Introduction

In 2018, a group of researchers and program officers convened a working group at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, to discuss the state of the field of marine mycology and how we wanted to envision its future. Outputs of that meeting (Amend et al., 2019; Gladfelter et al., 2019) established a baseline for the state of the field, and we drafted a wish list of technological and programmatic breakthroughs, aiming to achieve parity with other marine microbial domains where there had been something of a renaissance in the previous decade. In 2024, a similar, and partially overlapping group, convened on the opposite coast of North America, in Asilomar, California, to assess our collective successes and to prioritize opportunities for the future of the field. The meeting preceded the biennial 32nd Fungal Genetics Conference, and our group, on the whole, was more steeped in mycology than in oceanography. For this reason, we opted to publish our meeting results in this journal in order to reach those oceanographers who don’t typically read articles in fungal biology journals.

Pressing Questions in Marine Mycology and How to Answer Them

The primary component of the meeting was a group think-pair-share about pressing questions in marine mycology, the impediments that historically inhibited progress on answering these questions, and ways to overcome those obstacles. Together, we outlined the most urgent and aspirational questions facing our field. Answering these questions will inform understanding of marine fungal biology, ecology, and evolution, while progressing toward increased inclusion of fungi in oceanographic and climate science world views. Answers achieved will also serve as important milestones by which to gauge our progress at the next marine mycology working group gathering.

Question 1. What is a Marine Fungus?

One of the greatest challenges to studying marine fungi is in defining the field, a task more complex than first impressions might imply. For most organisms, including plants, animals, bacteria, and archaea, the shoreline represents a nearly immutable evolutionary Rubicon that is crossed infrequently, resulting in deeply diverging lineages that can clearly be distinguished as marine or terrestrial. Among fungi, some species are also obligately marine and possess specialized traits such as appendages that enable buoyancy or motility (Figure 1). However, many fungi inhabiting the ocean are seemingly indistinguishable from terrestrial taxa and are putatively amphibious (El Baidouri et al., 2021), owing perhaps to thick cell walls and a panoply of adaptations supporting wide ecological amplitudes, such as wide variation in osmotic potential. In the absence of phylogenetic or situational circumscriptions of marine fungi, the field has instead relied on an operational definition: a marine fungus is one that commonly occurs, forages, reproduces, engages in symbioses in, and/or is adapted to the ocean (paraphrased from Pang et al., 2016).

