Introduction

Employee Resource Groups (ERGs), sometimes referred to as affinity groups, have existed in the US workforce for decades and are widely used in private industry (DiversityInc, 2020). These voluntary, employee-led groups are gaining popularity in the US federal workforce and are typically composed of employees with shared identities such as race, gender, or sexual orientation, or individuals who are drawn together by a shared interest, experience, or allyship goal (DiversityInc, 2020). ERGs advocate for employees and foster spaces where employees can be their authentic selves, providing important micro communities of safety in the workplace. ERGs usually have defined structures with leadership roles and clear goals, and some have budgets to execute ideas and work with leadership to enhance DEIAJ goals.

The first ERG was formed in the 1960s when African-American workers at Xerox organized to discuss racial tension in the workplace. Since then, ERGs have become increasingly relevant. Many US federal government agencies have committed to creating more diverse, inclusive, and equitable workplaces as mandated by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Furthermore, Presidential Executive Orders issued by the Biden Administration have mandated federal agencies to advance DEIAJ efforts (E.O. 13985, 2021; E.O. 14035, 2021).

NOAA plays a critical role in shaping international ocean, fisheries, weather, and climate communities, and as a federal agency, is in a unique position to amplify DEIAJ in the ocean sciences. The agency is working to harness the lived experiences and perspectives of underrepresented and marginalized groups that are actively involved in DEIAJ efforts through more than 10 ERGs that are primarily organized around traditional affinities (e.g., race, ethnicity, individuals with disabilities, sexual orientation, and gender identity; see Ali et al., 2021). We acknowledge there is no single approach to addressing every marginalized identity, but ERGs provide a space to share experiences, build community, and develop skills of persistence, resilience, leadership, and success. Several NOAA ERGs were recently awarded the Diversity Impact Award by the Global ERG Summit organized by the University of Southern California Marshall Center for Effective Organizations. These included one of NOAA’s first ERGs, the Diversity and Professional Advancement Working Group (DPAWG). This article outlines the benefits and tangible practices of ERGs that can be used to build DEIAJ in ocean sciences.

Unlike many DEIAJ articles that assume a “top-down” approach where actions come directly from leadership, devoid of voices from marginalized groups who are directly impacted, this article provides a “bottom-up” approach to achieving an anti-racist strategy from the people who are impacted and purposefully engaged in creating micro communities of safety through ERGs. This “bottom-up” approach refers to the honor, regard, and privilege that we place on our lived experiences as Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC), and the centering of this knowledge helps guide and shape both leadership within an organization and participation in the ERG space. The three authors are active members who have leadership roles within the DPAWG, find that these tangible ERG practices offer ways of knowing, through lived experiences, certifications in DEIAJ, and common actions that can be taken to protect members of marginalized groups. The lead author no longer serves at NOAA but is now an assistant professor at Hampton University.

Here, we seek to redefine the expertise, and we reject that it is limited to special skill or knowledge characterized by the methods and principles of traditional science. We instead embrace all ways of knowing, including the understanding, ability, and unique perspectives of marginalized groups that are developed through their lived experiences.

The Diversity and Professional Advancement Working Group as an ERG Model

The Diversity and Professional Advancement Working Group (DPAWG) was created in 2014 as NOAA’s first ERG to further extend opportunities to STEM students from underrepresented groups who participated in NOAA educational programs. The DPAWG has since evolved to encompass a dynamic group of professionals from across NOAA who recognize the value of teamwork and the importance of diversity and inclusion in the workplace. DPAWG members have a passion for diversity and inclusion, elevate issues of concern to the proper forums, and serve as a unified voice to advocate for change through DEIAJ practices.

DPAWG leadership structure includes two co-chairs, an executive secretariat, and six co-leads of three subcommittees who together comprise the executive committee. The co-chairs and co-leads are chosen through a nomination and election process and serve three- and two-year terms, respectively. The executive secretariat is appointed by the co-chairs. Along with members, the leadership team establishes DEIAJ priorities based on group feedback to ensure inclusivity and that priorities can be accomplished with the current capacity of the group. Because an ERG is a voluntary employee group, members do not formally measure and evaluate retention, diversity, and other aspects, as those measurements are human resources functions. Instead, the DPAWG takes honest feedback from members in order to evaluate and prioritize goals, and it finds consensus through voting. The group also has an executive sponsor, a member of NOAA’s Senior Executive Service (SES) who provides strategic counsel to the executive committee. In addition, the group shares priorities with the SES to establish leadership buy-in. A monthly general body meeting includes updates from co-chairs and subcommittee leads on activities. Trainings that are also a part of the monthly meetings include such topics as resume writing, salary negotiation, mental health check-ins, how to identify and respond to sexual harassment and assault, and other DEIAJ-related topics.

