Full Text

Many university instructors receive end-of-semester responses to standardized student questionnaires (student evaluations of teaching, SETs) collected through online systems. But how well do SETs work to improve teaching and student engagement in learning? Research has found a large number of challenges and problems with SETs, including, (1) they do not assess teaching quality; (2) they often use quantitative, predefined scales that leave little space for additional comments; (3) they often have unclear goals, with course improvement not being the main one; and (4) there is often little student engagement, indicated by low response rates for online evaluation.

At the Geophysical Institute (GFI), University of Bergen (UiB), we consider high-quality feedback from students to instructors important in order to improve course outcomes. However, we wanted to move away from SETs and so looked for alternative feedback methods that would better represent student views (respecting both their qualitative and quantitative aspects) and could be presented to the instructors in a motivating way.

We chose to experiment with the Teaching Analysis Poll (TAP; Hawelka, 2019) that was, to our knowledge, developed at the University of Virginia and has been used in different higher-education institutions, countries (e.g., United States, Germany, Switzerland), and disciplines. The recommended TAP procedure for face-to-face classes takes about 30 minutes and is performed by an external facilitator who collects student feedback on three aspects, which are then communicated back to the class instructor:

- Which aspects of the course facilitate your learning?

- Which aspects of the course hinder your learning?

- What suggestions do you have for improving the obstructive aspects?