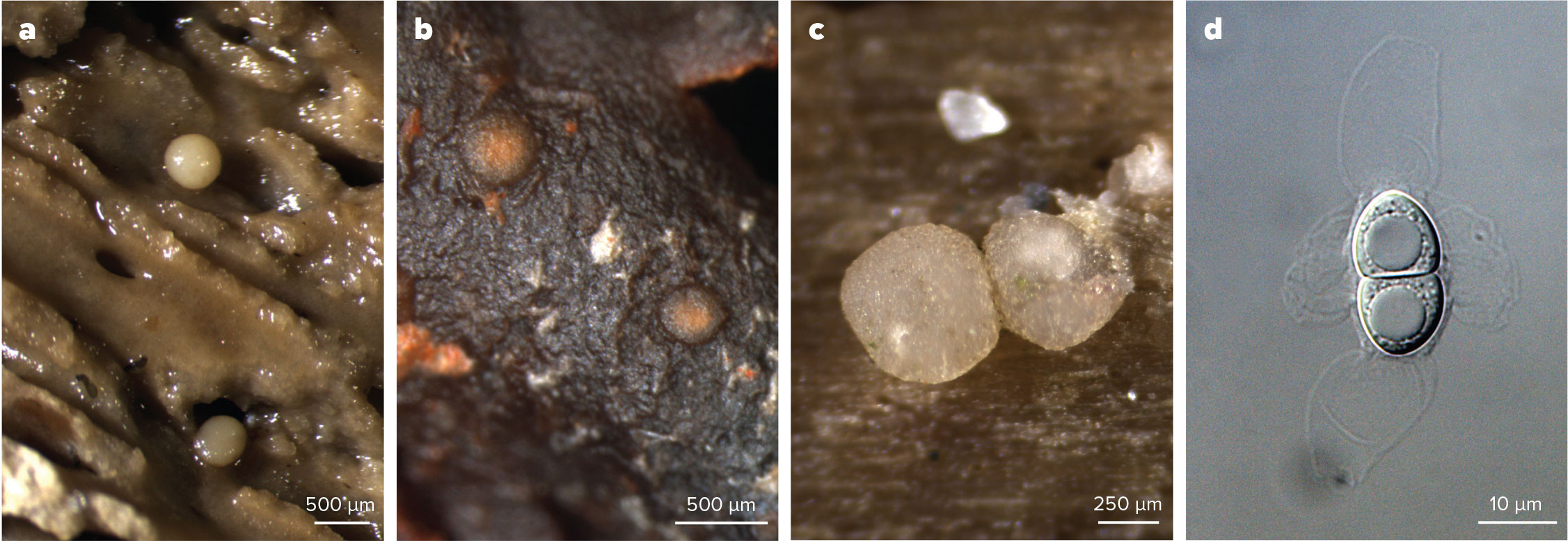

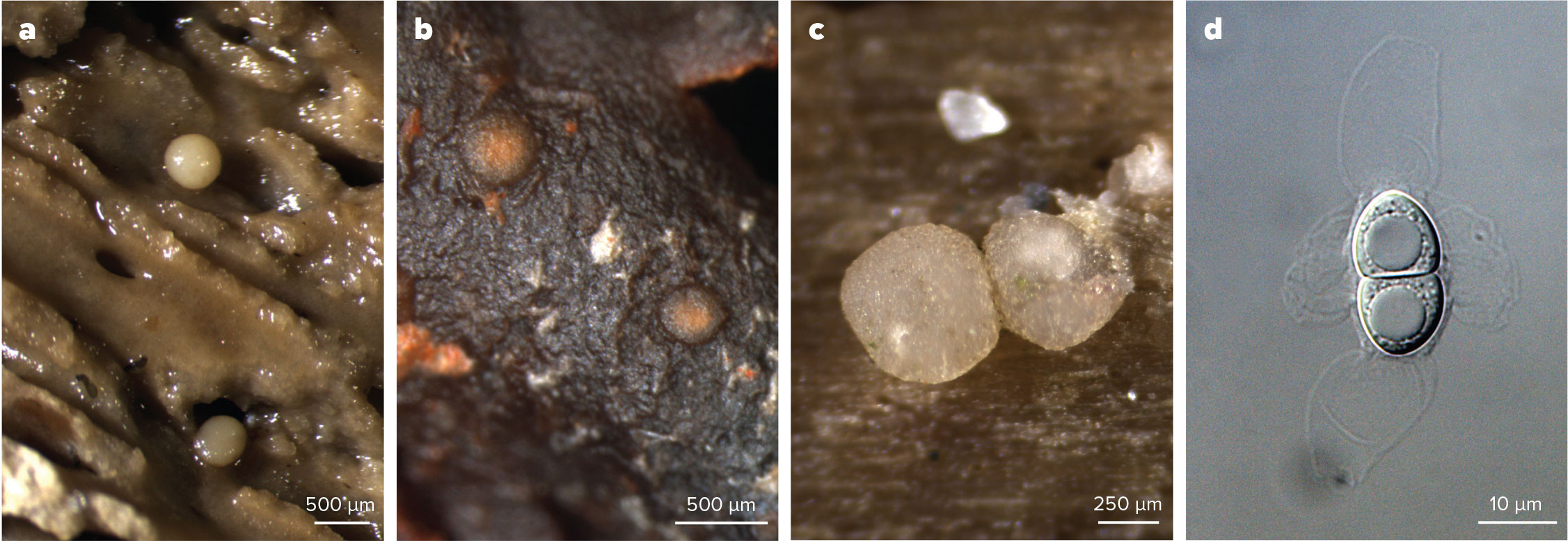

FIGURE 1. Marine fungi are shown on different marine substrates: (a) two gasteromycetous basidiomata of a Nia (Agaricales, Agaricomycetes, Basidiomycota) species on whale bone, (b) two apothecia of Calycina marina (Helotiales, Leotiomycetes, Ascomycota) on decaying brown alga, and (c) two cleistothecia of Amylocarpus encephaloides (Helotiales, Leotiomycetes, Ascomycota) on intertidal wood. (d) An ascospore of Lautisporopsis circumvestita (Microascales, Sordariomycetes, Ascomycota) exhibits a gelatinous sheath and appendages. Photo credits: Teppo Rämä, UiT The Arctic University of Norway. > High res figure

|

Very few marine fungi produce macroscopic structures in the wild, so tracking the metabolic and reproductive activity of microorganisms in order to meet this burden of proof is challenging, if not impossible, in a typical observational study. This makes it difficult to distinguish marine residents from those that recently dispersed from terrestrial habitats, particularly in nearshore sites where terrestrial inputs are plausible and expected. This definition also excludes alternative and more complicated life-cycle scenarios. What if fungi reproduce in a non-marine habitat but metabolize marine organic matter (like a microbial salmon)? What if fungi reproduce in the ocean but disperse into non-marine habitats (like a microbial Anguilla eel)? These unanswered questions have dampened the impact of marine fungal research because the ambiguous ecology involved provides convenient cover for dismissing the vast majority of community members as transient tourists with little to no function.

This challenge might be overcome by leveraging a combination of technology, creative experimentation, and novel conceptual frameworks. For example, fungal source tracking using tools from population genomics or genetic mark-recapture might inform the rate and prevalence of land-sea dispersal in natural habitats. These observations could be augmented with experimental approaches that limit or facilitate dispersal in controlled settings (see Grossart et al. 2010, for an example using bacteria). Substrate labeling techniques, including isotopes or quantum dots, might also shine light on fungal community members that are actively metabolizing organic matter (e.g., Orsi et al., 2022). Life cycles, including reproduction, might be illuminated by a greater effort to observe them in nature or by experimental induction in microcosms. We can also take cues from transcriptomic analyses of marine fungi, particularly those that are far from terrestrial inputs. Finally, marine mycology might overcome this limiting definition by embracing the idea that fungi exist in metacommunities that extend beyond habitats circumscribed by other, less plastic, organisms (e.g., Wainwright et al., 2017).

Question 2. What Determines the Diversity, Distribution, and Dispersal of Marine Fungi?

Several open questions related to marine fungal community ecology are important to answer in order to begin to understand the functions of fungi in the marine ecosystem. First, despite the recent opportunities afforded by wide availability of DNA sequencing, we have barely improved our understanding of marine fungal diversity (whether regarding richness, evenness, abundance, biomass, phylogenetic, functional, or other) compared to the era before this technological innovation (Cunliffe, 2023). Second, while some efforts are underway to investigate the biogeography of these fungi using culture-independent approaches (e.g., Wainwright et al., 2018; Ettinger et al., 2021), we still have much to learn about their spatial and temporal variation and how abiotic and biotic factors might affect their distribution. For example, does marine fungal diversity change over geographic distance? with ocean currents, depth, salinity, or seasonality? among habitats with different anthropogenic inputs? Finally, there are tremendous opportunities to discover the mechanisms by which these fungi assemble into their marine niches and the parameters that influence their dispersal.

While we can make predictions about marine fungi based on information about their terrestrial counterparts, the lack of foundational knowledge regarding marine fungal diversity, distribution, and dispersal is compounded by methodological limitations and a lack of replication and standardization. A fundamental barrier lies in the absence of targeted exploration: fungi remain largely overlooked in studies of marine microbiology, particularly in those using omics-based approaches. One reason for this lack of attention is the difficulty in obtaining meaningful taxonomic and functional assignments from fungal nucleotide sequences. Current environmental genomic and transcriptomic databases are deficient in fungal representation, especially for marine fungi, which often leads to poor annotations (Gabaldón, 2020). This gap creates a negative feedback loop by disincentivizing a focus by the microbiological or oceanographic communities on fungi, because these analyses will contain degrees of uncertainty or sparsity that impede quick and easy analysis or publication. Although public datasets of marine metagenomes contain fungal reads, they are not readily processed using standard pipelines and parameters, making it difficult for those with an interest in marine fungi to glean useful information from such data. Further, there is not yet a consensus on field, laboratory, or bioinformatic methods, making the few studies that do exist difficult to compare with each other.

