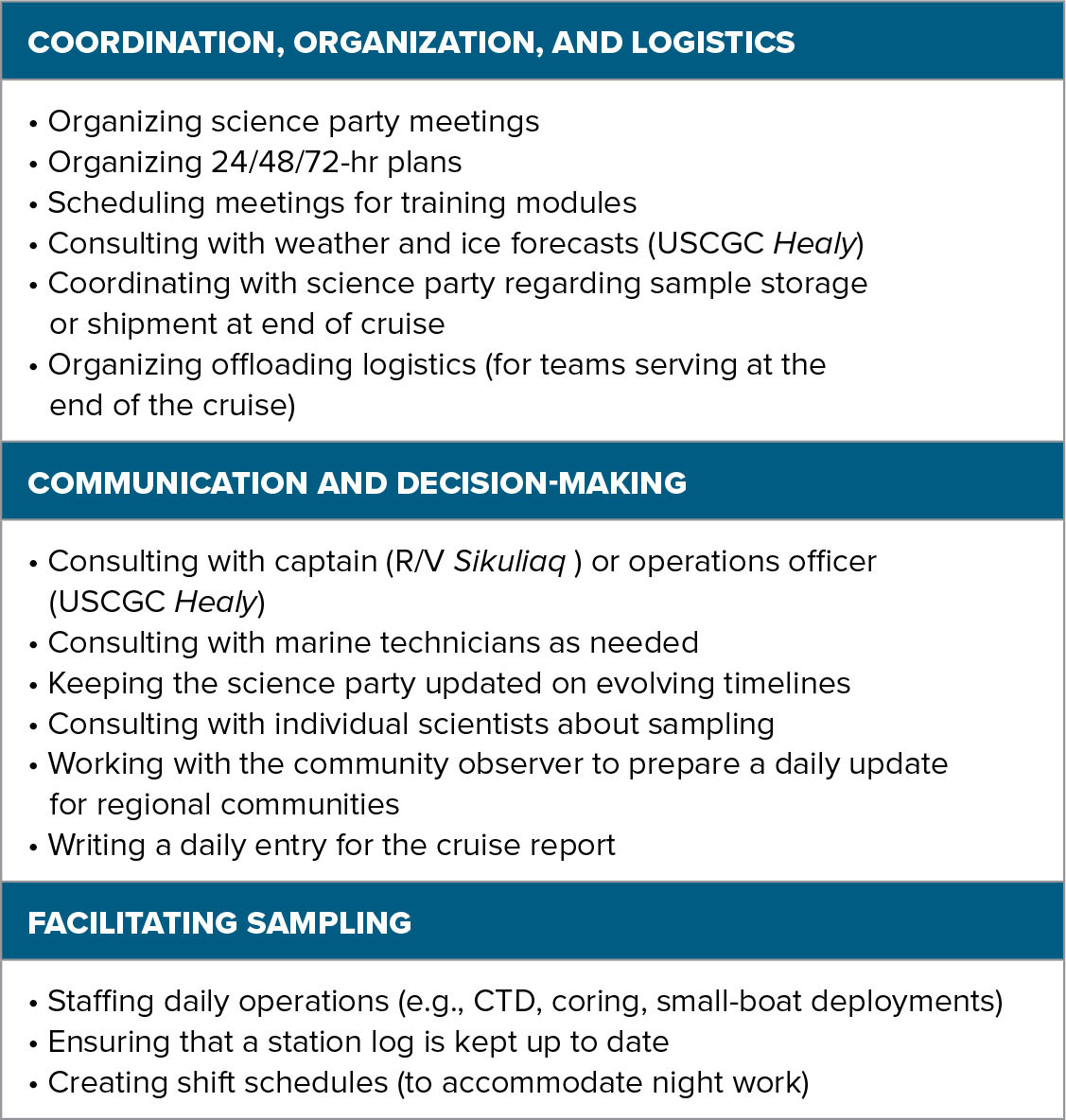

Participants used each other as sounding boards, divided tasks, and consulted each other regularly while acting as co-chiefs. Daily responsibilities of the co-chiefs (Table 2) included communicating effectively with the science team, the marine technicians, and the vessel captain or operations officer (depending on vessel) to plan and execute science operations (Figure 2a); plan for science team staffing and equipment readiness; and prepare daily updates together with the onboard community observer to keep local nearshore communities informed of vessel movements. Co-chiefs were responsible for making operational decisions in consultation with vessel personnel, maintaining a forward outlook on activities (e.g., plans for the next 24, 48, and 72 hours), and managing communication of changes in timing of any operations (Figure 2b,e). In fact, one of the most challenging aspects of this part of the training was the need to adapt to changing conditions—an experience that provided valuable insights into the demands of being a chief scientist. Participants had to adjust their plans in response to equipment malfunctions, storms, operations that were slower than expected, and changing science party needs. They also had to maintain regular and timely communication with their science team to inform people of these changes and help individuals adapt as needed (e.g., if a particular station had to be canceled due to weather-related slowdowns).

TABLE 2. Daily responsibilities of the acting co-chief scientists. > High res table

|

The second training mode offered the opportunity to conduct scientific sampling. While sampling time was limited, we aimed to include diverse measurement types (e.g., CTD rosette profile, multicore collection, brief drifter deployment) for three reasons: (1) to help people gain confidence managing deployments, including required communication with vessel personnel; (2) to show them what was needed for sampling types outside of their specialties in order to broaden their perspectives as chief scientists; and (3) where possible, provide a small amount of seed data for new proposals (Figure 2). In 2023, we had just 24 hours of formal science time scheduled but managed to collect measurements at seven stations throughout the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea and conduct one small-boat deployment. In 2024, we had over one week of science time and collected measurements at multiple stations along each of three transects in the Bering Strait and Chukchi Sea regions. We also worked with NOAA National Ocean Service mapping team members onboard USCGC Healy in 2024 to conduct opportunistic mapping between transects and at night, which proved to be an excellent partnership in terms of data collection and training for early career researchers.