The DPAWG started with 14 members, many of whom were former participants in NOAA’s Educational Partnership Program with Minority Serving Institutions. Membership has now grown to more than 60 who represent staff at all levels and disciplines across the organization, as well as all genders, races, and ages. A decade after its initiation, DPAWG continues to advocate for attracting, retaining, supporting, and advancing a diverse NOAA workforce. Serving as a safe haven, DPAWG provides a network for individual members who feel marginalized and isolated while also supporting the efforts of the agency, through regular meetings with leadership, to become more diverse and inclusive. Since its founding, DPAWG has received organizational and national recognition as a change agent for its DEIAJ efforts. After the death of George Floyd, the group authored an open letter to NOAA leadership that included a list of recommendations for creating and expanding leadership development programs, including the agency’s premier leadership program. Many of these recommendations were adopted by the agency, including eliminating the barrier of supervisor approval during the initial application process, diversifying the reviewer panel, and expanding the pool of those who can apply. DPAWG was nationally recognized for this advocacy. Other efforts include the development of a diverse hiring platform, tOol foR Diverse IntERview PanelS (ORDERS), that provides hiring managers with a list of ~120 people with diverse backgrounds who are available to serve as panelists and contribute to the hiring process. In addition to these organizational accomplishments, the DPAWG network has nurtured many of its founding members into NOAA leadership positions.

ERG Benefits and Tangible Practices

ERGs create a sense of belonging and place of safety for underrepresented and marginalized groups.

Dutt (2020) reports that most BIPOC in the geosciences view race as an essential part of their identity, and references to race and racism often make them feel seen and heard. Although race is at the core of many peoples’ identities, individuals from BIPOC communities often fear the discussion of race in predominantly White settings because of tensions that may impact advancement, job security, and safety, especially in hierarchical settings such as government.

Because they are formed naturally based on marginalized identities and common experiences, ERGs provide safe places to discuss race, ethnicity, and other affinities that may be core to identity. They provide welcoming spaces for those who experience oppression to discuss solutions to such issues in the workplace. These micro communities of safety enable transparency, honesty, and opportunities to openly share successes and failures without the burden of conforming to the culture of predominant settings. In these spaces, ERG members are encouraged and supported to be their authentic selves and discuss experiences without the need to conform or assimilate to a restricted definition of professionalism.

Research suggests that factors contributing to a sense of belonging for those in science include interpersonal relationships, personal interest, and science identity (Rainey et al., 2018). At NOAA, ERGs meet regularly to share personal and professional experiences and lessons learned and to provide advice on subjects ranging from resume building to how to give effective presentations, share resources, and nominate each other for awards. This allows ERG members to feel seen and heard and provides opportunities for them to develop strong interpersonal skills. ERG spaces allow members to freely cultivate their identities and empower members to resist hegemonic narratives by taking control of their own narratives.

ERGs provide informal mentorship that is essential for career advancement.

To establish a culture of diversity in the workplace, opportunities for continued engagement among employees are necessary (Asare, 2019). Navigating majority spaces as a marginalized minority can be intimidating, and underrepresented groups are often lost in engagement opportunities. Mentoring offers active employee engagement and provides a natural learning environment for personal and professional growth. Those who have positive mentoring experiences are more likely to be promoted, earn more money, have clear career plans and goals, and serve as mentors themselves (Heidrick & Struggles, 2017; Rockinson-Szapkiw et al., 2021). Due to affinity bias—the tendency to favor people who share similar interests, backgrounds, and experiences—most formal mentoring programs select individuals who share similar likeness, backgrounds, and experiences as the dominant workplace culture, while often rejecting those who act or look differently. This leaves traditionally underserved groups lacking in mentorship. ERGs provide informal mentorship that builds confidence in the workplace as members offer guidance and advice, help newcomers acclimate to culture and introduce them to colleagues, share job and other opportunities, and provide space to discuss and work through problems. Furthermore, ERGs can offer the safety and opportunity to develop cross-cultural competencies as they often are composed of people with multiple marginalized identities (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, age), which further helps navigate difficult spaces. Research shows that women and marginalized and minoritized groups indicate mentoring as important aspects of their careers (Asare, 2019), and that women of color who have mentors of color and/or women mentors report higher job satisfaction and are more likely to stay in the workplace. Therefore, mentorship for marginalized groups not only leads to workplace advancement but also enhances retention. For these groups, mentorship helps them adapt to new environments faster and offers a sense of connection to a larger community where they might otherwise feel lost (Thomas, 2012). In addition, Kemlo (2010) found that when more advanced students mentor first-year students, the latter are likely to display motivation and desire to achieve career goals.