To address these questions of diversity and distribution, it is essential that we begin to make standardized, replicated, and targeted observations across space and time at a variety of scales. Improved genomic resources will greatly facilitate this line of work, enabling future and past omics surveys to reveal fungal diversity. Future studies should attempt to follow standardized methods for sample collection, DNA extraction, and sequencing to create a global-scale image of fungal diversity out of regional datasets. We suggest three steps to enable large-scale biodiversity research: (1) build marine fungal genetic databases through characterization and sequencing of fungal isolates from a variety of marine habitats; (2) develop and distribute a series of best practices for field, lab, and computational methods that promote FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable) data practices (Wilkinson et al., 2016); (3) use these resources and methods to perform targeted observations of marine fungal communities across temporal and environmental gradients or to test hypotheses about their community assembly and dispersal.

Question 3. What Are the Active Roles Fungi Play in Symbiotic Association with Other Marine Organisms?

Fungi are present in and on every marine host organism researchers have investigated, including sessile invertebrates, primary producers, and large fish and mammals. Despite the ubiquity of fungi in and on living hosts, we have yet to determine where these interactions fall on the mutualism-parasitism continuum, and the extent to which these interactions are obligate and/or specific on the part of the fungi or the host. Although the majority of the effort thus far has enumerated fungal presence in phytoplankton (discussed below), marine invertebrate (Yarden, 2014) and macrophyte (Ettinger et al., 2020) interactions with other organisms, including bacteria (Steffan et al., 2020) and viruses (Urayama et al., 2024), are also likely to occur among marine fungi.

These interactions, however, remain largely unaddressed due to lack of initiative alongside technical hurdles linked to studying complex marine holobionts. Though it is comparatively easy, for example, to design bacteria-specific primers that won’t co-amplify host DNA, or to use selective depletion methods (such as Poly-A capture) to enrich for non-eukaryotic nucleic acids, these techniques tend to be ineffective for fungi given their comparatively recent evolutionary divergence from their hosts. This precludes fungi from inclusion in the early “discovery” phases of symbiosis research from which more specific and mechanistic hypotheses can arise. Research into fungal roles in marine symbioses is further impeded by a lack of suitable model systems that are easily manipulated and for which genetic and imaging tools are readily available.

Several approaches can be harnessed to shed light on these associations. In addition to identifying the players involved (fungi and eukaryote/prokaryote/viral associates), comparative transcriptomics and metabolomics are powerful tools for defining fungal activity as either free life forms or as symbionts with other marine organisms (Breyer et al., 2022; Orsi et al., 2022). These analyses can be followed by hypothesis-driven experiments that involve manipulation of the systems in question. Curing marine-derived fungi of bacteria or viruses or altering the diversity or genetic nature of these associates may provide insights into their physiological and ecological significance (Clancey et al., 2020). Experiments employing inoculation or depletion of fungal components in marine holobionts may provide another means for advancing our understanding of the importance of fungi in marine niches. The incorporation of genetics, cell biology, analytical and synthetic chemistry, imaging, and sophisticated cultivation will be key to understanding mechanisms of the observed phenomena. Initial studies may be limited to reductionist/simple approaches, although even “simple” interactions may include more than two partners (Márquez et al., 2007). Nonetheless, understanding the roles marine fungi play in less complex symbiotic relationships may provide a first and crucial step toward appreciating their potential ecological functions, evolution and co-evolution with interacting partners, and contribution to the health and fitness of other marine life forms. Progress in establishing model or reference systems (Shikina et al., 2023, and references within) that can be monitored and subject to manipulation under laboratory conditions will be essential in order to provide the platforms for such studies and to potentially leverage those developed to study other microbial interactions.

Question 4. What Do Fungi Contribute to the Marine Carbon Cycling Loop?

