Introduction

A hovercraft is a surface effect vehicle1 that requires a relatively level surface, so it has mostly been used across sheltered open or frozen waterways and mudflats. Its potential for support of polar travel was advocated 60 years ago (Fuchs, 1964, 1966; Law, 1965), but serious field tests have only been sporadic in the High Arctic (Abele, 1966; Cooper and Storr, 1967; Fowler, 1976; Kordenbrock and Harry, 1976) as well as in Antarctica (Caffin, 1977; Cook, 1989; Dibbern, 1989; Murao et al., 1994; James’ Hovercraft Site). The most continuous polar use of a hovercraft has probably been petroleum industry operations initiated in 2003 between Prudhoe Bay and the offshore North Star Production facility (Dickins et al., 2008).

Our use of a hovercraft as a science platform over sea ice in the Arctic Ocean is outlined in Hall and Kristoffersen (2009) and documented in Kristoffersen and Hall (2014). Much of the past criticism of the use of air cushion travel over sea ice stems from an obsession with speed; a substantial hover height is needed to be able to traverse several-meters-high ice ridges at high speed (Hibler and Ackley, 1974; Tucker and Taylor, 1989). These challenges to operating over Arctic sea ice are in stark contrast to the vast areas of smooth, hard blown snow on the Antarctic ice shelves, which present optimum conditions for hovercraft travel (Cook, 1989).

All the operational experience discussed here refers to the Griffon TD2000 hovercraft, which has a practical hover height of about 0.5 m when loaded (0.7 m unloaded). It has 25 m2 of usable deck area, and the 2.2 tons payload capacity can be divided between fuel, personnel, and scientific gear, depending on mission objectives (Figures 1 and 2). The craft’s relatively narrow, 2.2 m hull can navigate narrow passages between ice blocks and cross saddle points on pressure ridges. We adapted a range of scientific equipment items for use on the hovercraft or fabricated new versions to achieve reduced weight (Kristoffersen and Hall, 2014). The craft was given the name Sabvabaa, which means “flows swiftly over it” in the Inuit language.

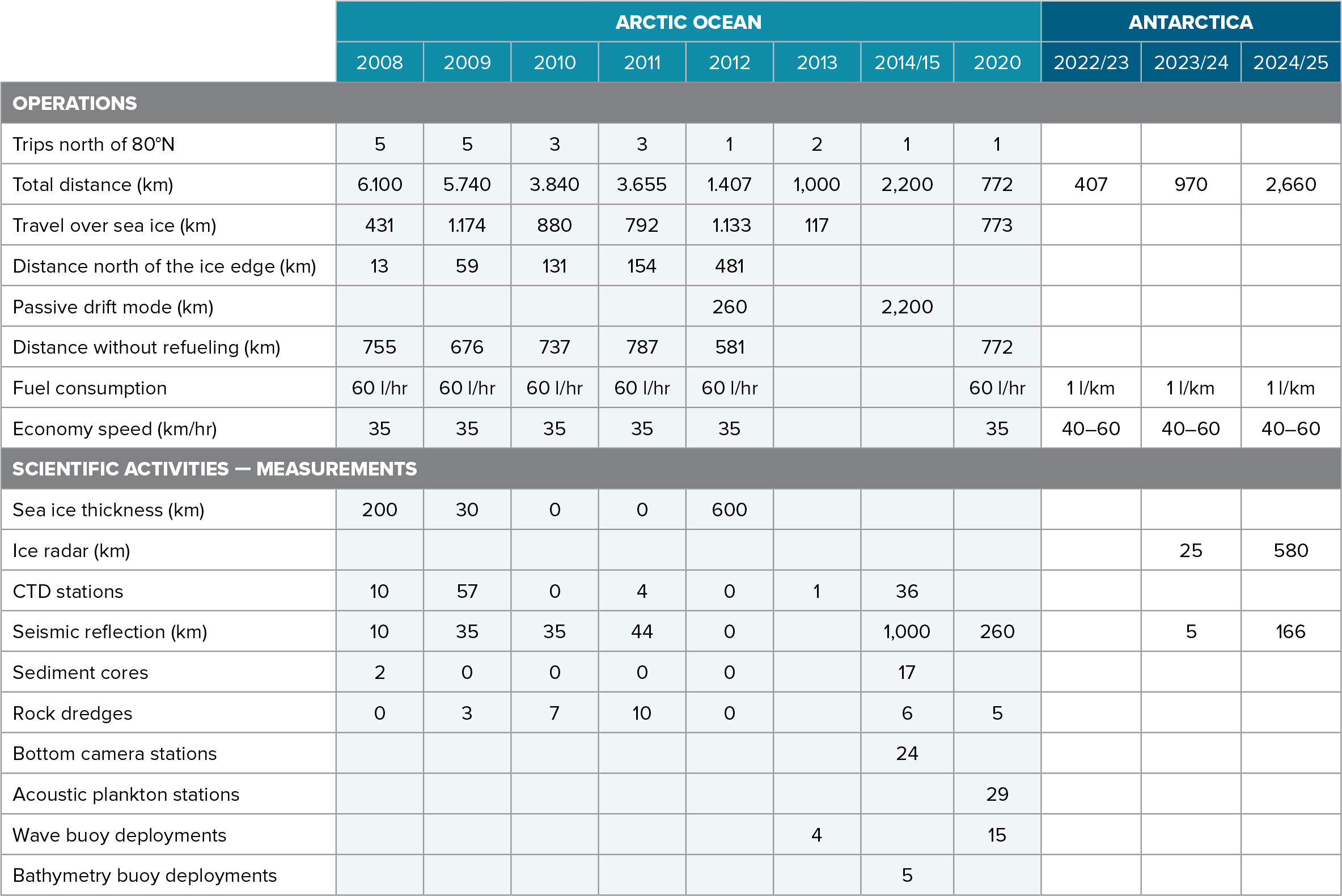

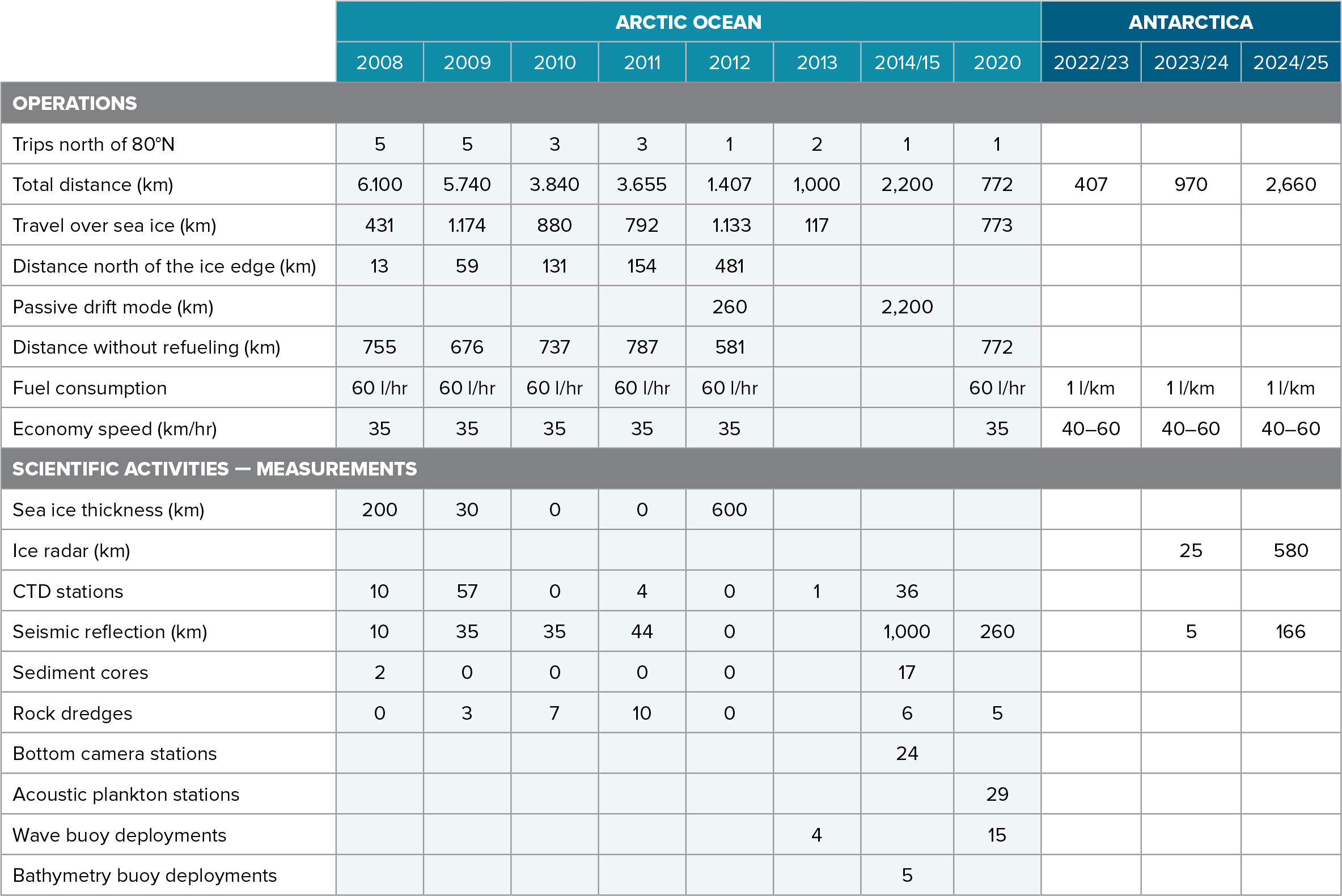

We report here on 12 seasons of operational experience with hovercraft in both polar regions. Table 1 summarizes the scientific activities in the Arctic Ocean using Sabvabaa, and details of the scientific results from Arctic Ocean expeditions can be found in the online supplementary material.