During vessel transits between stations, we found opportunities to hold additional trainings with onboard experts as a third mode of training (see Table 1). These sessions involved walkthroughs on the use of science equipment and/or short presentations with follow-on discussions or question and answer sessions. We used these trainings as opportunities to deepen participants’ knowledge base about science operations that might be outside the scope of their own work, to help them understand the broader social and human dimensions of Arctic science, and to stress the importance of communicating clearly with marine technicians, those working in shoreside support, and vessel crew in all aspects of cruise planning and at-sea operations. We also stressed the importance of post-cruise assessments for documenting successes and challenges of each cruise.

The fourth training modality involved building collaboration among the cohort. This was achieved informally through the camaraderie of the at-sea experience as well as formally through targeted research collaboration and proposal development discussions while onboard. Prior chief scientist training programs have had a range of scientific foci, including multidisciplinary oceanography (Reimers and Alberts, 2012), biological and chemical oceanography, or programs focused on facilities and tools for scientific seabed sediment sampling. The regional focus and interdisciplinary nature of the polar science training described here strongly supports network development critical for the success of US Arctic research, which is naturally interdisciplinary given limited vessel access and pressing science questions that require interdisciplinary approaches.

Program Practicalities

Securing Vessel Time

For these polar-focused cruises, we took a different approach compared to previous lower-latitude chief scientist training cruises that have often involved dedicated ship time requests. Polar vessels (i.e., icebreakers and ice-capable vessels) are in relatively short supply, and their operating seasons are limited in length. Thus, instead of requesting a week or more of dedicated ship time for the training activity, we requested opportunistic time on transits and an additional 24 hours for science operations. This model is also more cost-effective for agencies like NSF that fund training, as they already provide some support for transits.

Our 2023 request yielded a six-day cruise on R/V Sikuliaq between Seward and Nome, Alaska, in early June, at a time when the vessel was already transiting north to serve summer cruises in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. The 2024 request resulted in scheduling of a 15-day cruise on USCGC Healy through the Northwest Passage in August, which fit within the preexisting plans of the US Coast Guard to serve other trans-polar missions and duties. In each case, approximately 24 hours was allotted for dedicated, over-the-side, sampling-type operations in support of the training program.

While 24 hours does not seem like very much time for sampling training, this model worked surprisingly well, allowing ample time for meetings, discussions, and technical presentations. In 2023, the 24 hours of science (divided throughout all of the days at sea) provided just enough time to conduct approximately seven stations and one small-boat deployment that covered a variety of sampling modes. It also meant that we did not have a strong burden to conduct around-the-clock operations, so we could keep everyone on the same daytime shift, which was helpful for having whole-group training discussions.