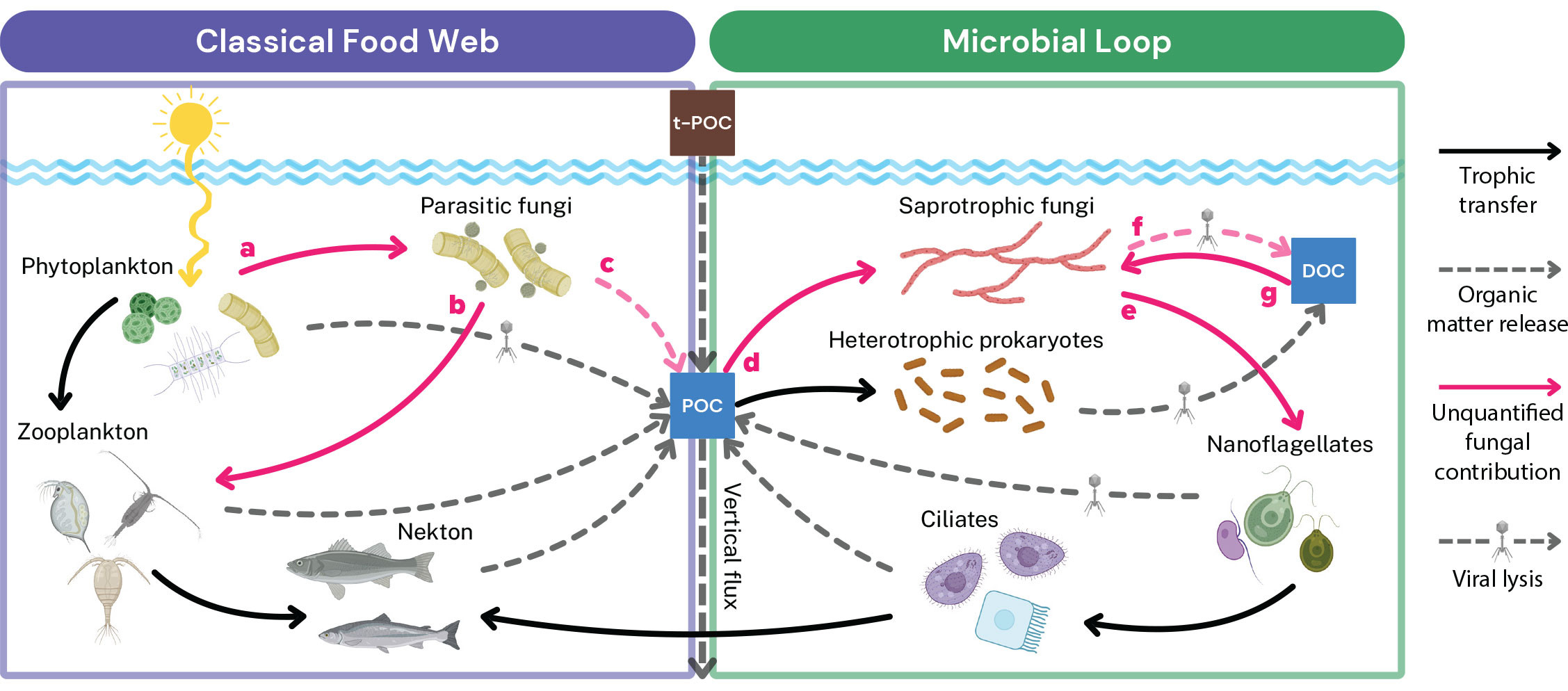

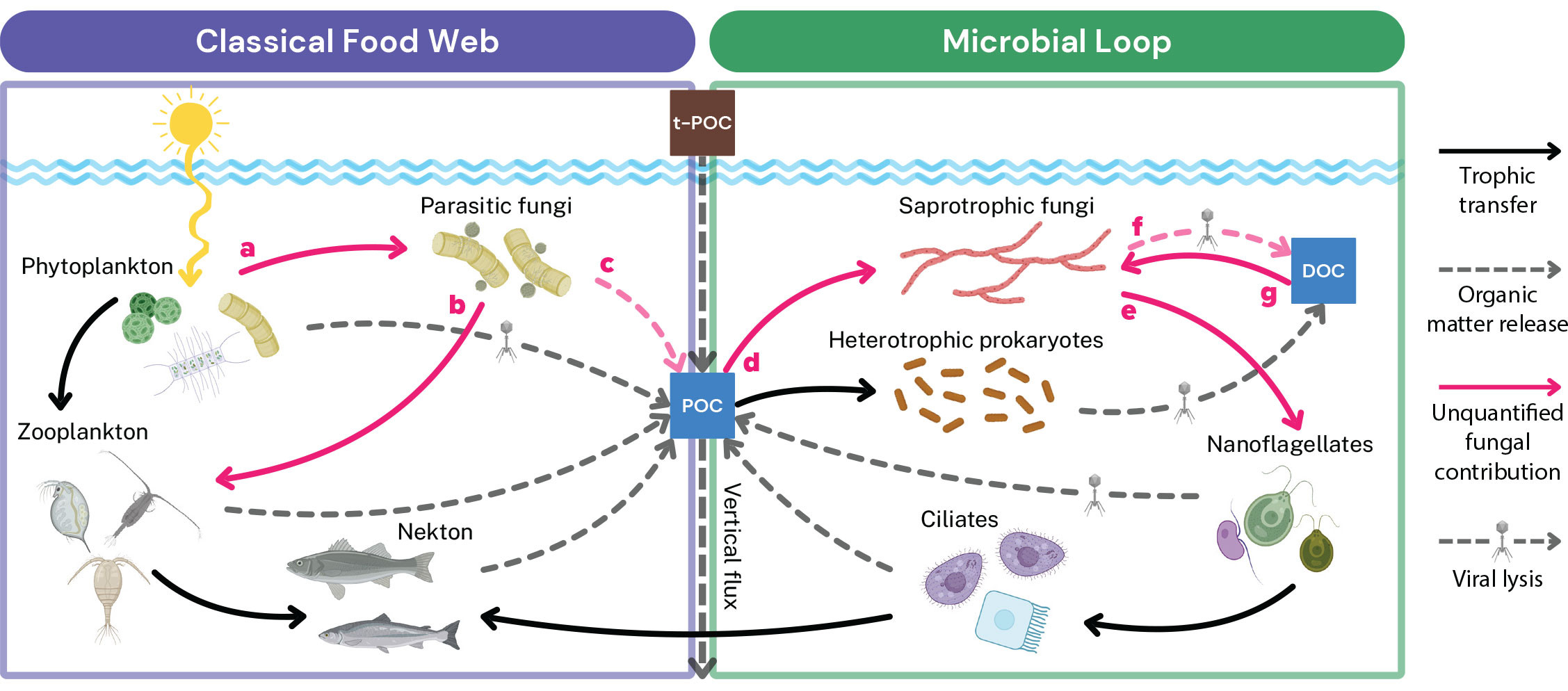

Dominant models of the ocean’s microbial loop show bacteria (and, to a lesser extent, archaea and viruses) as the major recyclers of dissolved organic matter and agents of carbon transfer to the higher planktonic trophic levels (Azam, 1998; Suttle, 2005). Although fungi are known to play a role in the degradation of marine organic matter (Kagami et al., 2014; Amend et al., 2019), their contributions to carbon transformation and trophic transfer remain poorly studied compared with those of their prokaryotic counterparts. Nevertheless, fungi are degraders of organic macromolecules in the marine ecosystem (Gutiérrez et al., 2011), and through parasitism on primary producers, they can transfer carbon to higher trophic levels and release dissolved and particulate organic matter (Klawonn et al., 2021), a role more commonly attributed to viruses. Multiple overlooked fungal carbon cycling pathways have potential implications for the rate of carbon transfer between the primary reservoirs and fractions of organic matter in marine environments (Figure 2).