1 A hovercraft moves on an air cushion produced by a lift fan and contained by a skirt around the circumference of the craft. The air pressure inside the skirt becomes higher than the ambient air pressure and produces lift. As a result, the craft will float on the air cushion.

FIGURE 1. The hovercraft Sabvabaa is shown in different settings: (a) on the Fimbul Ice Shelf, Antarctica, December 2023, (b) floating at the dock in Svalbard, August 2010, and (c) as Fram-2014/15 ice drift station, 85°N, April 2015. When in ice drift mode, a tent annex provides workspace around a 1 × 1 m access hole through the ice. > High res figure

|

FIGURE 2. Photos show interior views of the hovercraft Sabvabaa cabin during Arctic Ocean operations in 2012 looking (a) toward the bow, and (b) toward the stern. Photo credit: S. Hendricks, AWI

> High res figure

|

TABLE 1. Overview of the operations and scientific activities undertaken using the hovercraft Sabvabaa. A list of publications related to hovercraft science operations is provided in the online supplementary material. > High res figure

|

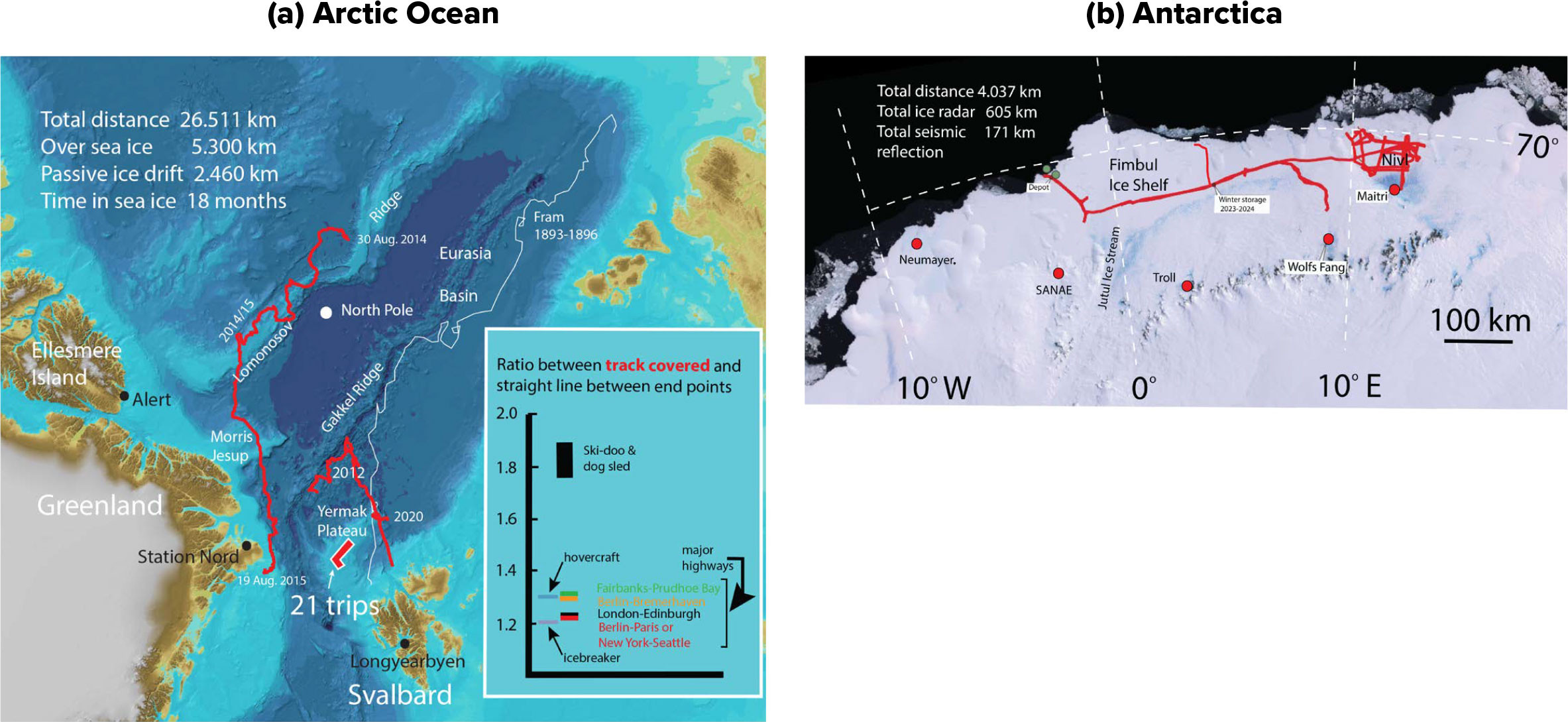

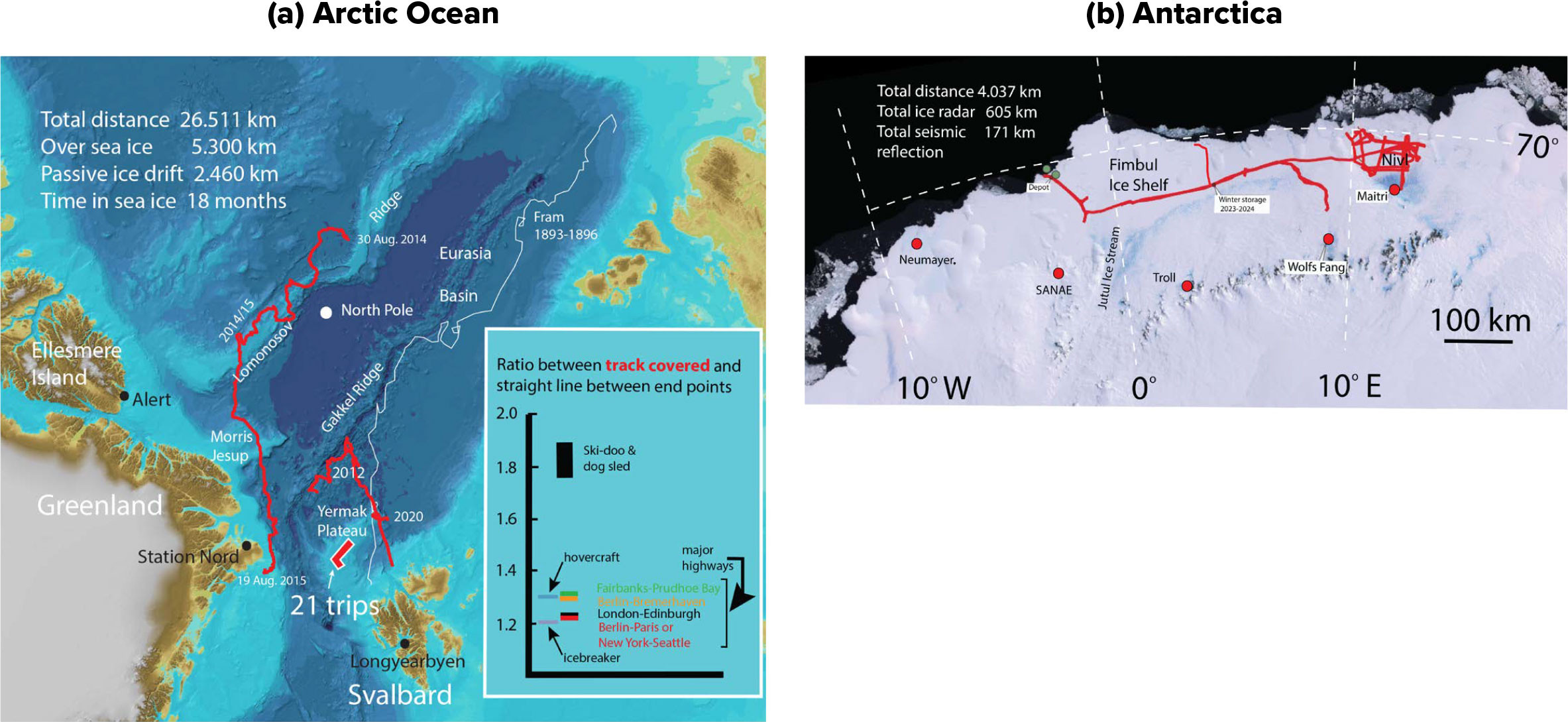

Operations Over Sea Ice in the Arctic Ocean

Griffon TD2000 hovercraft operations in the Arctic Ocean from 2008 through 2020 covered 26,551 km, of which about 5,300 km was over sea ice (Table 1, Figure 3). In addition, about 2,460 km was covered in ice drift mode. The activity included 19 unsupported (no refueling) and two supported successful trips from Longyearbyen, Svalbard (78°N), into the sea ice cover north of 80°30'N. Each unsupported trip started and ended with an open ocean transit of about 170 km. The longest unsupported trip out of Svalbard lasted three weeks and reached a distance of 150 km north of the ice edge.

FIGURE 3. Overview of the hovercraft operations (red track lines) described (a) in the Arctic Ocean and (b) in Antarctica. The inset shows a comparison of the efficiency of travel. Numbers for the track covered relative to the great circle distance for the hovercraft and the icebreaker are for travel between the ice edge and 85°N along 17°E in the Transpolar Drift. Numbers for Ski-Doo and dog sled include travel in both the Beaufort Gyre and the Transpolar Drift (Kristoffersen and Hall, 2014). Watch the accompanying videos in the flipbook version of this article. > High res figure

|

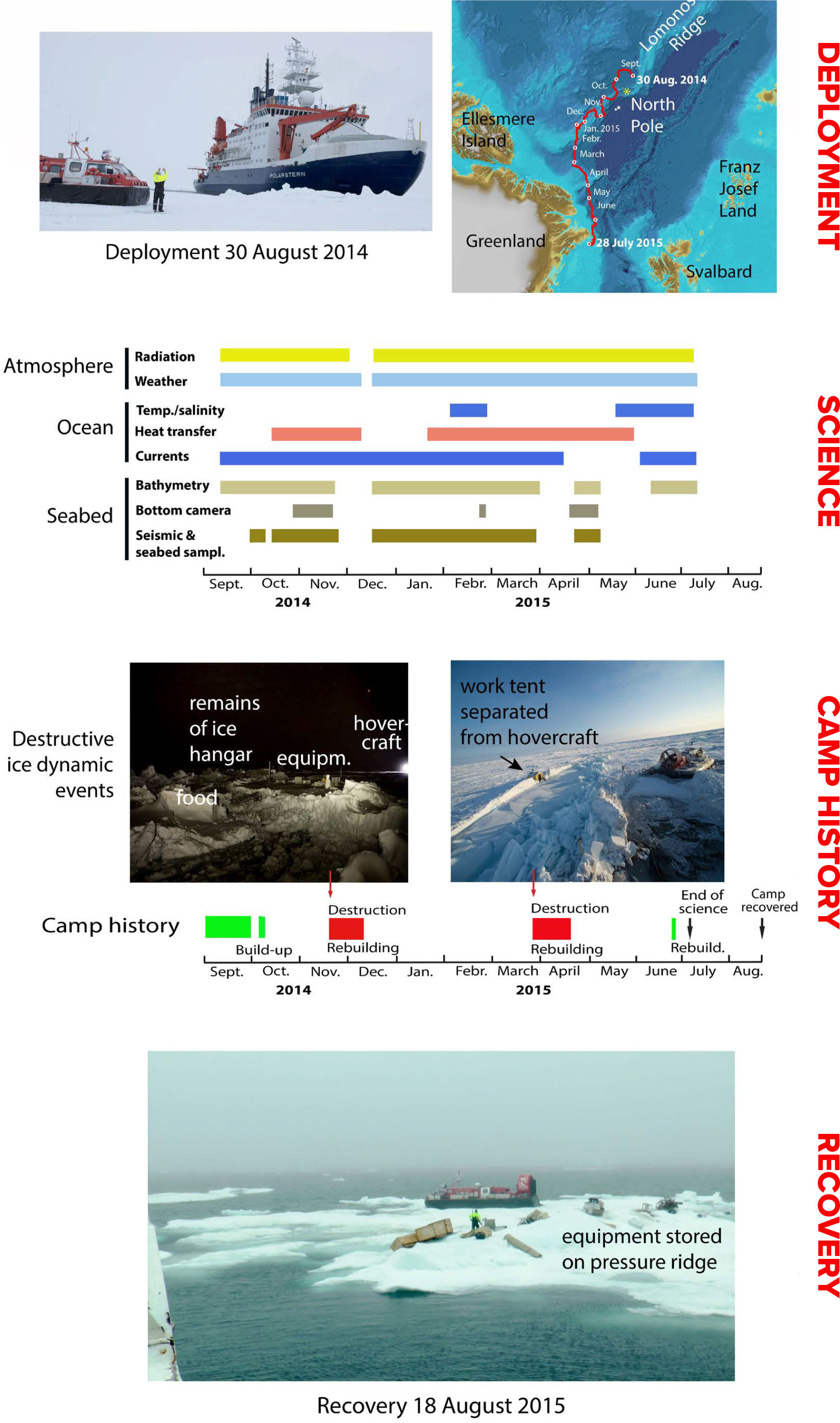

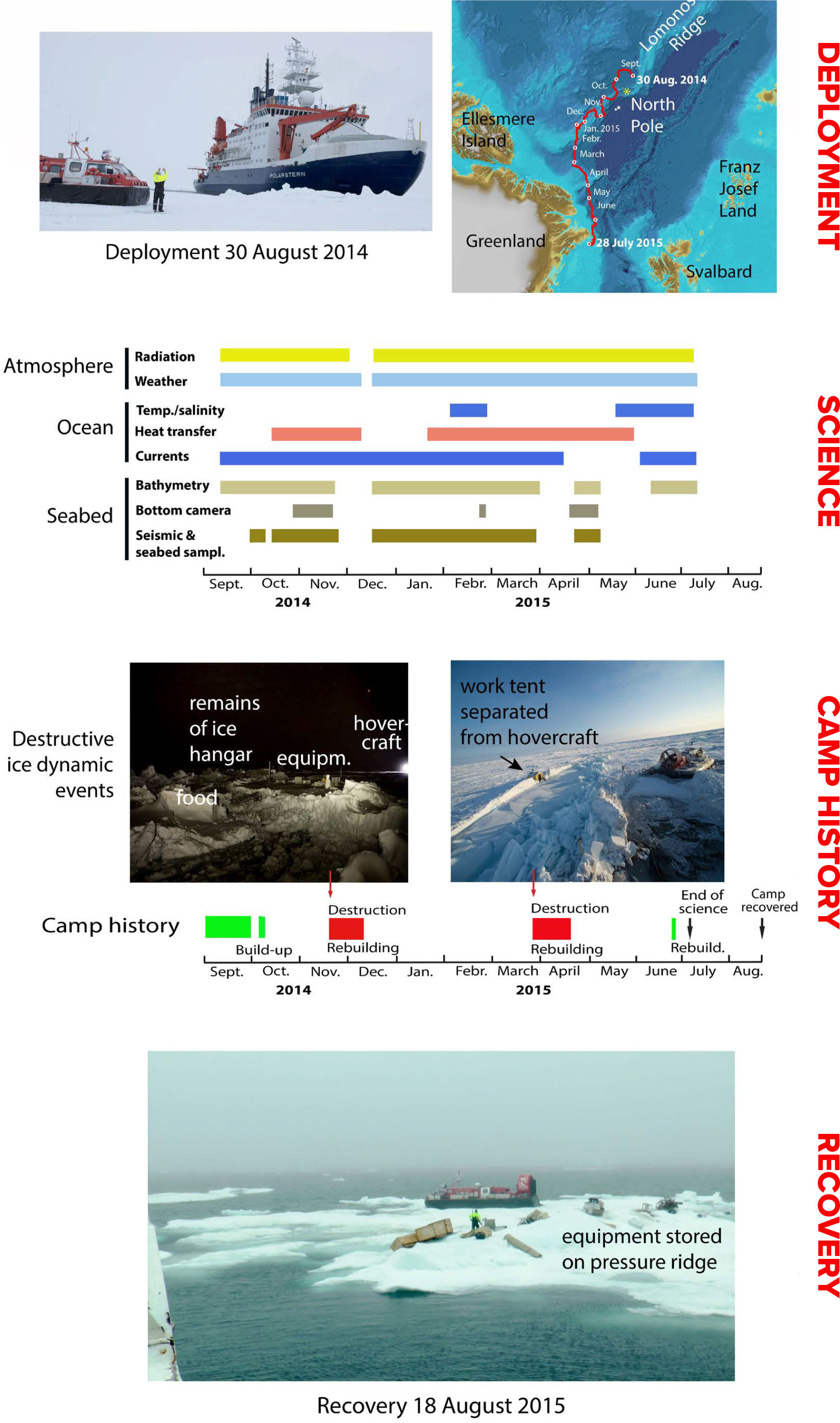

In addition to the 21 roundtrips (Figure 3) made from Longyearbyen (78°N) to an L-shaped target area on the Yermak Plateau (>80°30'N), the main scientific endeavors undertaken with the hovercraft were a three-month-long trip from Svalbard to Gakkel Ridge at 85°N in 2012 and a 12-month ice drift in the central Arctic Ocean in 2014/15. The icebreaker Oden accompanied the hovercraft in 2012. The target was Lomonosov Ridge, but the trip had to be aborted at Gakkel Ridge due to consistent poor light conditions and, eventually, time constraints. The return from Gakkel Ridge was with the icebreaker Polarstern. The subsequent 2,200 km, 12-month-long ice drift Fram-2014/15 was a joint venture between the German Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research and the Norwegian Nansen Environmental and Remote Sensing Center (Kristoffersen et al., 2016). Two support missions by a Norwegian Coast Guard P-3 Orion aircraft, and overflights by a Challenger CL-604 aircraft of the Danish Arctic Command, contributed to maximizing the scientific outcome of the endeavor. This is the longest drift on sea ice ever undertaken by Western scientists. Figure 4 provides an overview of the scientific activity and ice dynamic events during the ice drift.

FIGURE 4. Summary of events and scientific activities during the Fram-2014/15 ice drift. From Kristoffersen et al. (2016)

> High res figure

|

Hovercraft Considerations Over Sea Ice

On sea ice in the Arctic Ocean, the efficiency of travel, or trafficability (Hibler and Ackley, 1974), reflects the degree of ice deformation manifested by the number of pressure ridges that must be passed. Pressure ridges are often several meters high but have saddle points where a hover height as low as 0.5 m may be sufficient for passage. Here is where the standard, narrow hovercraft hull is an advantage. Hovercraft travel in the Transpolar Drift of first year ice can be achieved with an efficiency not very different from an icebreaker or transit on major highways on land between the larger cities (Figure 3a, inset). The effective advance toward the target may be 4–7 knots, varying with the abundance of obstructive pressure ridges (Kristoffersen and Hall, 2014).

The most critical issues for driving in sea ice are the light conditions and terrain definition. The early spring from end of March to mid-May have the best light conditions for aircraft and hovercraft operations in the Arctic. As the summer progresses, low clouds and diffuse light conditions (whiteout) become more prevalent, and by mid-August the visibility sufficient for hovercraft driving averages only a few hours per day (Kristoffersen and Hall, 2014).

Another consideration is the size of a hovercraft suitable for operating in the sea ice environment. Our experience is that a craft significantly larger (>11 m) and heavier (>7 tons) than the Griffon TD2000 is likely to be less versatile—it does not recover as easily from encounters with ice obstructions (Kristoffersen and Hall, 2014).

Hovercraft as an Ice Drift Platform

There are several advantages to using a hovercraft as an ice drift platform (Kristoffersen et al., 2016). First, the mobility of the accommodation and the instrument laboratory as one unit directly translates into safety. Second, the need for manpower is greatly reduced, making the hovercraft cost-effective to deploy. For example, ice dynamics forced four camp relocations during the Fram-2014/15 ice drift, two of which involved total destruction of the camp site and environs (Figure 4). In each case, the hovercraft was moved, instruments were recovered, and the operation was resumed after about three weeks. Total fuel consumption during the 12 months of the 2,200 km long Fram-2014/15 ice drift was equal to what an icebreaker burns in six hours of transit in heavy ice. For scale, an icebreaker transits from the ice edge at 80°N north of Svalbard to the North Pole (1,100 km) in about 7–10 days under good ice conditions.

Operations in Antarctica

Earlier Use of Hovercraft

Fuchs (1964) first proposed use of hovercraft for Antarctic travel, and New Zealand made the first trial run using a small air cushion pleasure craft in 1977 (Caffin, 1977). A more determined effort was pioneered by Japanese scientists who built and started testing an experimental hovercraft in 1981, followed by an Antarctic evaluation period running until 1990 (Murao et al., 1994). The 8 m long craft weighed 2.8 tons, had a 0.6 ton payload capacity, and a hover height of 0.6 m. The activity was not pursued further, as hovercraft technology was apparently not sufficiently mature at this stage. Seven years later, two small hovercraft with payloads of 300 kg were successfully used by the British Antarctic Survey on the Larsen B Ice Shelf to tackle a surface littered with melt puddles (James’ Hovercraft Site). During the 1988/89 season, the US Antarctic Program operated a licensed-built Griffon TD1500 hovercraft in McMurdo. The 10 m long craft was powered by a 190 Hp engine, could take a 1.5 ton payload, and had a stated hover height of 0.4 m. This craft operated on the Ross Ice Shelf and the adjacent sea ice in McMurdo Sound in support of science programs. Cook (1989) summed up the positive experience (see also https://www.southpolestation.com/trivia/history/hovercraft.html.

General Operational Experience

Sabvabaa operated on the ice shelf in Queen Maud Land between 2°W and 12°E during three seasons (2022–2025), traveling a total distance over 4,000 km (Table 1, Figure 3b). The effort was inspired by the positive experience at McMurdo 30 years earlier as reported by Cook (1989). Possible routes needed to be predetermined from satellite imagery to avoid areas fractured by active ice deformation associated with ice streams, the grounding line transition, or buttressing sub-ice topography.

The vast floating ice shelves have a level surface of hard blown snow with superimposed elongated dunes, called sastrugi, with wavelengths of meters to tens of meters. The dune amplitudes on the Fimbul and Nivl ice shelves were <1 m in scale, with regional differences. Following a snowfall or a storm, the snow surface hardens quickly from the diurnal heating and freezing cycles during the austral summer. The result is a surface with very low friction.

We used a load cell to measure the force (1,400 Newton) required to keep the ~8-ton craft in steady motion on the air cushion at the equivalent lift generated at cruising speed (1,700 revolutions per minute). This gave an estimated dynamic friction of 0.0175, which is about one-half the friction for skis against snow (Lang and Dent, 1982; Kondo et al., 2015). Low friction translates directly into a hovercraft fuel consumption of 1 liter per kilometer or less for transit over an ice shelf. This is about 50% of the fuel consumption required to drive the same craft over a flat ocean surface at the same speed. It is also 50% of the fuel consumption of other means of transport in Antarctica. Most importantly, the low fuel consumption extends the endurance of this hovercraft to well over 1,000 km for ice shelf missions with a science payload of about 1 ton.

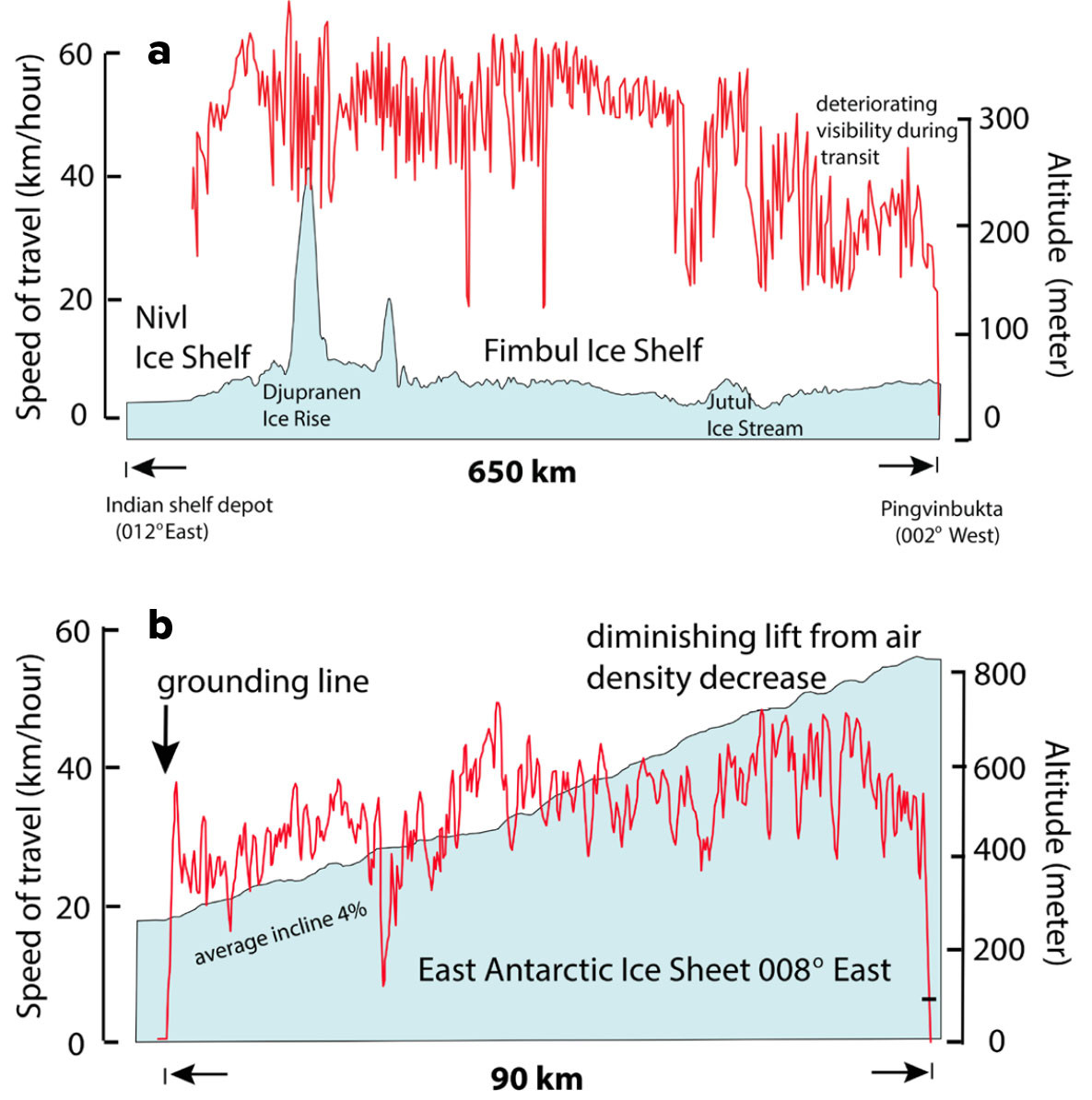

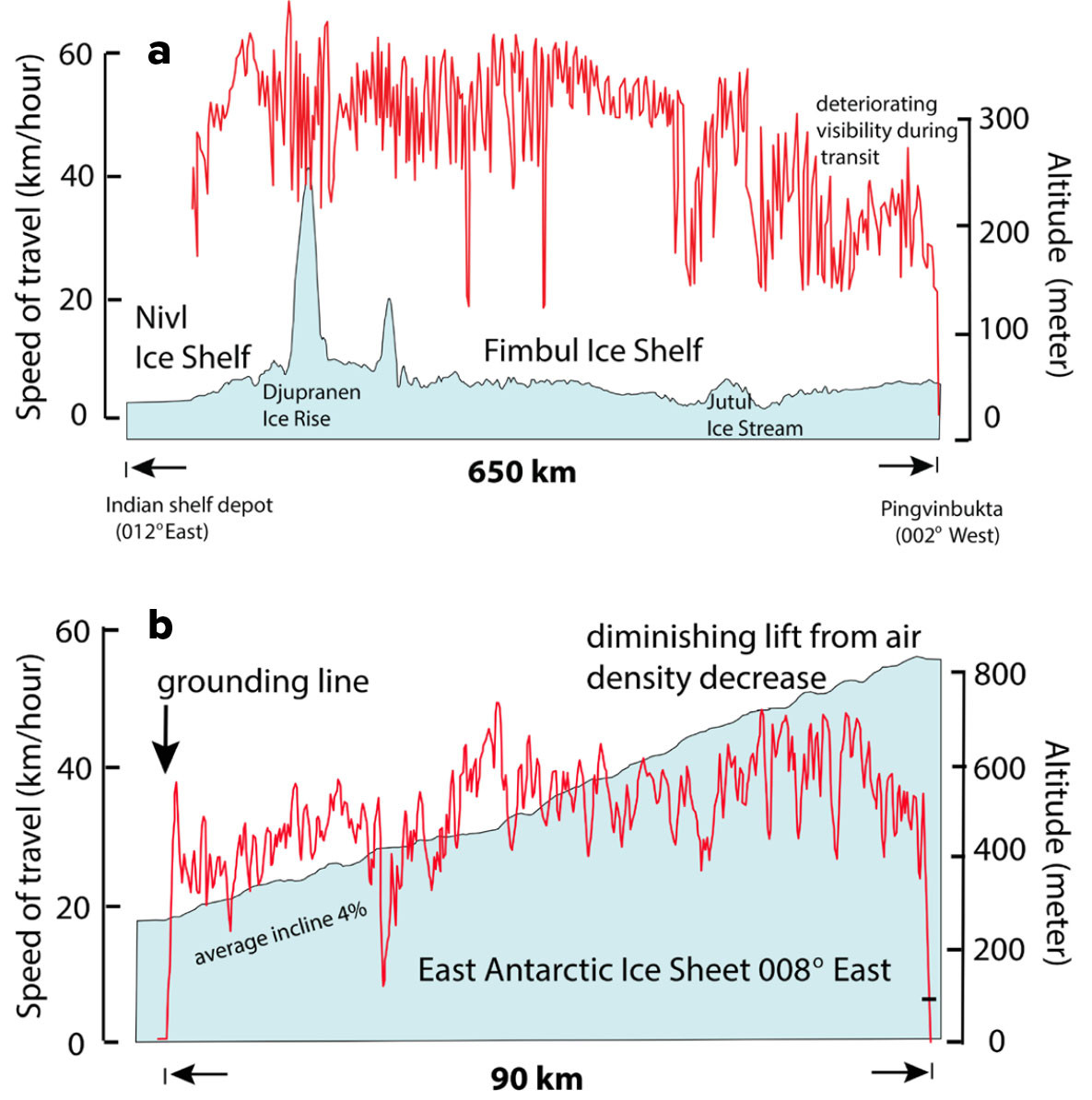

A conventional hovercraft is designed for operation at or near sea level. Because air density diminishes with increasing altitude, it leads to an operational limitation unless the lift power-to-weight ratio is increased. The Antarctic ice sheet at about 8°E in Dronning Maud Land landward of the grounding line has an average slope of about 4% (Figure 5b). This slope was readily traversed at speeds of 20–40 km/hr, but the hovercraft lift capacity gradually diminished with increasing altitude. Even at peak engine power, no lift capacity was left at about 880 m above sea level, where the reduction in air density was about 15%. As a result, the useful area of operation for this conventional craft design is below about ~700 m altitude. However, an experimental hovercraft operating at 1,886 m altitude on the Greenland ice cap had a ratio of lift power-to-craft weight about four times larger than the Griffon TD2000 considered here (Abele, 1966).

FIGURE 5. Hovercraft travel logs over ice shelves in December 2023. (a) Transit (650 km) from the Nivl Ice Shelf (12°E) in the east to the Fimbul Ice Shelf (2°W) in the west. (b) Ascent south from the grounding line toward Wolfs Fang runway along about 8°E. See Figure 3 for locations of panels a and b. > High res figure

|

Safe Travel

The hovercraft provides living facilities capable of enduring extreme Antarctic weather conditions. This advantage, and the low ground pressure combined with the length and speed of the craft, are factors that relate directly to safe travel on Antarctic ice shelves. The ground pressure per unit area of the hovercraft amounts to about 15% of a person in polar gear and contributes to safer travel than by any other means of Antarctic surface transportation. The length of the craft (11 m) and speed are also important for safe crossing of smaller cracks. Tests across 1 m wide open snow trenches on the ice shelf showed only minor loss of lift at speeds of the order of 10 km/hr. More extensive tests with a smaller craft (6 m long) at 1,886 m altitude on the Greenland ice sheet showed that a craft only 50% as long as our Griffon TD2000 Mark 3 could pass over 1.5 m wide trenches with ease at 40 km/hr (Abele, 1966). Thin snow bridges keep the air cushion contained and allow for crossing wider cracks.

Travel Comfort

The air cushion efficiently absorbs short wavelength surface undulations, and the comfort of hovercraft travel on an ice shelf compares well with the travel of a passenger car on a highway. The cabin noise comprises the hum of the engine and the propeller noise. We measured the noise level in the cabin to be 68 dB, comparable to a passenger car on a highway traveling at about 80 km/hr. An increase in sound amplitude by a factor of two corresponds to 6 dB, and a tenfold amplitude increase is equal to 20 dB on the logarithmic scale of relative sound energy levels.

Hovercraft Performance and Operational Costs

Mechanical Reliability

A hovercraft is mechanically simple, and its critical areas are easily accessible. The key components are the lift and propulsion system (engine, power transfer) and the neoprene skirt that confines the air cushion. Modern diesel engines can very reliably supply the power needed for driving in sea ice, which requires constant engine revolutions for lift, but continuously varying forward thrust to navigate a maze of irregular obstacles (ice blocks and pressure ridges). Constantly varying the thrust results in heavy stress on the components for transfer of power to the propeller. In contrast, driving in the Antarctic environment over a level snow surface is like regular use of a hovercraft in an ocean setting; the engine revolutions and the forward thrust are largely kept constant.

The neoprene skirt around the perimeter of the hovercraft confines the air cushion. It consists of a single upper part, and a lower part of 116 individual wear segments for tracking surface irregularities. Any possible damage to the skirt can be repaired in the field using a sewing needle and nylon thread or a stapler. For the hovercraft Sabvabaa considered here, about 40% of the lower skirt wear segments had been damaged beyond repair in the course of about 30,000 km of travel. We have experienced average hardware maintenance costs of less than $3,000/year, excluding an isolated incident of material fatigue in a bracing rod, which ruined the entire propeller duct and damaged the propeller.

We preferred to operate with a small crew of two during long deployments, so beyond the scientific agenda, we needed to master the skills needed for handling any mechanical and electrical issues that might arise. Technical advice from shore was readily available via satellite communication when needed. In rare instances (three times) over a total time span of 18 months in the sea ice, we have had spare parts jettisoned from an airplane (Kristoffersen et al., 2016). Our self-reliance during remote operations increased as the knowledge of past technical performance accumulated.

The hovercraft Sabvabaa has endured polar winters in the open from 2008 to 2025 with no specific degradation. In the Arctic, it was parked on the beach in Longyearbyen, Svalbard. In Antarctica, the craft was towed to the top of a >2 m high snow ramp with the front facing the prevailing wind. The main issue was proper cover of the engine bay to prevent influx of snow.

Safety in the Polar Environment

Meter-thick Arctic sea ice or Antarctic ice shelves may be considered terra firma in terms of carrying capacity. A minimum safe sea ice thickness of about 0.5 m is required for landing a four-ton ski-equipped Twin Otter (Stein, 1947). To the best of our knowledge, Russian, United States, and Canadian ice drift stations in the dynamic Arctic sea ice environment have not reported any loss of life specifically related to ice dynamics (Sater, 1964; Johnson, 1983; Frolov et al., 2005; Chartrand, 2006; Althoff, 2007; Kristoffersen et al., 2016; see also US Arctic Drifting Stations (1950s-1960s). From 1937 to the end of 2004, Russian scientists spent a total of 28.391 days on the ice and experienced of the order of 800 sea ice breakup events (Frolov et al., 2005). In 2013, the Arctic Council spearheaded an Arctic Ocean search and rescue agreement signed by all the circum-Arctic nations. This ensures coordinated attention in the event of any life-threatening situations, and improved satellite communication via Starlink is of great importance. The number of persons in a field party should be kept to a minimum, and any potential need for assistance should be defined by the field party rather than well-intended, shore-based assumptions of worst-case scenarios. While hovercraft mobility is an essential element of safety, a hovercraft expedition should include a back-up alternative for survival on the ice for at least a week.

Versatility

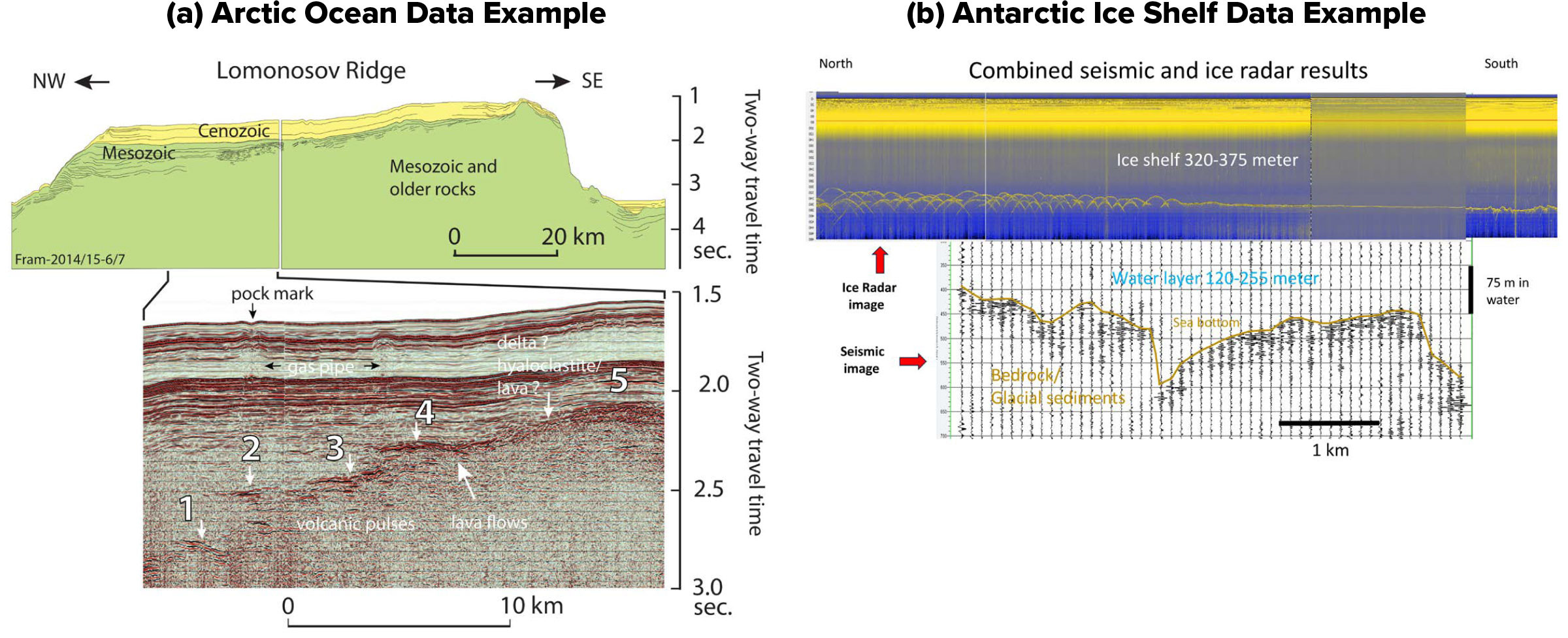

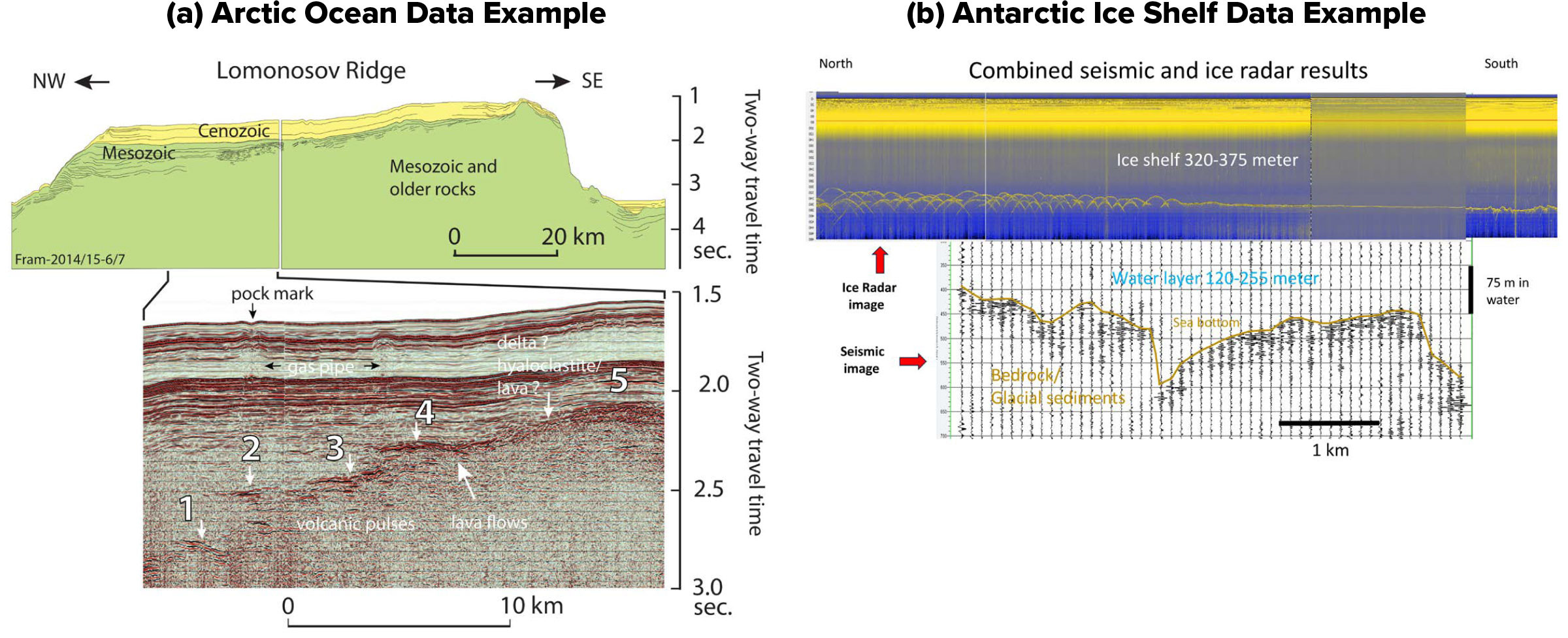

Although hovercraft payload capacity places limits on the scientific equipment, much can be achieved with equipment tailored to the tasks (Table 1 and online supplementary material). For example, in Antarctica, we towed an ice radar with a 20 MHz antenna at ~15 km/hr to survey the internal structure and measure the thickness of the ice (Figure 6b), and we used seismic reflection measurements to determine the thickness of the water layer below the several-hundred-meter-thick floating ice shelf (Figure 6a). Poulter (1950) showed that acoustic energy was most efficiently transmitted into the snow if the charge was fired at a distance above the surface rather than being buried in the snow. Poulter’s approach can be conveniently implemented in production mode by using the hovercraft platform to tow an air gun source and a string of eight geophones in a furrow to reduce the impact of wind noise (Figure 6a). We could comfortably achieve a seismic production rate of 2 km/hr at 100 m shot spacing to collect data that showed strong reflections from the seabed (Figure 7b). The combined ice radar and seismic observations across the grounding line constitute baselines for monitoring the large-scale dynamics of the Antarctic ice sheet.

FIGURE 6. Sabvabaa tows an air gun sled for (a) seismic reflection measurements, and (b) ice radar during a survey of the Nivl Ice Shelf in Antarctica in December 2024. See Figure 3b for location. > High res figure

|

In the Arctic Ocean, a hovercraft in ice drift mode using basic seismic equipment (<200 kg) with a small seismic source (0.3 liter) can obtain seismic reflection data (Figure 7a) of a quality comparable to, and of better resolution than, data acquired by an expensive icebreaker expedition (Mosher et al., 2013; Kristoffersen et al., 2016, 2021; Funck et al., 2022).

FIGURE 7. (a) Seismic reflection section across the Lomonosov Ridge (87°N) acquired during January 2015. The top section is a line drawing of the full profile, with an expanded view of the seismic reflection data within a 20 km interval of special interest below it. This seismic section documents the first evidence of Mesozoic volcanic pulses (numbered) on the Lomonosov Ridge (from Kristoffersen et al., 2023). (b) Seismic reflection (2 km/hr) results and ice radar measurements (15 km/hr) shown here were recorded on the ice shelf in Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica, using the hovercraft platform. These data demonstrate an efficient survey approach for obtaining information about seabed topography and water layer and ice shelf thickness. > High res figure

|

Endurance

Scientific trips normally carried up to 1,600 liters of diesel fuel in auxiliary deck tanks in addition to the regular fuel capacity of 900 liters, providing a total endurance of up to 40 hours at cruise speed. This amount of fuel is sufficient for zig-zag travel in the sea ice within the Transpolar Drift for a distance of about 500 km measured along a great circle end-to-end (half-way to the North Pole measured from Svalbard). Anything more ambitious requires cooperation with an icebreaker expedition for fuel resupply. In ice drift mode over a 12-month period with limited local driving, the Fram-2014/15 ice drift expedition consumed 15 tons of diesel drawn from supplies stored on the ice at the time of deployment. The amount of fuel needed for heating was about 10 liters/day. The endurance over ice shelves in Antarctica could be well over 1,000 km for a payload of about 1 ton (personnel and scientific equipment).

Costs

A field trip from the home port Longyearbyen, Svalbard (78°N), to the ice edge and beyond (80°30'N–82°N) as typically lasted up to three weeks at a cost of about $5k for consumables. The average annual maintenance costs was $3k and insurance $6k. The option of using a shipping opportunity for deployment at the ice edge (80°30'N) would require an additional $20k. No personnel costs are considered here.

The budget for the 12-month and 2,200 km long Fram-2014/15 ice drift joint venture was about $500k. Free hovercraft deployment in the Makarov Basin was made by the German icebreaker Polarstern based on a Memorandum of Understanding that included terms for data sharing and publication priorities (Figure 4). The Maritime Patrol of the Norwegian Coast Guard and the Danish Arctic Command contributed with air drops of spare parts to maximize the scientific output. Recovery off northeast Greenland was by a chartered seal hunting vessel.

The Antarctic operation was generated from an interest in revisiting the experience of hovercraft travel reported from McMurdo by Cook (1989). The endeavor was made in cooperation with the travel company White Desert Antarctica, which covered all the direct costs. The Indian Antarctic program provided logistics support for a scientific survey using ice radar and the acquisition of seismic reflection measurements on the Nivl Ice Shelf seaward of the permanent Indian scientific station Maitri.

The cost of building the Griffon TD2000 Mark 3 hovercraft Sabvabaa to our polar specifications in 2007 was about $1 million. Today, the estimated cost of a similar craft would be over three times this amount.

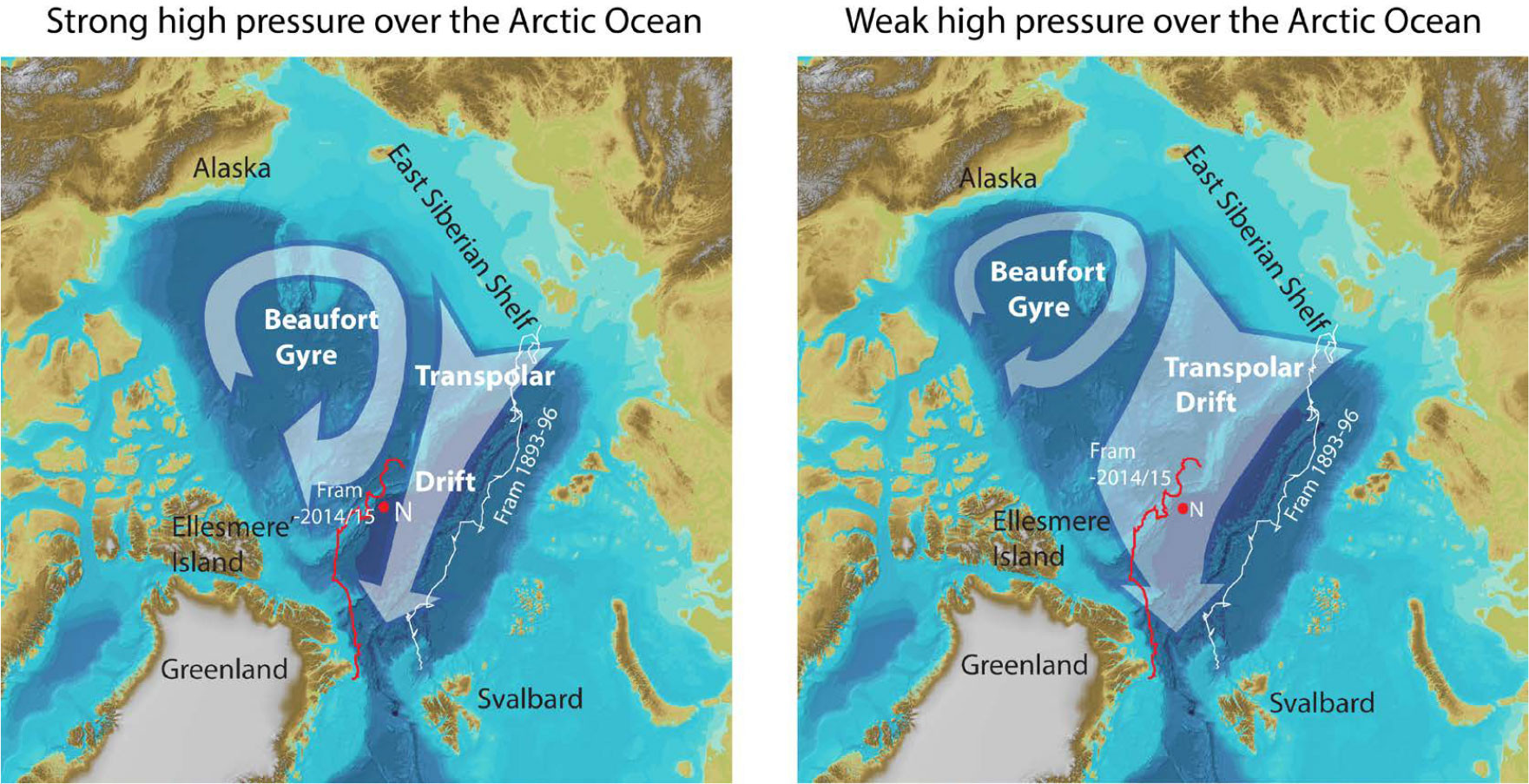

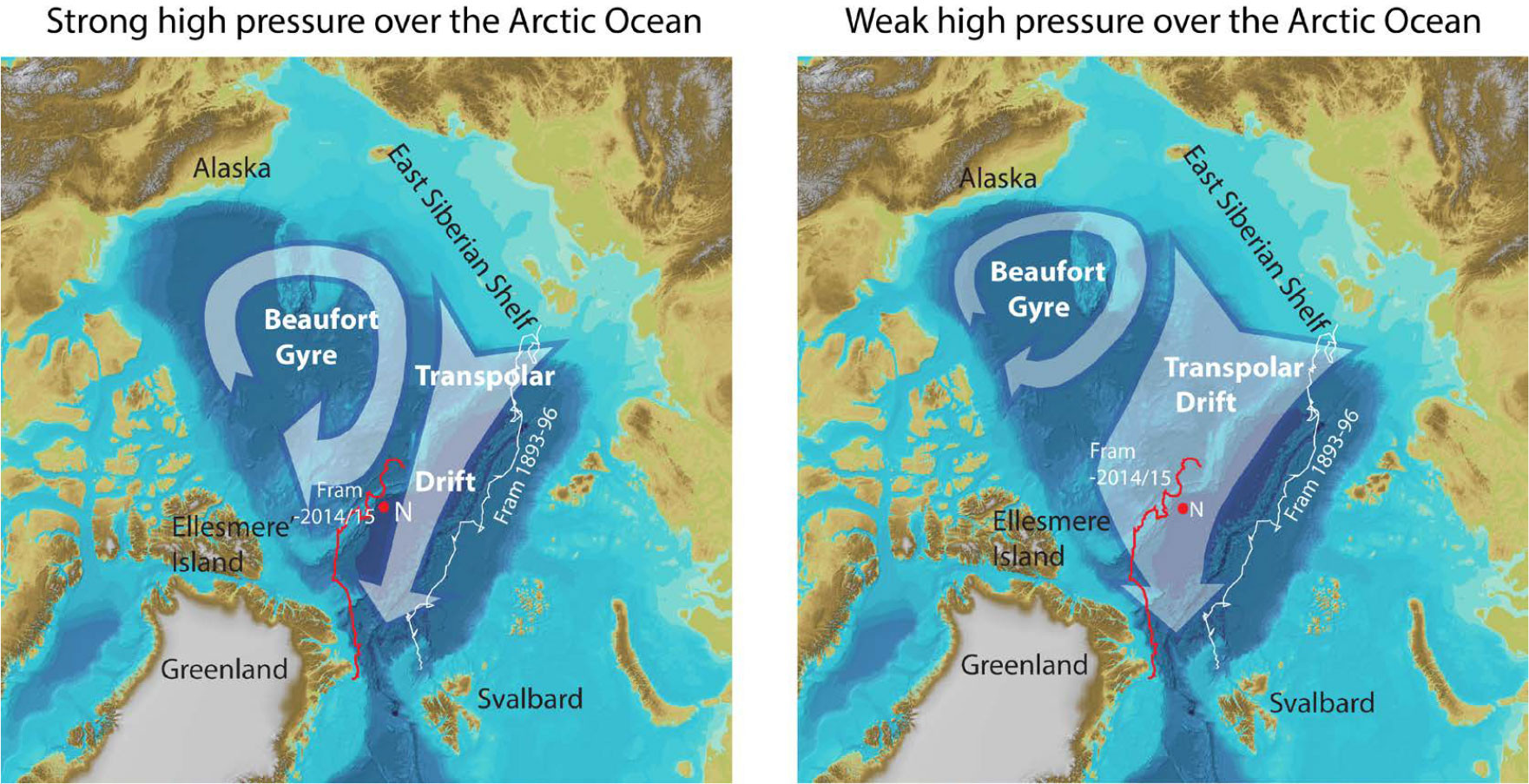

Access to the Polar Science Arenas

While large-scale sea ice circulation in the Arctic Ocean is determined by the prevailing high surface air pressure, the actual drift trajectories are strongly influenced by transient, fast-moving, low-pressure centers (Zubov, 1955; Colony and Thorndike, 1985; Frolov et al., 2005; Rigor et al., 2002). Young sea ice forms along the entire Siberian continental shelf, gets entrained in the periphery of the Beaufort Gyre, and feeds into the Transpolar Drift (Figure 8). These large fields of level ice with relatively few pressure ridges are amenable to the use of hovercraft. North of Canada and Greenland, sea ice motion reflects the buttressing effect of the land masses. This induces heavy deformation of the multi-year ice. These areas are off-limits for a hovercraft with a hover height as low as 0.5 m, but networks of recently refrozen leads will present opportunities for limited travel.

FIGURE 8. The large-scale pattern of sea ice drift in the Arctic Ocean in relation to the predominant surface air pressure (after Rigor et al., 2004). Traveling low pressures further modulate the air pressure field to induce temporary local ice drift excursions. The 1893–1896 drift of Fram is shown by the white track, and the red track follows the 2014–2015 drift of the hovercraft Sabvabaa. > High res figure

|

Transit to a particular study area in the Arctic Ocean can be accomplished by the hovercraft itself, deployment from a vessel at the ice edge, or within the ice from an icebreaker. We have successfully tried all these alternatives, but travel under the vessel’s own power over the open ocean from Svalbard (Ny Ålesund at 79°N) to the ice edge (at 80°30'N) became the general solution.

Operation in Antarctica will require cooperation with a national Antarctic research programs or a private operator for logistics and safety.

Conclusions

We have tested the concept of using an air cushion craft as a platform for science missions in both polar regions. The most successful pursuits have been good quality seismic reflection measurements in ice drift mode (1,389 km), rock dredges (31), CTD measurements (108), and video recording by towed bottom camera (14 locations for a total of 21 hours) between the North Pole and the continental shelf north of Greenland.

Hovercraft travel (practical hover height ~0.5 m) over the first-year ice fields in the Transpolar Drift can be achieved with the same progress as an icebreaker, although the fuel capacity limits the endurance to about 500 km. Hovercraft operations in the Arctic Ocean are the most cost-effective with deployment from an icebreaker and data acquisition in ice-drift mode, where hovercraft mobility is an important safety factor.

In Antarctica, travel with standard hovercraft is limited to operations below ~700 m altitude, as the craft lift capacity is based on the air density at sea level. Nevertheless, the extensive ice shelves framing the Antarctic continent represent the ultimate conditions for hovercraft travel on planet Earth. The Griffon TD2000 craft with a payload of 2.2 tons can deliver an endurance of >1,000 km over Antarctic ice shelves. The low hovercraft ground pressure (about 15% that of a human), combined with the length and speed of the craft, contributes to safer travel than by any other means of Antarctic surface transportation. For this reason, the hovercraft platform has a large and hitherto untapped potential for low-cost science missions on the Antarctic ice shelves.

Acknowledgments

The hovercraft Sabvabaa was acquired by Blodgett-Hall Polar Presence LLC. Operations in the Arctic Ocean have been funded by the Norwegian Research Council during the Polar Year and later by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate; Lundin Energy, Norway; and Axxis Geosolutions, USA. Logistics support for Antarctic operations was provided by White Desert Antarctica and the Indian Antarctic Programme, National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research. We gratefully acknowledge Arctic ice drift deployment support from the Alfred Wegener Institute for Marine and Polar Research, Bremerhaven; air support by the Norwegian Coast Guard and the Danish Arctic Command; logistics support from University Studies in Svalbard (UNIS) and Griffon Hoverwork Ltd., Southampton; and the unselfish effort of crew member Audun Tholfsen, to achieve maximum scientific output during the Fram-2014/14 ice drift. It would not have been possible to promote the hovercraft concept without the enthusiasm of Ola M. Johannessen, Andreas Heiberg, Gunnar Sand, Jørn Thiede, Harald Brekke, Geir Birger Larsen, Halvor Jahre, Patrick Woodhead, Vikram Goel, and Jan Erik Lie. Crucial electronic and mechanical support was provided by Ole Meyer, Gaute Hope, Hans Berge, Jostein Berge, and Russ Bagley. We thank John Gifford and Adrian Went of Griffon Hoverwork Ltd., Southampton, for prompt responses to our various needs over the years.