It is worth noting that in 2024, the planned Northwest Passage cruise was canceled a few days in advance of sailing due to a vessel mechanical problem. After some repairs, we were able to regroup and take advantage of a unique opportunity provided by the US Coast Guard and NSF to conduct a ~10-day makeup cruise in the Chukchi Sea in October. The majority of that ship time was allotted for our training program, so we were able to host a more “traditional” training cruise with participants practicing their chief scientist skills through the management of a more realistic number of stations and shift work. The October timing of the cruise also meant that participants had to adapt their plans to account for fall-season storms and sea ice conditions.

The main challenge presented by requesting “cruises of opportunity” (i.e., transits) to support training is that the cruise planning timelines are often compressed into the months after the primary ship schedules have been established. The limited planning times available for the 2023 and 2024 training cruises required accelerated permitting and cruise planning and limited the degree to which participants could be involved in cruise planning as a training tool (especially in the case of the planned 2024 international cruise where foreign clearances were required). These short timelines also reduced the applicant pool due to preexisting conflicts (e.g., a large sea ice conference that happened in June 2023). Scheduling these types of training cruises with more lead time would allow for a longer advertising and recruitment period, reduce barriers to entry in the form of scheduling conflicts, and allow more time to engage participants in the full pre-cruise planning and permitting process.

Selection Process

The training program was advertised broadly through early career and professional society listservs, including national geoscience organizations like the American Geophysical Union (AGU); such polar listservs as those for the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS), the Polar Science Early Career Community Office (PSECCO), the Arctic Research Community Consortium of the United States (ARCUS), and the US Arctic Research Commission (USARC); and agency-related communities like the UNOLS mailing list group. Application questions addressed:

- Current and/or near-future eligibility to apply for US federal seagoing research grants

- A brief statement of interest, including past seagoing experience (if applicable), specific Arctic research interests, and ways that this program would be a career benefit

- Measurements or instrumentation of interest that could be explored during the cruise to provide education and/or seed data for new proposals

- Time frame of availability for a multi-day or multi-week cruise

We received 54 applications in 2023 and 68 in 2024, underscoring the high level of interest in the early career polar oceanographic community (especially in light of the short lead time for both programs). The aggregated applicants from both years represented 62 universities and 11 federal agencies or other organizations. Because of this high level of interest, prioritizing applications was a difficult process. The applications were anonymized and reviewed by a panel including the principal investigators, NSF program managers, and (in 2024) a representative from the US Coast Guard.

Ultimately, we leaned on the core goals of the program that we had shaped in collaboration with NSF program managers: To train the next generation of polar oceanographers in order to help them overcome barriers to entry for requesting and utilizing polar ship time, and write competitive and fundable proposals including ship-time requests to federal funding agencies. These criteria led us to prioritize (1) people who were currently eligible to submit US federal research grants (or could demonstrate that they would soon be eligible, for example, by having a faculty job offer in the United States), and (2) people who had a demonstrated and vested interest in Arctic and/or polar science. As a result, graduate students were given a lower priority because of the high number of applications from junior faculty and postdoctoral scholars, who are generally more ready (and more eligible) to submit proposals. International applicants were generally excluded on this basis as well, though we were glad to see international interest (see last section on Looking to the Future for future recommendations). Applicants who had no prior polar experience or detailed polar research questions were also given lower priority. In this vein, we recognize that our 2023 program was offered after a hiatus in early career chief scientist training cruises, and applicants who work outside polar regions likely applied to this Arctic/polar program as it was the only offering available at the time. We were sensitive to a need to help open doors to Arctic research and avoid “gatekeeping” for people who had not previously had opportunities to work in polar regions as graduate students, and/or those who did not have a strong polar research network. Ultimately, lack of prior polar experience was not a firm criterion. We leaned on applicants’ ability to articulate clear and practical scientific questions they would explore and the novel research tools they would apply.

We admitted 14 people in 2023 and 20 in 2024, including primarily junior faculty and postdoctoral scholars, as well as a few research faculty and senior graduate students. Participants represented 24 universities and one federal agency (NOAA), giving the program a broad reach beyond traditional oceanographic research hubs. Selected applicants spanned a diverse array of subspecialties within the major disciplinary groups (physical, chemical, and biological oceanography and marine geology): paleoclimate, benthic ecology, microbial ecology, chemical tracers, trace metal biogeochemistry, biophysical interactions, ocean circulation, marine mammal ecology and acoustics, air-sea interactions, continental shelf sediment dynamics, and marine technology. Because our program aimed to help expand participants’ professional networks, we organized shipboard discussions to foster interdisciplinary thinking and new proposal development.