One fundamental reason we lack these insights is the absence of standardized methods for quantifying the contributions of marine fungi to organic matter processing, microbial secondary production, or carbon respiration. While protocols exist to measure secondary production and respiration in marine bacteria using radioactively labeled substrates, such as leucine (Simon and Azam, 1989), or in archaea using labeled molecules combined with specific inhibitors (Levipan et al., 2007), no such methodologies exist for fungi. An additional challenge is the lack of studies analyzing the trophic interactions of saprotrophic and parasitic fungi in marine environments. These interactions introduce nuances that, when unaccounted for, diminish the accuracy of carbon transfer models in planktonic trophic webs (Figure 2). There are few long-term data on fungal infections during phytoplankton blooms, even though phytoplankton population monitoring is common practice in oceanographic studies. Finally, we are challenged by a lack of model systems with which to explore the ecology and evolution of phytoplankton pathosystems. These unresolved questions in marine phycology exacerbate our lack of understanding of marine fungal infection dynamics and its consequences for marine carbon cycling in the ocean.

FIGURE 2. Conceptual model explaining the interactions of marine fungi in the classic and microbial trophic webs in pelagic environments. Unquantified routes for carbon transfer associated with fungi are highlighted (Munn and Munn, 2020). Parasitic fungi contribute to the release of particulate and dissolved organic matter by infecting phytoplankton (a), creating a conduit for trophic transfer of carbon to zooplankton via zoospore production (b). Through lysing host cells, parasitic fungi contribute to sinking aggregates and particles (c). Saprotrophic fungi are responsible for the degradation of coastal ecosystem organic matter derived from both terrestrial (t-POC) and marine sources, including particulate (POC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (d). Saprotrophic fungi degrade DOC, mainly by processing the fraction of semi-labile to refractory macromolecules (HMW-DOC) via specialized extracellular enzymes. Through enzymatic activity and potential viral lysis, saprotrophic fungi contribute to DOC pools (f). Modifying the particulate fraction of organic matter can influence vertical flux and, thus, the functioning of the biological carbon pump. Finally, both parasitic and saprotrophic fungi are grazed by higher trophic levels (e.g., zooplankton and nanoflagellates), contributing to higher trophic transfer (e, b). POC = Particulate organic carbon. DOC = Dissolved organic carbon. Figure compiled in https://BioRender.com. > High res figure

|

The first step for quantifying the fungal contribution to carbon degradation and transfer would be to identify the substrate preferences of saprotrophic fungi in different environments and under variable oceanographic conditions. Quantitative degradation assays that include different fractions of organic matter (particulate and dissolved, POM and DOM, respectively) from variable sources (e.g., in terms of composition, C:N ratios, and stable isotope signature) will help us to understand the mechanisms and rates of fungal modification of organic matter. Such studies should leverage novel and standardized methods to quantify fungal uptake of DOM, secondary production, and respiration. These could be modifications of methodologies that are used for freshwater or soil fungi to measure fungal production. Stable isotope probing is a method used to investigate fungal capacities to degrade DOM and could be leveraged to help understand fungal activity across varying conditions, including their interaction with other taxonomic groups in the marine environment (Fabian et al., 2017; Orsi et al., 2022). The role of fungal parasitism in carbon cycling might be better understood through more rigorous monitoring, including using traditional microscopic techniques alongside new methods (e.g., flow imaging cytometry), to estimate infection prevalence. Coupling these observations with molecular, culture-, and lab-based approaches will facilitate an understanding of the parasitic life cycle and its impacts on host dynamics and organic matter release.

Question 5. To What Extent Do Fungi Participate in the Biological Carbon Pump?

The “biological carbon pump” controls the ocean’s carbon cycle by vertically transporting organic carbon from the surface into the deep sea via sinking particles (Siegel et al., 2023). Most of these carbon-rich particles are consumed and respired before reaching the seafloor, and the depth they reach prior to remineralization determines the timescale over which carbon is sequestered in the deep ocean. The mechanisms controlling carbon flux attenuation in the ocean are largely unobserved and poorly modeled and have been the major focus of recent international field programs (e.g., NASA EXport Processes in the Ocean from RemoTe Sensing [EXPORTS], Controls Over Mesopelagic Interior Carbon Storage [COMICS], Assessing marine biogenic matter Production, Export, and Remineralization: from the surface to the dark Ocean [APERO]). Current models of particle flux attenuation focus on the roles that mesopelagic zooplankton and bacteria play in consuming and respiring sinking carbon and do not include marine fungi. Given the known importance of fungi in metabolizing organic material in both terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, it is likely that fungi also play a key role in degrading sinking particles in the marine system (Bochdansky et al., 2017; Chrismas and Cunliffe, 2020). Indeed, the ability of fungi to form hyphal mats make them potentially both important architectural elements of particles as well as resistant to degradation that could promote persistence in the water column and in deeper deposition of carbon.

One reason that almost no observations exist of fungi on marine particles is that fungi are not included in traditional conceptual frameworks that describe the biological pump (e.g., Iversen, 2023). Detecting fungal diversity and metabolism within sinking particles and quantifying their role in particle remineralization require studies specifically designed to target these organisms and the expertise to recognize their potential importance. Currently, oceanographers who have ready access to sinking particles are unlikely to have the expertise to detect or recognize fungi in their samples. Similarly, mycologists with terrestrial research backgrounds are less familiar with the major ecological and biogeochemical questions in oceanography or the standard tools and resources used to address such inquiries. Therefore, bridging this gap will require a purposeful effort toward interdisciplinary collaboration. Methodological and technical obstacles presented by collection of particles also pose significant challenges for the study of marine fungi in such environments. Because collecting particles in pelagic systems is time-consuming and arduous, most research efforts primarily focus on the water column rather than on particles directly.