ERGs generate access to professional development opportunities.

Employees who pursue professional development opportunities have higher productivity and job satisfaction (Meyer, 2023), yet not all employees have access to them. Historically in ocean science, access has been limited to mostly able-bodied, White, cisgendered, heterosexual men (Ali et al., 2021). According to a study conducted by the Institute for Corporate Productivity (2018), business professionals at high-performing organizations view ERG participation to be more effective than formal development programs in terms of maturing a variety of leadership skills that may not be readily available in their day-to-day roles. These roles could include budget oversight and execution, strategic planning and implementation of ideas, creating impactful communication media and documents, overseeing teams and working groups, and public speaking.

Likewise, because ERGs often interact with other ERGs and diversity initiatives across an organization, they afford members access to a wide audience to drive change. ERG leaders are subject-matter experts for their respective groups and can be utilized by senior leadership for feedback about working with people within their diverse communities. This presents opportunities to demonstrate skills in organizational leadership and to foster higher visibility within an organization.

ERGs also develop their own internal ongoing opportunities for improving skills and knowledge through professional development. For example, ERG members review resumes and provide helpful feedback, conduct mock interviews, and give insight to the exact experiences and skills needed for positions. All these skills are critical for advancing careers and contributing more to the workplace, as well as boosting morale, productivity, and satisfaction (Meyer, 2023).

ERGs benefit and drive change in the workplace culture of an organization.

Ocean science is one of the least diverse sciences (Bernard and Cooperdock, 2018). While many understand and acknowledge the racial disparity in ocean science generally, it’s difficult to tease out such disparities in the workplace. ERGs consistently discuss and actively find solutions to the lack of DEIAJ that not only create safe spaces for members but also help drive changes in workplace culture. The presence or lack of interpersonal relationships is one of the most common reasons cited for feelings of belonging or lack of belonging in STEM (Rainey et al., 2018). For federal agencies focused on increasing and retaining employees from traditionally underrepresented groups, ERGs serve as safe spaces for forming positive connections, they encourage interpersonal relationships, and they are likely to be productive strategies for attracting and retaining diversity in the organization. In addition, the informal mentorship and professional development opportunities created in these groups lead to employee satisfaction and retention without the financial cost of external development or training activities/programs.

