Background

Sexual harassment in ocean science is pervasive. According to a recent report by Women in Ocean Science (2021), 78% of surveyed females have experienced sexual harassment in their workplaces or learning environments, with fieldwork representing the most common location for such experiences. While individual perceptions (regardless of legal definitions) of what constitutes harassment and bullying might vary, with some defending behavior as, for example, universally difficult personalities or cultural overcorrection (e.g., Harris, 2022), for the purposes of this discussion, sexual harassment includes gender-based harassment (e.g., threats, slurs, lewd comments and images, promoting stereotypes, demonstrating bias and discrimination, or other hateful conduct), unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. It is not limited to those who identify as women; it can also be aimed at perceived sexual orientation and gender identity.

Fieldwork can be a training ground for students, a requirement for earning a degree in geoscience, and a deciding factor in recruiting and retaining individuals to the field. Shafer et al. (2022) analyzed geoscience job postings and found that over 60% of Earth science job postings aimed at bachelor’s-level graduates listed “field skills” as a desired qualification and was the second-most prevalent qualification of the 34 skills the study examined across over 1,000 unique job postings. It follows that broad access to and positive experiences in fieldwork can lead to increased recruitment and retention in the field (Nelson et al., 2017; NASEM, 2018; Marín-Spiotta et al., 2020).

Environments that promote, normalize, or deal ineffectively with sexual and other forms of harassment are unsafe for researchers and staff, and can negatively impact both the mental and the physical health of people who experience harassment, as well as those of bystanders (Armstrong et al., 2018; Marín-Spiotta et al., 2020). Physical distance from an individual’s home institution while conducting fieldwork, paired with the power imbalances inherent to the hierarchical nature of academia and STEM leadership that is historically dominated by white men, can create or amplify a hostile or dangerous climate for people with marginalized genders or other marginalized identities (Marín-Spiotta et al., 2020; Kelly and Yarincik, 2022). People whose identities intersect multiple marginalized groups are at higher risk for harassment (NASEM, 2018) and can experience both racial and sexual harassment simultaneously or experience racially motivated sexual harassment (Armstrong et al., 2018). Given the lack of diversity in geosciences in the United States (e.g., Bernard and Cooperdock, 2018), ensuring that people at all career stages are protected from racial-, ethnic-, gender-, or ability-based harassment is crucial to creating a more diverse and equitable field—and it’s simply the right thing to do. Everyone deserves to be treated with respect in their workplace or learning environment, and a climate of respect has been found to lead to reductions in identity-based harassment (Robotham and Cortina, 2021).

Due to the many factors that can contribute to an “unsafe” field site, which range from personal- to institutional-level concerns, there is no single solution to making field sites safer from sexual harassment. Instead, ensuring field safety requires multiple policies and best practices that cover a wide range of topics, timescales, and levels of responsibility. Broadly speaking, there are three dimensions of safety that need to be addressed at field sites: harassment prevention, support for those who experience harassment, and response to incidents.

Current policies and social norms at many institutions are insufficient for ensuring inclusive and harassment-free environments (NASEM, 2018). In the field, participant safety also suffers from this isolating culture and a lack of clear and enforced policies, compounded by an environment with multi-institutional—and sometimes multinational—teams and field sites under various jurisdictions, and this complexity can complicate the question of responsibility when it comes to addressing instances of harassment or assault (Kelly and Yarincik, 2022). To remedy this situation, institutions and vessel operators must create and routinely update policies for harassment prevention, support, and response. Critically, once such policies exist, to be effective, institutions must communicate the policies consistently to all working at a field site and enforce them. In addition, those in positions of authority must be familiar with the policies so that they are equipped to assist targets of harassment—assuming they are reported (Clancy et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2017; Steinhardt, 2018). Unfortunately, of the individuals who have reported their harassment or assault, few say they have been satisfied with the outcomes of reporting (Clancy et al., 2014), and this situation has likely led to underreporting of harassment incidents.

Bystander training in intervention and reporting should be a regular part of field instruction (Kelly and Yarincik, 2022). While ensuring the safety and culture of a field expedition often falls on those in charge, such as chief scientists and principal investigators (PIs), all participants have a role to play in creating a positive culture and demonstrating lack of tolerance for poor behavior.

Developing a Safety Checklist

The Workshop to Promote Field Safety in Ocean Sciences, convened by the Consortium for Ocean Leadership and held May 17–18, 2022, in Washington, DC, was a follow-on event to the 2021 Workshop to Promote Safety in Field Sciences, which aimed to build a safer and more inclusive field culture for participants of all backgrounds and identities. The 18 participants assembled a set of broad recommendations to inspire and guide different audiences and actors in field science to address harassment in a collaborative, community-based manner. The ocean-focused workshop used the Report of the Workshop to Promote Safety in Field Sciences (Kelly and Yarincik, 2022) as a foundational document to guide the development of recommended actions specific to the ocean science community and ocean science field platforms. Participants represented a variety of career stages and sectors of expertise, including but not limited to academic and federal seagoing scientists, UNOLS members, private research vessel operators, and others interested in promoting safety and inclusion, in order to reflect a broad range of experiences and to reduce bias when crafting recommendations. The workshop operated on the premise that, in addition to being research misconduct, harassment and assault are health and safety hazards and, accordingly, should be taken as seriously as other health and safety hazards on research vessels and other field stations or platforms.