Adapting mycological practices to align with classic oceanographic techniques offers a promising approach to understanding fungal activity in marine environments. An easy and critical first step will be to compare preexisting, public datasets (e.g., Boeuf et al., 2019; Preston et al., 2020; Valencia et al., 2021; Durkin et al., 2022) with reference databases that are meaningfully populated with fungi. This will allow researchers to measure the relative abundance, and role, of fungi compared to other heterotrophs on particles and in the water column in situ. However, care must be taken to determine beforehand whether sample collection is inclusive of fungi (i.e., filter size). Conducting manipulation experiments (both at sea and within controlled laboratory settings) that incorporate spatiotemporal aspects of particle decomposition and sedimentation could also provide valuable information on the role of fungi in the biological carbon pump. Depth-related studies could identify where within the water column fungi are most active on sinking particles, whereas temporal studies can address fungal taxonomic and metabolic succession as particle decomposition occurs. Another potential method would be to leverage respiration traps (Boyd et al., 2015) to assess oxygen depletion attributable to fungal respiration. However, distinguishing between fungal and other heterotrophic activity remains a major challenge that must be addressed in method development.

Question 6. How Will the Anthropocene Impact Marine Fungi?

The Anthropocene, driven by human-induced factors such as acidification, warming, pollution, and extreme weather events, could have profound impacts on marine mycological diversity, distribution, and evolution (Kumar et al., 2021). These stressors could simultaneously diminish some fungal diversity through habitat loss and environmental degradation, while promoting opportunistic colonization of new habitats and hosts. For example, plastic, a novel marine “habitat” whose expansion is outpacing coral biomass loss, might drive novel distributions and structures of fungal communities in areas of high deposition (Lacerda et al., 2020). Host organisms stressed by food-web modification, ocean warming, or acidification might become more susceptible to fungal pathogens in future climates. Finally, given fungi’s penchant for amphibious distributions, sea level rise may impact land-sea connectivity in ways that influence fungal dispersal and marine fungal composition. Long-term studies that capture change in fungal ecology are critically important (Chrismas et al., 2023).

Assessment of change at a global scale is hindered by the lack of a fungal baseline for comparison, and with a global surveillance program just starting (Fernandes et al., 2024), the true extent of impacts remains unclear. For example, there are no marine fungi currently listed on the ICUN Red List (Hickman and Atherton, 2024), and without some data on population trends, it is difficult to assess whether and how fungi are impacted. As stated elsewhere in this review, monitoring marine fungi is neither straightforward nor simple, so basic issues of sampling and database compilation will need to be resolved before meaningful monitoring can take place and be integrated with an understanding of cumulative effects of anthropogenic stressors and changing climate (Gissi et al., 2021). Manipulation experiments, in which various aspects of environmental change are simulated in order to measure fungal response, are also generally lacking, with some notable exceptions, although some more inclusive “holobiont” studies occasionally report fungal compositional changes (e.g., Thurber et al., 2009). Devising ecologically relevant experiments is challenging, again, without a reasonable understanding of fungal life cycles, distributions, and metacommunities. Yet, the importance of this task is exemplified by the likelihood of recent human fungal pathogen emergences, such as the global public health threat Candida auris, which has been isolated from marine environments and hypothesized to be harbored within human plastic waste (Akinbobola et al., 2024). Indeed, many marine-derived fungi show polyextremotolerance (Gostinčar et al., 2023), making their ability to exploit new niches opened by climate disruption simultaneously an opportunity and a threat.

To address these questions, interdisciplinary collaboration and long-term, continuous studies are essential. Establishing baseline sampling protocols and integrating ongoing measurements with sentinel site surveillance are crucial steps. If appropriate sampling and storage permits, it might be possible to go “back in time” by reanalyzing long-term datasets such as those collected by the Hawaii Ocean Time-series program or samples collected from marine Long-Term Ecological Research sites, or even from stratified substrates like sediments or ice sheets. Finally, fungal interactions with plastic will play an increasingly important role in both marine ecology and potential remediation.

Question 7. How Do Marine Fungal Genomes Differ from Those of Terrestrial Species?

Given the exceptional distribution of either amphibious species or those resulting from repeated evolutionary transitions between land and sea, a pressing question is whether and how genomes differ among organisms that live in these two habitats. On the one hand, given the myriad challenges an organism might face in an ocean habitat (salinity, hydrostatic pressure, negative buoyancy), one might expect genes that are consistently unique between these two habitats. On the other hand, the high frequency of habitat transitions might instead indicate innate plasticity and environmental tolerance that negates any evolutionary pressure per se.

In MycoCosm (Grigoriev et al., 2014) the largest repository of curated fungal genomes, only seven of 2,578 genomes are isolated from marine habitats (as of this writing). FungiDB (Basenko et al., 2024), another curated fungal database, contains three, including the black yeast Hortaea werneckii and two putative pathogens. The only planktonic fungus sequenced in Mycocosm, Rhodotorula sphaerocarpa, demonstrated a streamlined genome that was reduced by approximately 10% when compared to terrestrial Rhodotorula (Lane et al., 2023). The main divergences were in the reduction of transporter genes, while all core metabolisms are conserved. With only a single genome to compare to terrestrial counterparts, however, statistical and inferential power is limited. Further, none of the seven marine fungal genomes hosted on Mycocosm have a terrestrial conspecific genome also sequenced, so any understanding of genome divergence will suffer from distortions of phylogenetic distance.

Compared to most of the questions raised during our discussion, overcoming this barrier is particularly tractable and straightforward. We must sequence more fungal genomes and perform comparative analyses of them. One way to start is by compiling and distributing a list of “most wanted” taxa, backed by interest from national and international research agencies like the US Joint Genome Institute via the One Thousand Fungal Genomes Project, private agencies with active marine microbial programs (e.g., Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation or Simons Foundation), or industrial partners. As a starting place, it could be helpful to sequence the genomes of isolates already accessioned and maintained in large culture collections. As always, expanding the reach and capacity of existing and publicly accessible culture collections are critical to these efforts.

Question 8. How Can the Discovery of Marine Fungal Natural Products Be Improved and Expanded?