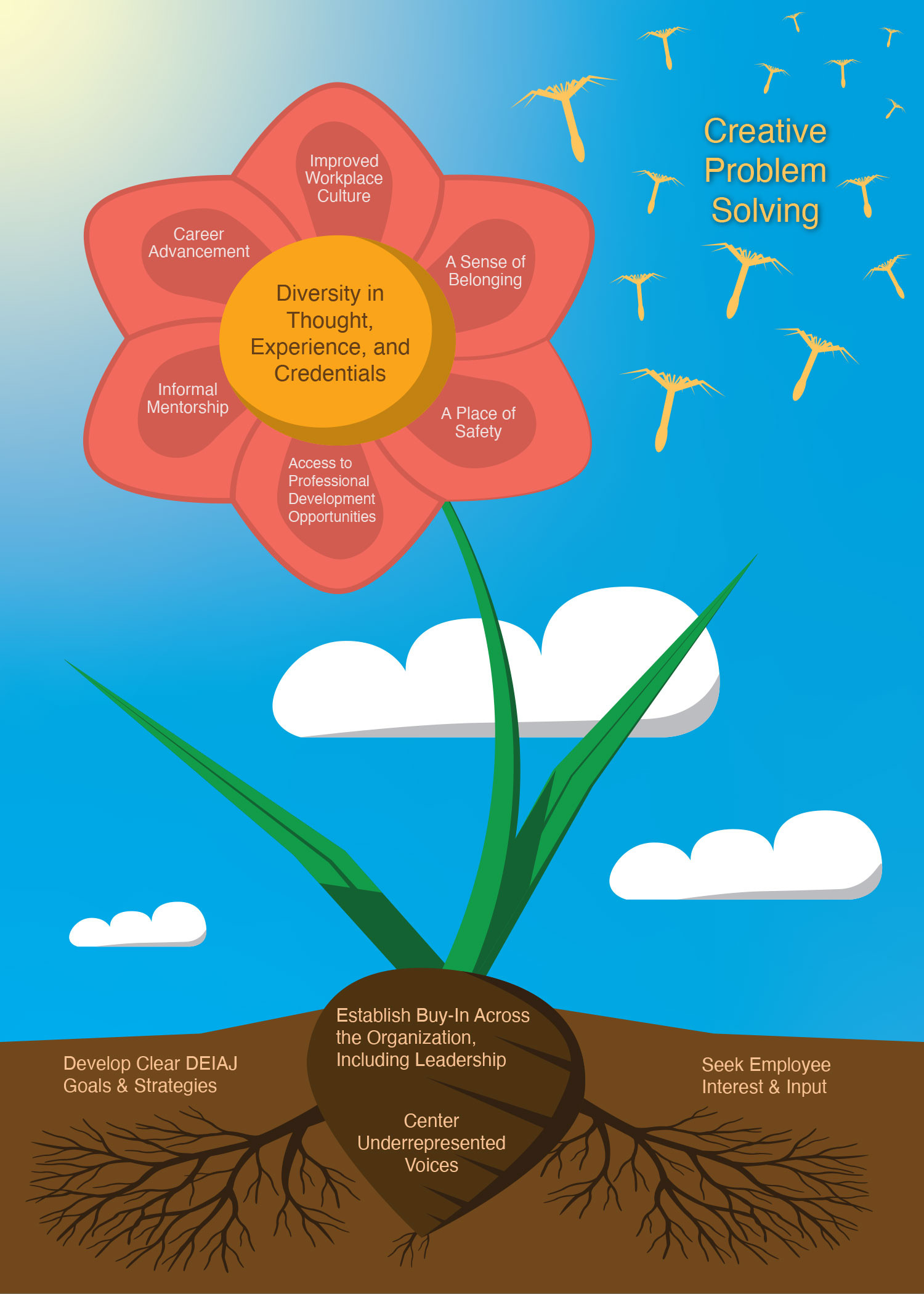

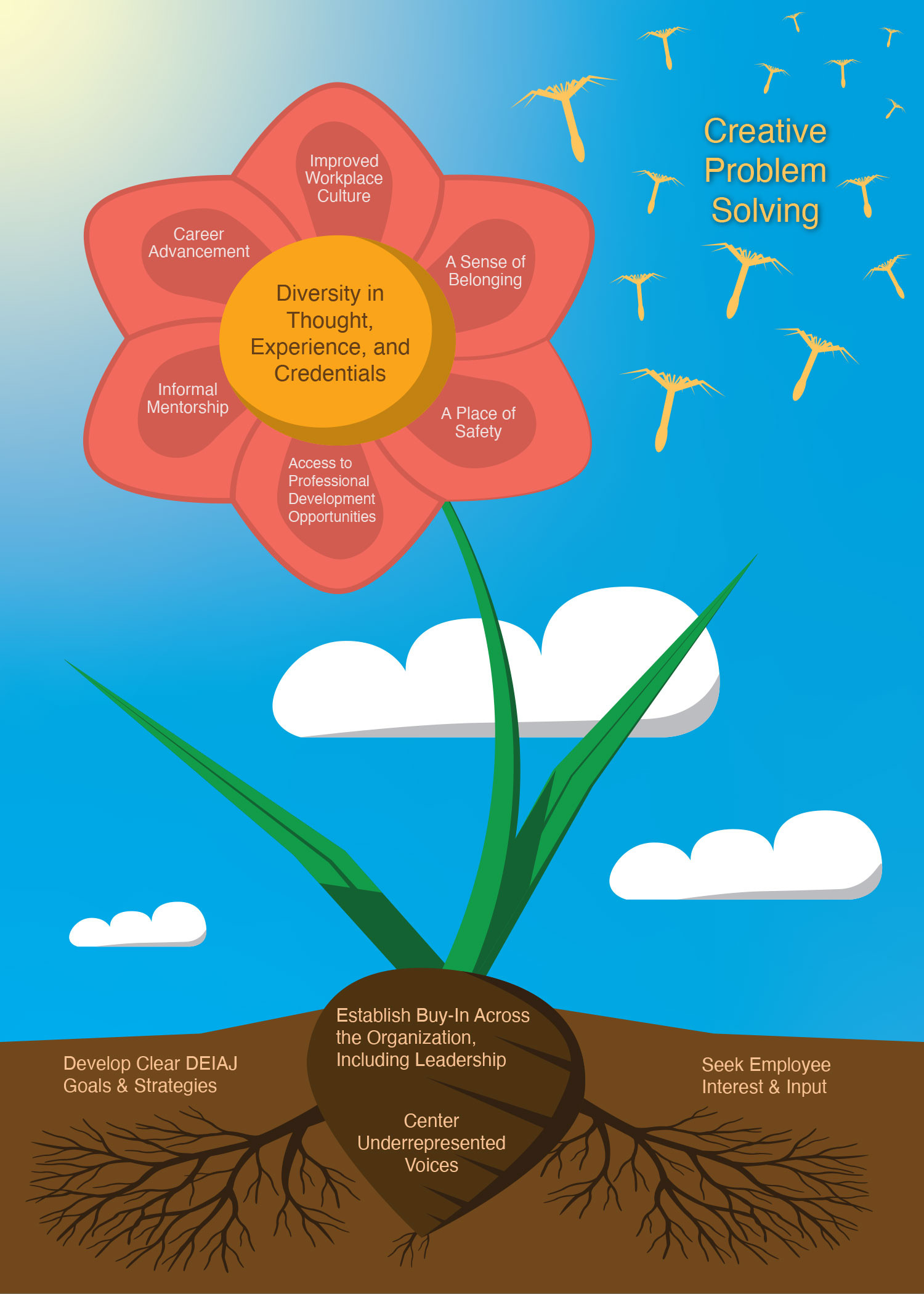

ERGs can also provide benefits to organizations in critical mission areas as society faces complex and pressing ocean-related issues. For example, ERGs can provide access to the perspectives and lived experiences of diverse constituencies needed to address global crises such as climate change. Diversity in thought, experience, and credentials produces the best results and the most creative problem solving. In addition, it is important for agencies to have representation of the population and stakeholders that they serve.

Lessons Learned

While there is no “one-size fits all” for starting an ERG, one key lesson learned for initiation is seeking employee interest and input to foster inclusivity. Second, developing clear DEIAJ goals and strategies based on input from the group creates a sense of ownership and belonging in the ERG and empowers members to play active roles in creating solutions towards DEIAJ goals. A third important lesson learned concerns the need to garner buy-in from outside ERG membership, including from higher-level executives and leadership. Having senior-level executives champion ERG goals and ideas allows for broader reach and impact and fosters collaboration as opposed to contention due to differences in workplace identities, values, and beliefs. Aligning some of an ERG’s DEIAJ goals with overall workplace goals can enhance these relationships.

Conclusions

Research has shown that ERGs provide a great deal of agency value, from individual members of the workforce to top leadership, and even across corporate culture (Jennifer Brown Consulting, 2010). Some of the more tangible benefits we have discussed here (Figure 1) are that ERGs help to promote an equitable, inclusive, and respectful workplace; improve cross-cultural and multicultural awareness; and support employee engagement and networking opportunities. Moreover, there are intangible benefits such as offering a sense of community and belonging