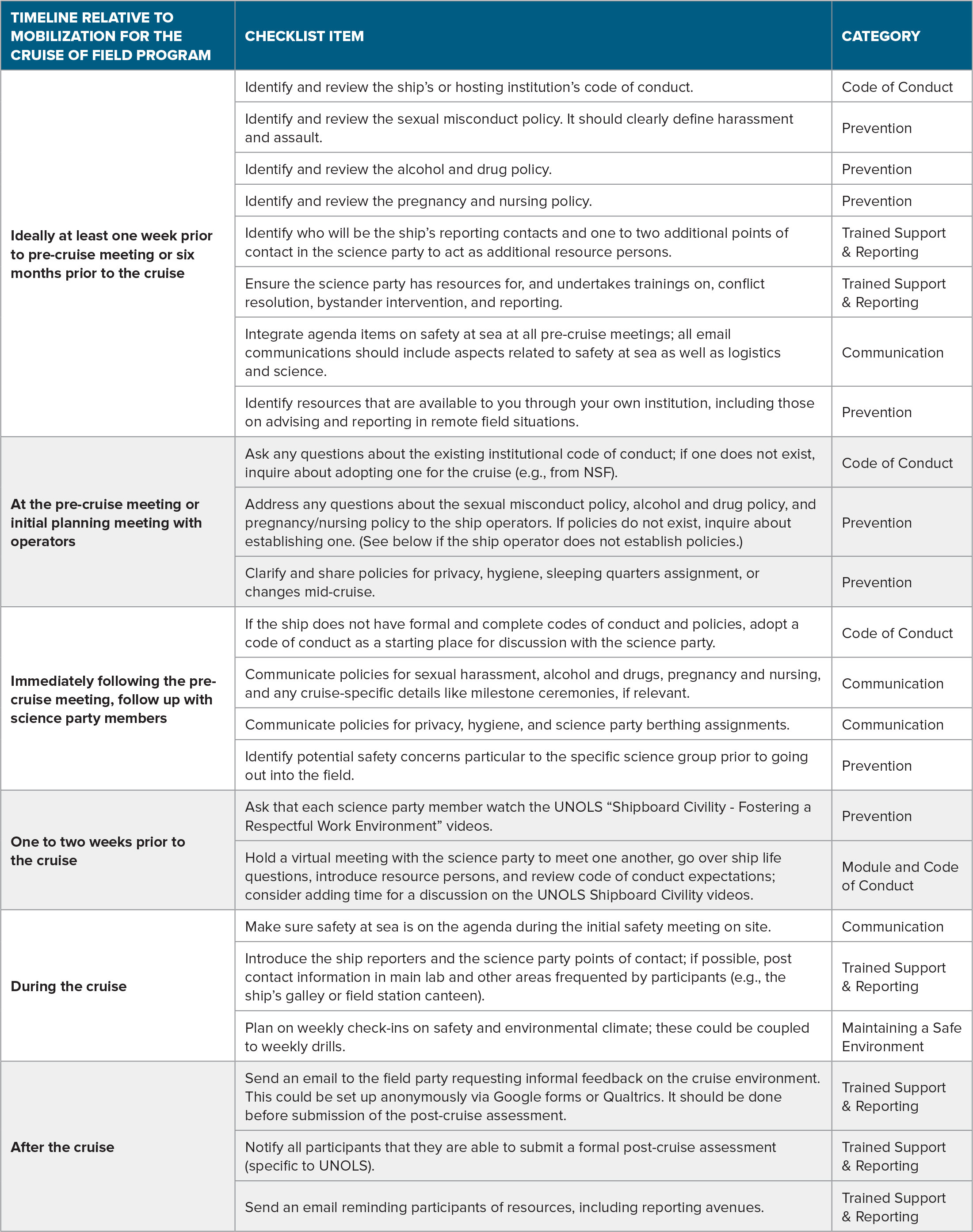

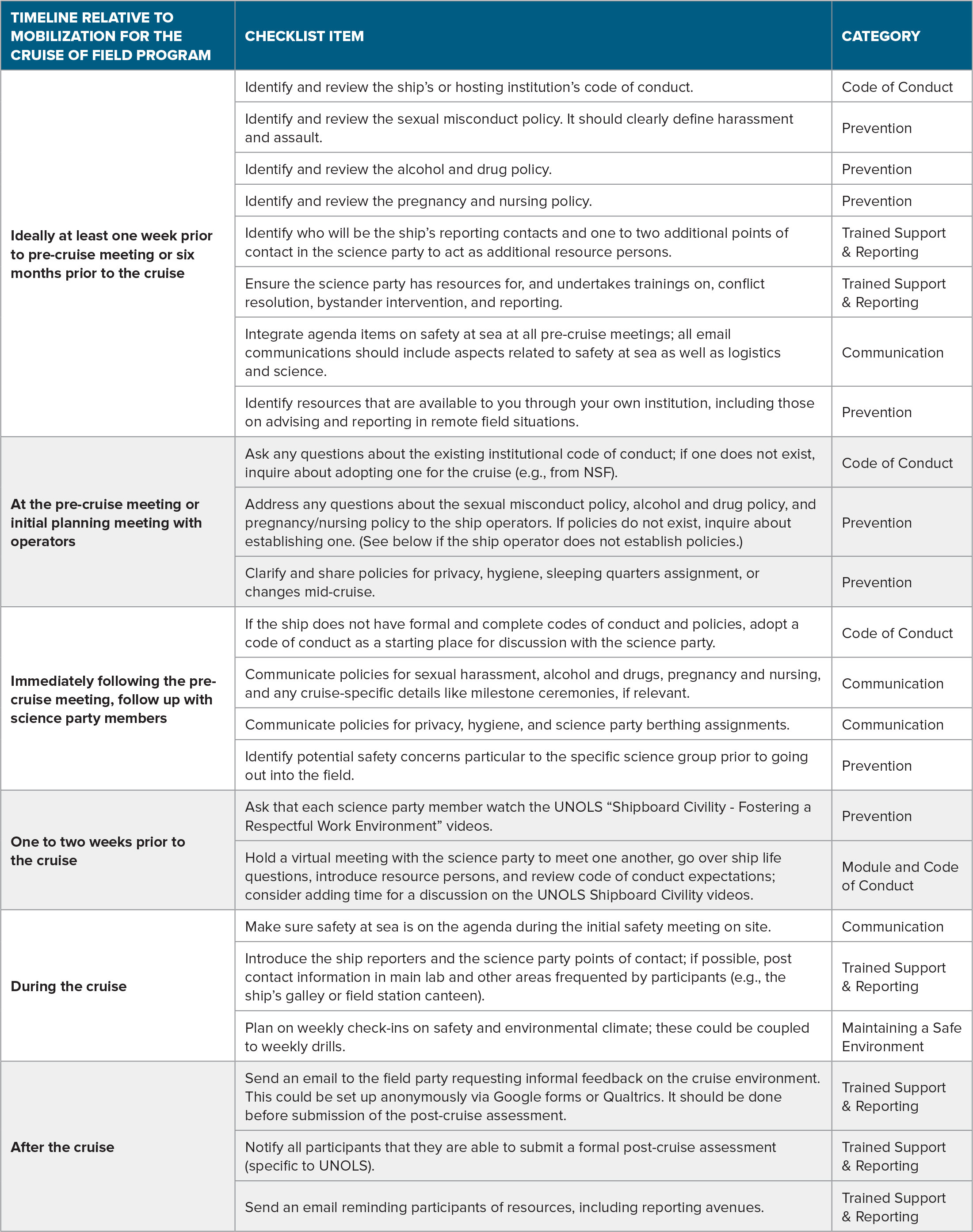

Workshop participants developed a vessel safety checklist to provide specific and realistic steps that managers, policymakers, and field team leaders in the ocean sciences community can implement immediately to improve policies and processes related to safety and to positively impact the culture of ocean science. By following the structure and timeline often used for scientific and logistical planning, the checklist aims to integrate safety into pre-, syn-, and post-cruise activities by outlining how and when to implement practices for preventing harassment, supporting targets of harassment, and encouraging reporting of incidents. The framework is intended to be flexible enough to allow institutions or individuals to amend the list as necessary for their unique purposes or as they learn new best practices. Implementation of the checklist should be treated as an iterative process that evolves with feedback and experience to better serve the community’s goals.

The Safety Checklist: Responsibility, Conduct, and Policies

While safety at sea requires that everyone bear some responsibility for keeping themselves and their colleagues safe, in developing this checklist (Table 1), workshop participants specifically envisioned it as a resource for PIs, chief scientists, and organizations. Though it is not exhaustive, it should help them prepare strategies for keeping all field participants safe from harassment and bullying. Planning should begin as early as proposal development. The National Science Foundation, in particular its Directorate for Geosciences, recently announced that several solicitations will require submission of a plan for safe and inclusive work environments, pointing to the importance that funding agencies are beginning to put on harassment as a safety issue (see NSF, 2023, Chapter II Section E.9).

TABLE 1. Checklist to promote field safety for chief scientists, principal investigators, and field team leads. The checklist is organized by three categories: When the action needs to occur, what the action is, and what dimension of preventing or responding to harassment it addresses. > High res table

|

The items in Table 1 serve to ensure that critical communications and policies related to safety planning are not overlooked, including the creation of individual codes of conduct that represent the shared values of the field team and organizations involved in each expedition; identifying mandatory reporters and additional trained resource providers (Kelly and Yarincik, 2022); clarifying multi-institutional roles and responsibilities that can confuse reporting of and response to sexual harassment (Kelly and Yarincik, 2022); and thinking through traditions that may not feel inclusive to those new to seagoing research, such as milestone ceremonies (UNOLS MERAS Committee, 2019). One common theme throughout the checklist is clear, consistent, two-way communication among the science team members who will be on board.