Outcomes

We informally evaluated the outcomes of our training program by conducting post-program surveys in 2023 and 2024. Feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with participants commenting that the value of the program often exceeded expectations and indicating that the program addressed the concerns presented in Figure 1.

With regard to the overall experience, feedback included comments that “[t]his experience has made me feel far more confident in how to approach proposing and carrying out Arctic research,” and “this experience hit the right balance of informational sessions and time to actively learn skills via being chief scientist/fieldwork/etc.” This speaks to one of the major motivations for offering this program, namely, that graduate students and early career professionals rarely receive specific training regarding the leadership aspects of requesting and utilizing time on icebreakers and ice-capable vessels to do polar work. Several participants noted that serving as chief scientist for a day (or two) was one of the most valuable parts of the experience, even if it felt uncomfortable at times. By filling this role, they had the opportunity to see the wide range of responsibilities that a chief scientist must juggle and to gain confidence in coordinating with ship officers and crew to make safe and effective use of resources.

On the topic of using technical systems, one participant noted appreciating “the time and training from the science techs—their demonstrations were really useful for understanding how the onboard systems operate and will help me in leveraging resources to initiate better science.” Another said “[a] key takeaway was…deeper understanding of the [R/V] Sikuliaq’s systems and technical considerations you should have when designing a research cruise.” Technical presentations included information about ice sampling equipment, different types of winches, digital logging applications, etc. On the topic of ice forecasting, one participant expressed appreciation for the science operations manager’s connecting the trainees to various data streams (e.g., from bowcams and sensors), providing underway ice reports, and adding them to an email thread with the shoreside National Ice Center Analyst.

On the social side, we received feedback that “I also have a better sense of resources for more intentional and thoughtful community engagement.” Participants were also highly appreciative of the opportunity to sail with a community observer who was fully engaged with the training program. For example, we sailed with Lloyd Pikok Jr. from UIC Science/Battelle-Arctic Research Operations in 2023, and one respondent noted, “I think one of the main things I will take from this experience is Lloyd’s presence and thoughtful advice during the cruise. I appreciated his presentation on Indigenous knowledge, the resources he provided for leading sustainable and equitable partnerships with Indigenous communities, and his willingness to answer our/my questions.” By engaging an observer in the training program, we hoped to break down real or perceived barriers in communicating with local communities regularly during the cruise.

Participants also shared positive outcomes regarding their ability to manage interpersonal dynamics. For example, one noted that, “[w]e talked a lot about having someone on shore to talk with while being a chief sci/leading a team, and I can imagine reaching out to my fellow participants if I need someone to talk through an issue with while underway.” Throughout the experience, we discussed ways that a chief scientist can reach out to others for support, including ship officers and mentors on shore, in order to help manage conflicts or difficulties at sea.

Another positive, and perhaps unexpected, outcome was the development of a strong polar science cohort as a result of the program. This cohort seemed to provide an important support structure that significantly increased participant confidence in interdisciplinary use of ship time while also opening doors to new research collaborations that would have lasting impact on participants’ careers. We heard that “[i]t was a fun learning experience to be co-chief scientist with a colleague from another university and different research field” and “[w]hile a breadth of colleagues is to be expected on any research cruise, this was wholly unique in that we were all at similar career stages, eager to share best practices, and willing to think broadly about future collaboration.” Others said that “[t]he connections made on this cruise will lead to the submission of multiple proposals and will provide a cohort for networking throughout my career,” and “I had never worked with anyone on the cruise before and now see them as a core part of my Arctic research network.”

While our post-program surveys hint at program impact, the ultimate metric of success of the program will be increased proposal submissions, funding success, and executed seagoing science initiated by our participants. While only a little time has elapsed since our training efforts, we are informally aware of several collaborative proposals requesting ship time that have already been submitted as a result of the seed data or collaborative opportunities afforded by these two training efforts. We will continue to track proposal submissions, funded proposals, and other metrics of program success through future participant surveys.