that might not exist for certain groups otherwise; helping to create safe spaces to speak truths without fear of retribution; sharing of “unwritten rules” that can be elusive but important; providing a collective voice around shared interests and goals; and helping to expand employees’ perceptions of where they belong, who they can become, and how they show up, which all play an essential role for diversity in the ocean sciences.

FIGURE 1. Lessons learned from Employee Resource Groups (roots) and benefits and tangible practices of NOAA’s Diversity and Professional Advancement Working Group (DPAWG) that can help shape diversity, equity, inclusion, accessibility, and justice (DEIAJ) in workplaces (petals). These collectively help create more DEIAJ needed in the field of ocean science. Illustration by Thia Griffin-Elliot. > High res figure

|

The skills cultivated through participating in ERGs can also help to develop and support future leaders through opportunities for career advancement, education, and professional development; provide access to mentors, champions, leaders, and other role models; and help employees gain deeper insight into agency structure, function, and culture. If properly tapped, the enhanced business value of ERGs can include providing critical insight into diverse communities, increased credibility and contacts with external diverse constituencies, enhanced employee loyalty and commitment, and increased retention and performance of diverse groups. ERGs can also be effective early warning systems to raise concerns before they result in major issues, and expanding membership of ERGs throughout an agency allows for embedded change agents across agency functions. Finally, a diverse workforce in ocean science yields diverse perspectives and skills that are needed to solve global ocean problems. Creating inclusive and diverse spaces in ocean science leads to increased belonging, innovation, and success on all fronts.

Acknowledgment

We thank Thia Griffin-Elliott for creating the figure.