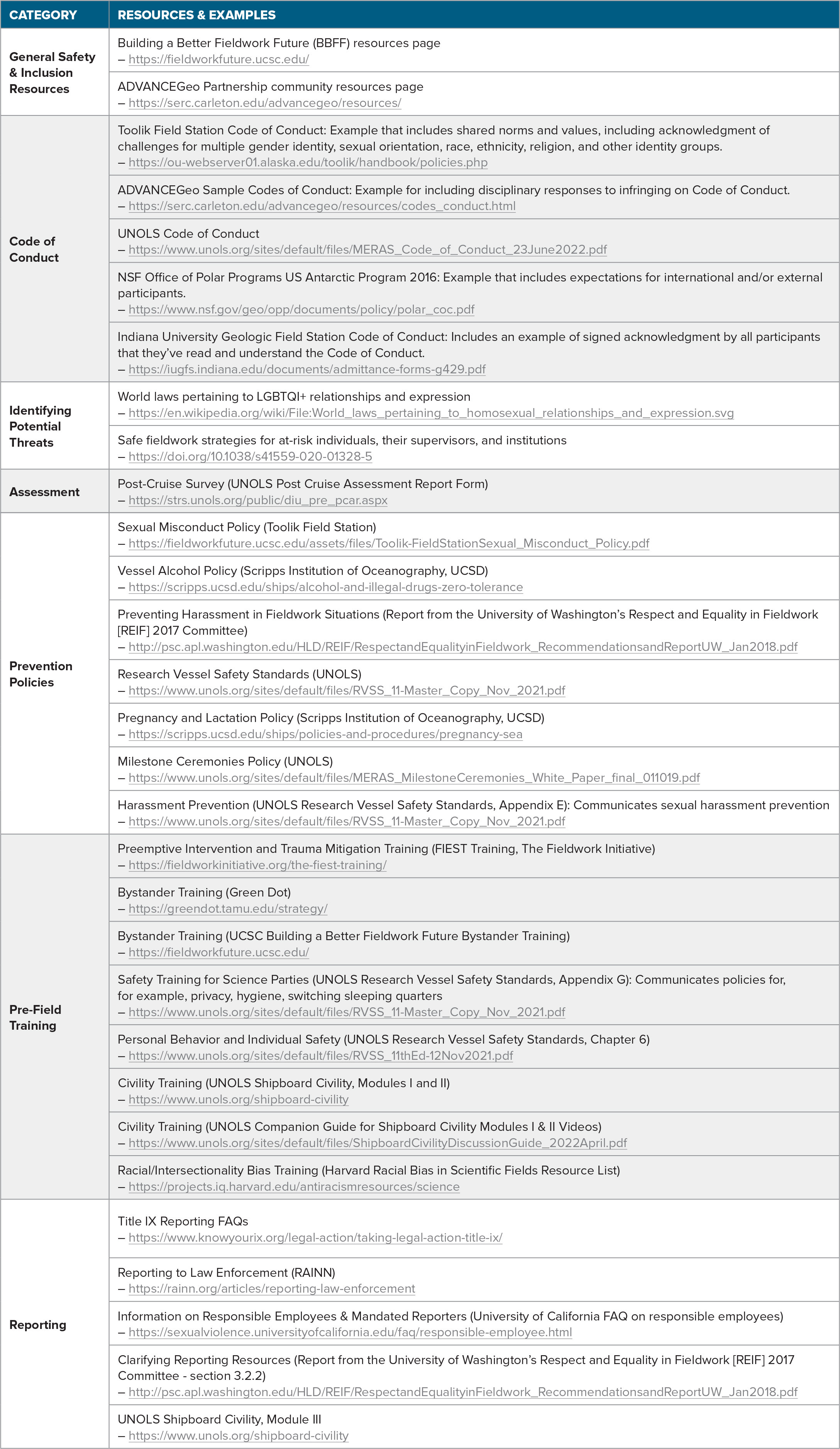

The left column of the safety checklist (Table 1) lays out when actions need to be taken relative to the research expedition. Not all expeditions will have the same planning timelines. The PI or chief scientist should be responsible for managing the safety checklist and ensuring that each action is executed, and at the appropriate time. Table 2 directs the PI or chief scientist to resources available to support the recommended safety planning and preparation actions in the checklist.

Conclusion

As is true for almost every other aspect of working in the field, preparation is the key to success. Having a plan in place to prevent sexual harassment, support targets, and respond to incidents on a ship is key both to the short-term goal of safely and positively completing field research and to the long-term goal of preventing attrition of talented scientists. It is important for teams going into the field to implement policies, trainings, and other measures that make participants safer from sexual harassment.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant OCE-1938766. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation, NASA, or the Department of Defense or its components. We thank two reviewers whose comments improved this manuscript.