Looking to the Future: Lessons Learned and Recommendations

Given the clear value of this training program for professional development of early career scientists (junior faculty, postdocs, and senior graduate students), we recommend similar polar-specific training be offered at regular intervals in the future (at least every two to three years) to maintain a deep bench of polar scientists to lead the next generation of cutting-edge field research programs. We received 122 applications in 2023–2024 and were able to serve approximately 34 people. This large application response was surprising, given the short lead time to plan around other commitments like teaching, other fieldwork, and conferences. In the time since, we have continued to receive multiple inquiries from early career researchers asking if the program will be offered again. Thus, there is an obvious appetite for this type of training among the research community. Meanwhile, the potential pool of early career applicants continues to grow as students complete their degrees. Ensuring the next generation of emerging polar scientists has access to these important leadership and soft skill development opportunities is key to ensuring a vibrant and innovative polar science community in the future.

In terms of practicalities for making similar trainings cost-effective, we encourage researchers and funding agencies to consider leveraging vessel transits or piggybacking training efforts on other funded cruises with high potential for synergy. “Dead-head” transits to move vessels between ports are routine, and using these for training programs, with even a modest allotment of science operational time (~24 hours), can provide ideal “cruises of opportunity” and allow a surprisingly useful amount of hands-on training mixed with focused workshop-style training. The potential for participants to obtain seed data is admittedly more limited on cruises that are primarily transits, but we have found that the experience still sparks many research ideas and collaborations for new proposals. Additionally, the time commitment of a one-week transit is easier for busy junior faculty juggling a host of new commitments than a multi-week cruise to a remote location. Alternatively, sharing ship time with other science groups, such as our partnering with NOAA scientists conducting seafloor mapping on our 2024 cruise, can result in remarkable synergies. Though this may require a prolonged time at sea for junior scientists, it has the potential to enhance seed data collection and expand mentorship and personal network development at sea.

While virtual programs without a seagoing component would allow us to accommodate more participants, we strongly encourage trainings that give early career participants practical experience “in the driver’s seat” as acting chief scientists. In our program, we found that this immersive part of the training highlights difficulties and strategies that are hard to absorb in any other way. Indeed, many of the comments received from participants identified the immersive at sea experience and the cohesion built with peers (which is also facilitated by an in-person experience) as central to their improved confidence.

We see strong potential for an international collaborative training effort, although the national-level funding realities have to date made this challenging. We received interest in both years from researchers in countries that have strong polar research programs, but we were not able to accept these applications due to the eligibility constraint of serving applicants who could apply for US federal research grants. We recommend that mechanisms for joint international funding of ship time and participant support be explored. Offering a joint international program in the future (and bringing on foreign co-investigators as mentors) would serve to build an even stronger international and interdisciplinary cohort of early career polar oceanographers.

Lastly, “training” typically connotes mentorship by organizers and senior scientists akin to the typical graduate school apprenticeship model; however, much of the impact of this training program was facilitated by the peer-to-peer (and near-peer) mentoring networks that formed during the workshops and cruises. The peer mentoring structure in the acting chief scientist role helped participants learn to lean on each other as well as mentors for advice. This model thus ensures that the relatively modest investment in resources and personnel time continues to pay off as participants become established in their research careers. Those trained in this program are also likely to share experiences and knowledge gained to a distributed network of their own peers outside the training group, ensuring a multiplier effect within the broader science community. Thus, training early career polar scientists to embrace leadership opportunities seems to be most effective when we simultaneously facilitate supportive communities of peers along with an expanded network of mentors.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NSF grants OPP 2303606 and 2401176. We thank the captains, crew, marine technicians, and community observers on R/V Sikuliaq (2023) and USCGC Healy (2024) for their support of these training efforts, with special acknowledgment to CAPT J. Hamill on Sikuliaq and CAPT M. Schallip, LCDR A. Hamel, and ENS. K. Gower on Healy. Marine technicians Ethan Roth, Emily Shimada, Brandon D’Andrea, and Chris Fanshier contributed substantially to the success of this program by sharing their time and expertise at sea. We thank all the guest presenters and mentors who participated in the workshops and at sea. We thank the Hamlet of Kugluktuk in Nunavut, Canada, for their generosity in accommodating a planned personnel transfer and supporting a community event in summer 2024. Finally, we thank the 34 participants who brought their energy and ideas to the program and developed robust collaborative relationships.