Marine fungi are prolific producers of new natural products and enzymes with the potential for novel applications (Carroll et al., 2024). Many of them are presumed to be endemic to marine habitats, as chemists estimate that around 71% of marine natural products are not expressed by organisms in terrestrial environments (Kamat et al., 2023). Secondary metabolites produced by marine fungi include steroids, polyketides, terpenes, peptides, and hybrid metabolites; they have diverse biological activities and potential applications as antimicrobial, antiviral, and anticancer agents, among others (Carroll et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024). However, the clinical development pipeline for marine fungal natural products is almost nonexistent. To our knowledge, only a single developed pharmaceutical exists: Plinabulin (NPI-2358), an antitumor agent, which is a semi-synthetic analogue of a natural product phenylahistin (synonym halimide) isolated from marine Aspergillus strains (Yamazaki et al., 2012), and which is currently in Phase 3 of clinical development. Nearly all fungi reported as sources of new natural compounds belong to a few common and easily isolated facultative marine Ascomycetes genera, like Aspergillus and Penicillium, whereas hardly any are reported from rarer obligately marine taxa (Overy et al., 2014; Imhoff, 2016; Carroll et al., 2021). Indeed, Carroll et al. (2021) reported that 70% of marine fungal natural products isolated before 2015 were structurally similar to those reported between 2015 and 2020, suggesting that there is an opportunity to improve the methods used to study marine fungal natural products, particularly from unexplored obligate marine fungi.

Isolating and culturing marine fungi is challenging and time consuming and is the single greatest challenge to realizing their full natural product chemistry potential. Because chemists rarely collaborate with marine mycologists, insufficient knowledge of isolation and culturing of obligate marine species has led to repeated reevaluation of the same ubiquitous ascomycetes. Knowledge of autecology plays a critical role in successful isolations, and these details are not easily gleaned from environmental omics studies (Rämä and Quandt, 2021). In fact, such knowledge is increasingly rare within marine mycology’s own ranks, and it is critical that transfer of knowledge of legacy literature, skills, and experience is passed on to emerging marine mycologists. Concurrently, better integration of culture-based methods with environmental omics approaches is crucial for a more holistic understanding of individual organisms, including their biosynthetic potential, potential metabolic deficiencies, and interactions with other organisms in situ.

By improving technology and increasing knowledge of marine fungal isolation techniques, new fungal diversity can be brought into culture and studied more efficiently for natural products. It is also important to note that there are several areas and ecological niches of marine fungi that remain understudied and are likely to yield interesting fungi and natural products. Further, we should develop ways to combine culturing-based approaches with metagenomics and genomics-enabled genome mining to predict the biosynthetic potential of individual species and help to prioritize the most interesting producers. Natural product chemists might also make the most of existing collections using the “one strain many compounds” approach, in which one strain grown under different environmental conditions produces different compounds. Silent biosynthetic gene clusters, or clusters from uncultivable fungi detected through sequencing can be expressed heterologously. While this technology has been applied in other systems, there is a need to develop marine fungal models. To this end, marine fungal natural product chemists should develop a framework for determining culturing conditions that optimize the titers of interesting natural products.

Question 9. What Are the Life Cycles, Morphologies, and Reproductive Strategies for Survival, Dispersal, and Success of Fungi in the Ocean?

Fungi in the terrestrial world have a variety of shapes and sizes, from unicellular yeasts to filamentous mycelia to majestic fruiting bodies. While we can’t say for certain that plasticity of shapes in the fungal kingdom is adaptive, it is reasonable to assume that the capacity to change shapes endows species with the capacity to cope with different conditions in the environment (Diver et al., 2024). Aquatic environments differ from terrestrial in fundamental ways. Challenges posed by the marine environment include the need for buoyancy and adaptation to salt fluctuations, UV exposure, high pressure, and often sparse substrates. It is unclear if marine-adapted fungi contain a similar array of shapes as is seen in the terrestrial environment or if marine conditions have led to additional and new innovations or variations in morphogenesis. One obvious example of distinct marine fungal morphology is the development of appendages to promote buoyancy and attachment of spores to substrates. What other innovations do marine fungi exhibit? Shape shifting in terrestrial fungi is often associated with mating/reproductive cycles and depends on small diffusible molecules sensed from neighboring cells. How might these small molecules function while avoiding dilution and degradation in the aquatic environment? Are marine fungi undergoing meiotic reproduction? And if so, how do gametes find partners? Because we do not yet know how the marine environment impacts fungi cell and developmental biology, we lack methods to detect life cycle events in situ.

Fungal morphologies and life cycles within marine habitats are little known for several reasons. First, except for on substrates rich in organic carbon, fungi tend to be sparse and small, making them difficult to observe in spatially and temporally patchy natural habitats. Although they display various morphologies when cultured, it is unclear whether these are representative of physiologies they display in their natural states or are artifacts of lab conditions. Replication of the environmental cues that may influence morphogenesis is made more difficult by extreme conditions that are hard to mimic (i.e., hydrostatic pressure), or that coexist with other extreme cues. Because marine fungi generally live in multi-kingdom polycultures, we presume that other organisms such as bacteria, viruses, algae, or other fungi influence morphology, in which case axenic culturing (where only a single species is cultured, making it free from other contaminating organisms) may not replicate native morphologies.

Challenges of identifying life cycles and morphologies of marine fungi are intertwined with other uncertainties regarding marine fungi distributions that require systematic sampling to capture cells that may be spatially and temporally sparse. Ideally, there would be systematic microscopy analysis of large-scale sampling endeavors, such as Traversing European Coastlines (TREC), that include fungal identification. Such an effort could use fungal specific dyes and AI-based image analysis approaches to identify potential fungal-shaped cells in image streams of plankton. Once morphology is coupled to species identification and culturing, life cycles could potentially be recapitulated in the lab to identify mating, sporulation, or growth forms in order to increase understanding of the functional state of fungi in different parts of the marine environment.

Question 10. How Can We Break Down Barriers to the Interdisciplinary Research Needed to Advance Marine Mycology?