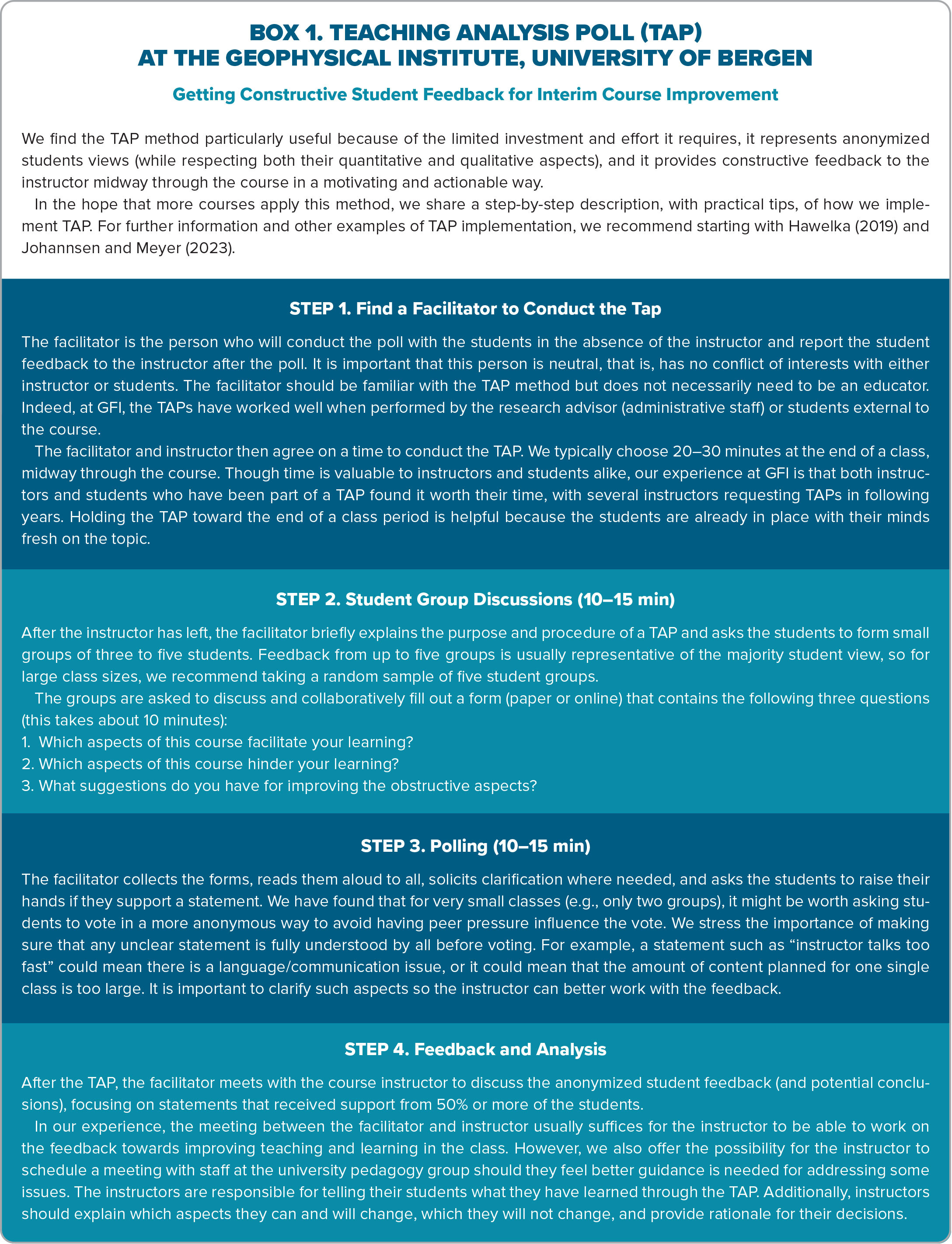

Box 1 provides a detailed description of the TAP procedure as employed by the authors.

|

The method can easily be adapted to different teaching situations. As facilitators, we have experience with TAP in both small courses with two or three student groups and very large courses with several hundred students; both face-to-face and online (using online collaborative writing and poll tools); and with both TAP on the course level and TAP on the study-program level (with students commenting on aspects related to the program curriculum). See the variants described in Johannsen and Meyer (2023).

At GFI, TAP implementation was part of a larger education initiative, iEarth Center for Integrated Earth Science Education, and of an ongoing collaboration with the UiB university pedagogy group. Between 2022 and 2024, we conducted seven TAPs in selected geoscience courses (many of which had a focus on active learning), and two courses repeated the TAP after one year. People involved were administrative staff at GFI, a university pedagogy colleague, and two students who served as TAP co-facilitators and helped analyze the data.

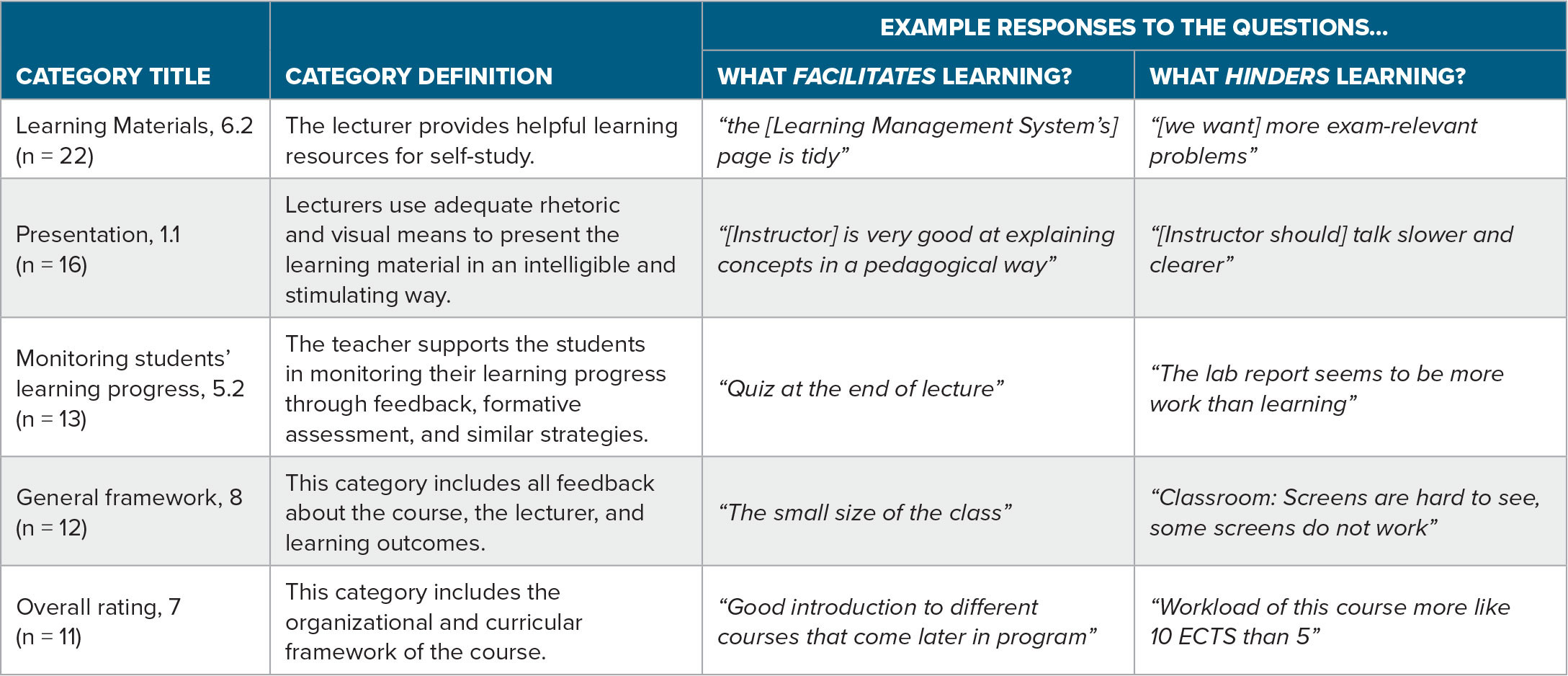

Because one of TAP’s characteristics is confidentiality, we will not detail TAP results. However, to provide an overview of the topics mentioned, we analyzed all TAP reports based on the categories identified by Hawelka (2019). Hawelka’s system includes eight main categories and several subcategories, ranging from comments about interactions between students and instructors to students’ understanding of the task, their motivation, their learning strategies, and their self-regulation for learning, to general resources and overall ratings about the course and about its structural conditions. Table 1 shows samples of the Hawelka (2019) categories that appeared most often in the TAPs together with examples of students’ positive or negative quotes.

TABLE 1. Relevant categories from Hawelka (2019) identified in GFI TAP, 2022–2024. The first and second columns indicate the category titles, number of responses (n), and definitions. The third and fourth columns show example GFI TAP responses in each category. > High res table |

TAP results provide not only general positive or negative views (Category No. 7) but also comments on more specific points, such as the learning materials (Category 6.2) or the lecturer’s presentation style (Category 1.1). In fact, most comments found in the TAP were about aspects that the instructors typically can change. Rather surprising to us, the students commented on aspects that support their learning progress (Category 5.2), specifying positive and critical examples. This indicates that the TAP stimulates the students to evaluate what others, such as the instructors, do, as well as what they need for their own learning success. This is a huge advantage of the TAP compared to traditional SET methods. Finally, some TAP feedback relates to aspects that instructors alone typically cannot change (Category 8).

We believe that instructors should respond to a TAP session by telling their students what they learned from it. Additionally, they should explain to students which aspects they can and will change, as well as those they will not, providing the rationale for their decisions. In our specific case, forwarding some of the student feedback to the study administration led to some structural improvements, such as better equipment in classrooms. The feedback we received from the instructors was all positive—important, considering that they had to invest 30 minutes of their valuable class time to administering the TAP.

If you are interested in trying out TAP as a feedback method, we recommend aligning your evaluation approach with the instructors’ and study programs’ needs and goals. The TAP could be part of a larger transformation process that could also, for instance, include introducing active learning or alternative teaching methods. To gain experience with TAP, it is useful to employ two facilitators, to start small with a few courses, and then to build a team of people who can facilitate TAPs. Because staff time is often limited, TAP facilitators could include students, which is something we have done and have found to work well. We know of at least one university (University of Erlangen-Nuremberg) that trains students to be TAP facilitators. Working together with students in this way is a great example of student-staff partnership and co-creation. Feel free to contact us to discuss TAP (https://cocreatinggfi.w.uib.no/contact/).

> High res box

> High res box