In the two centuries since the first marine fungus was named, marine fungal researchers have described more than 2,000 species from the ocean (Jones et al., 2019), and the number of marine fungi publications have increased exponentially in the past decade. By exploiting this momentum, we can propel the field beyond observational science that forms the basis of early baseline research. Addressing the questions presented in this article can, and in many cases already has, enabled new paradigms about fungal roles in our oceans. So why does this list of questions remain?

Historically, mycologists tended to overlook the ocean as a potential habitat, focusing instead either on the ecology and diversity of macrofungi, like mushrooms, which are not found in the ocean, or on applied fields like plant pathology. Mycologists who were using culture-based techniques to study microfungi infrequently targeted marine sources (but see the extensive work of Jan Kohlmeyer, Erika Kohlmeyer, and Brigette Volkmann-Kohlmeyer as notable exceptions; e.g., Kohlmeyer and Kohlmeyer, 1971). Because it can take months or even years for incubation of marine substrates to yield macroscopic fruiting structures, much of the diversity of cultivable fungi may have been long overlooked or discarded in favor of other systems producing data more rapidly. Since the development of molecular methods, most microbial studies have focused on bacteria, including early large-scale, well-funded initiatives like the International Census of Marine Microbes (ICoMM), leaving fungal communities largely unexplored, and the methods and databases to study them underdeveloped. Critically, the lack of inclusion of fungi in these surveys has led to the widespread misconception that fungi do not contribute to ocean functions. Mycologists represent a small fraction of those studying microbes, and the proportion of mycologists focused on marine fungi are, by extension, even smaller.

Given these historical disadvantages, how can marine mycologists, as a field, proceed? One way forward might be to restore our prominence among, and integration within, the larger oceanic microbiome research community. Mycologists, or aspirational mycologists, should expand participation in research cruises (Figure 3), ocean science meetings, and international ocean working groups, and should contribute to large research analyses and funding initiatives. At the same time, marine fungal research should work toward building a positive public relations campaign to demonstrate the complexity and importance of these little-known organisms. Bacteriologists have effectively shifted perceptions of microbes as “germs” by advertising interesting and complicated symbioses (e.g., chemoautotrophy in hydrothermal vents, microbial probiotics that shield corals from bleaching, or the symbiosis of the bioluminescent marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri and the Hawaiian bobtail squid), and popularizing global species counts that are orders of magnitude higher than anyone would have imagined two decades ago. While fungi have captured some of the market share of popular science recently, these tend to emphasize terrestrial phenomena like mycorrhizal networks or entomopathogenic “zombie” fungi. In fact, there is no shortage of similarly charismatic fungal systems in marine habitats. Examples include the unusual patterns of cell division and polarity in marine yeasts (Mitchison-Field et al., 2019), fungal farming by salt marsh snails (Silliman and Newell, 2003), and “phycomycobioses” like the symbiosis between the brown alga Ascophyllum and the fungus Stigmidium ascophylli (Kohlmeyer and Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, 1998). These examples should be added to the next generation of oceanography and marine biology textbooks. Efforts to develop, execute, and disseminate appropriate monitoring and assessment methods for the conservation of aquatic fungi (Fernandes et al., 2024) or “counting” the number of fungal cells in the ocean are also underway (Breyer et al., 2025), serving the dual purposes of collecting data and raising awareness. A large and growing number of recent reviews of marine fungal biology provide an excellent overview of many of these efforts and offer an accessible entry point for those working to assess the state of the field (e.g., Richards et al., 2012; Amend et al., 2019; Gladfelter et al., 2019; Gonçalves et al., 2022; Calabon et al., 2023; Peng et al., 2024). Finally, including “tiny fungal earth” culturing modules in high school and undergraduate courses is another way to both expand sampling and recruit the next generation to the field. The fungal community must do a better job of publicizing these efforts to engender a sense of wonder surrounding the unknown fungal diversity within our ocean.

FIGURE 3. Recovery of a surface-tethered sediment trap at Station ALOHA on board R/V Kilo Moana. Ongoing research helps determine the role of fungi in nutrient cycling in the North Pacific Gyre. > High res figure

|

Meeting Conclusion and Next Steps

The remainder of the meeting concerned potential collaborations, grants, initiatives, and planning for the next occasional meeting. Meeting participants suggested that a meeting location outside of North America might help further diversify participation, and several potential funding agencies were suggested to partially defray costs. Readers interested in participating in, or hosting, the next meeting should contact the authors of this paper to be added to a running list of interested participants.

Acknowledgments

This paper was conceived and written during the second occasional meeting of marine mycology, Asilomar, California, a workshop funded by a generous grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. ASA acknowledges support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (award GBMF9343) and from NIH P20GM125508. OY acknowledges support from the Israel Science Foundation (grant number 888/19); TR from Centre for New Antibacterial Strategies (Tromsø Research foundation grant 2520855); NGC and CG from the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (Infrastructural Centre Mycosmo (MRIC UL, I0-0022), programmes P1-0198 and P4-0432); ASG from NSF (MCB2016022); HG from the MRC Centre for Medical Mycology at the University of Exeter (MR/P501955/2); and TYJ from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. KJEH was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (award #2141064). MAC and MDP acknowledge support from NIH/NIAID R01 grant AI50113-17, R01 grant AI39115-24 and R21 grant AI168672-02 awarded to Joseph Heitman, who is also Co-Director and Fellow of the CIFAR program Fungal Kingdom: Threats & Opportunities. CLE is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under an NSF Ocean Sciences Postdoctoral Fellowship (Award No. 2205744). MHG was partially funded by COPAS Coastal ANID FB210021. IG acknowledges the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, a DOE Office of Science User Facility that is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. XP acknowledges support from NSF (DEB-2303089) and the Simons Foundation (SFI-LS-ECIAMEE-00006491). CAQ acknowledges support from NSF (DEB2018215). AW was supported by NIH award 5T32AI052080-20. GZ is supported by NSF award DUE-1833880. This manuscript has been authored by an author at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The U.S. Government retains, and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges, that the U.S. Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, world-wide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes.