Introduction

Within ocean sciences, a persistent lack of inclusivity necessitates ongoing initiatives to encourage belonging, accessibility, justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (BAJEDI; Bernard and Cooperdock, 2018). Many existing structures and systems inhibit the full inclusion of minoritized groups, allowing inequity to persist in the field (Johri et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2024). Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensure a diverse, fair, and inclusive academic community and allow holistic ocean science research (Johnson et al., 2016; Johri et al., 2021).

To aid in addressing this issue, The Oceanography Society (TOS)’s Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) Committee began hosting interactive discussions at Ocean Sciences Meetings (OSM) in 2022. The 2024 event took the form of a town hall entitled “Scientific Societies’ Roles in Building Inclusive Communities.” To facilitate discussion, the town hall focused on three discussion questions:

- What are some successful models of expanding participation of minoritized and/or historically marginalized individuals in ocean and coastal sciences?

- What can be done to make ocean and coastal careers more accessible?

- How can we build a just and fair scientific and workplace culture?

During the interactive session, the 40 town hall participants shared ideas, engaged with peers, and provided anonymous written feedback on these questions and on topics related to the mission of the TOS JEDI Committee.

To assess the ongoing efforts of TOS and complement the in-person discussion, a brief survey was sent to TOS membership before OSM24, made available through QR codes to all OSM24 attendees, and is available in the online supplementary materials. The 13-question survey invited participants to share their lived experiences surrounding bias, discrimination, and perception of changes in the BAJEDI landscape in recent years. Survey participants provided optional demographic information. Write-in options were available for all demographic questions. Identifying information was not collected during the town hall, and survey responses were fully anonymized to facilitate participants expressing themselves freely. Here, we summarize the responses received from the community and highlight the use of community feedback to direct scientific societies, like TOS, toward effective approaches for broadening participation in ocean sciences.

Results and Discussion

Demographics of Survey Participants and Categorization for Analysis

The 2024 survey had 96 respondents, reflecting a 153% increase in response rate from a similar TOS JEDI survey carried out during OSM22 (Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2023). While considering the survey results, it is important to acknowledge that survey respondents and town hall attendees represent a self-selecting sub-population of the larger ocean sciences population. The OSM partner societies collected limited information on attendees. While the OSM24 demographic questions were more limited in scope than the optional demographic information collected as a part of the TOS JEDI survey, the self-reported gender of attendees shows that women and gender non-conforming individuals were overrepresented in the TOS JEDI survey population (60% and 3%, respectively) compared to the overall conference population (46% and 1%, respectively). Comparing the survey respondents’ career stages to overall OSM24 attendee career stages, graduate students were similarly represented (28% and 26%, respectively) and retirees/emeritus individuals were overrepresented (3% and 17%, respectively). All other career stages were underrepresented in the survey respondent group compared to the overall OSM24 attendee population: undergraduates (1% and 6%, respectively) and early to late career (54% and 67%, respectively). Generally, consistent collection of demographic information with uniform categories across institutions and professional societies will allow greater ability to assess equity efforts (Sturm, 2006; Hughes et al., 2022). Without this information, it is difficult to build robust, data-based metrics of success.

Responses to the survey were broken down into three groups based on self-reported, optional demographic information: minoritized individuals (54 respondents), heterosexual white women (19 respondents), and heterosexual white men (20 respondents). Three respondents who did not wish to provide demographic data were removed from this analysis. The survey used inclusive descriptions of men and women, and these categories may include cisgender, transgender, and gender-expansive individuals. A write-in option allowed transgender and gender expansive individuals who did not wish to be grouped in the binary “women” and “men” categories to self-describe their gender. All individuals falling outside of heterosexual white women and heterosexual white men are considered within the minoritized individuals category (i.e., non-white, non-heterosexual, and/or self-reported as belonging to a gender minority). Survey results were grouped based on these demographic delineations for two reasons. First, as the historically hegemonic group within Western academia, heterosexual white men are known to be less frequently exposed to prejudice and have fewer firsthand experiences with prejudice and discrimination (Liao et al., 2016). Second, while there has been an appreciable increase in equity and inclusivity for heterosexual white women in the geosciences over the past 40 years, minoritized individuals have not experienced a similar benefit over the same period (Bernard and Cooperdock, 2018). This is not to say that heterosexual white women do not still face significant barriers in academia, only that the barriers impacting individuals in this group compared to barriers experienced by minoritized individuals may differ significantly. Throughout this work, we use the terminology of Douglas et al. (2022), in which marginalized refers to a group that is devalued based on demographic identity, while minoritized refers to the negative experiences of underrepresented groups. Within this framework, heterosexual white women may experience marginalization, although they are not a strongly minoritized group in ocean sciences as a whole. As our limited survey population did not allow for a breakdown of specific minoritized groups, we present an aggregated analysis to maintain respondent anonymity.

Survey Responses: Perceptions of BAJEDI in the Ocean Sciences

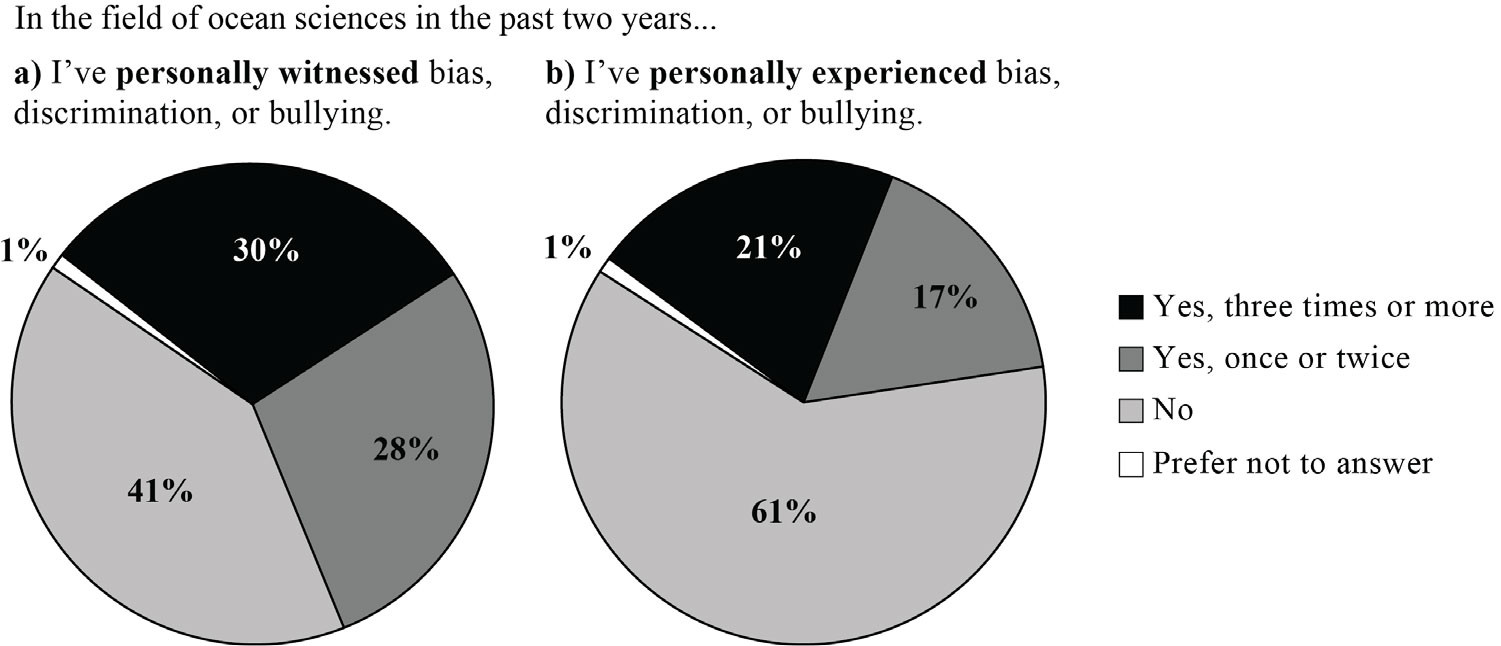

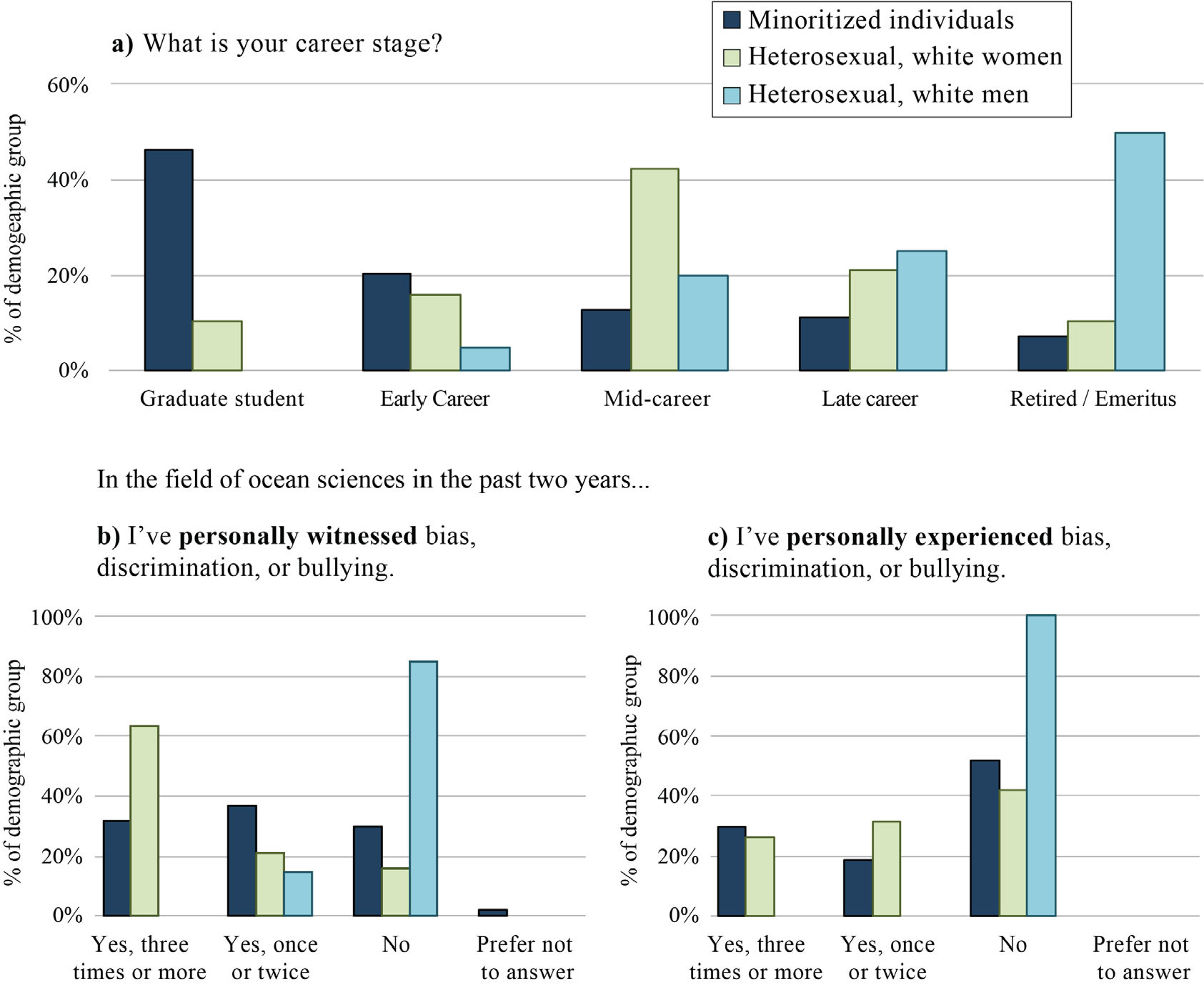

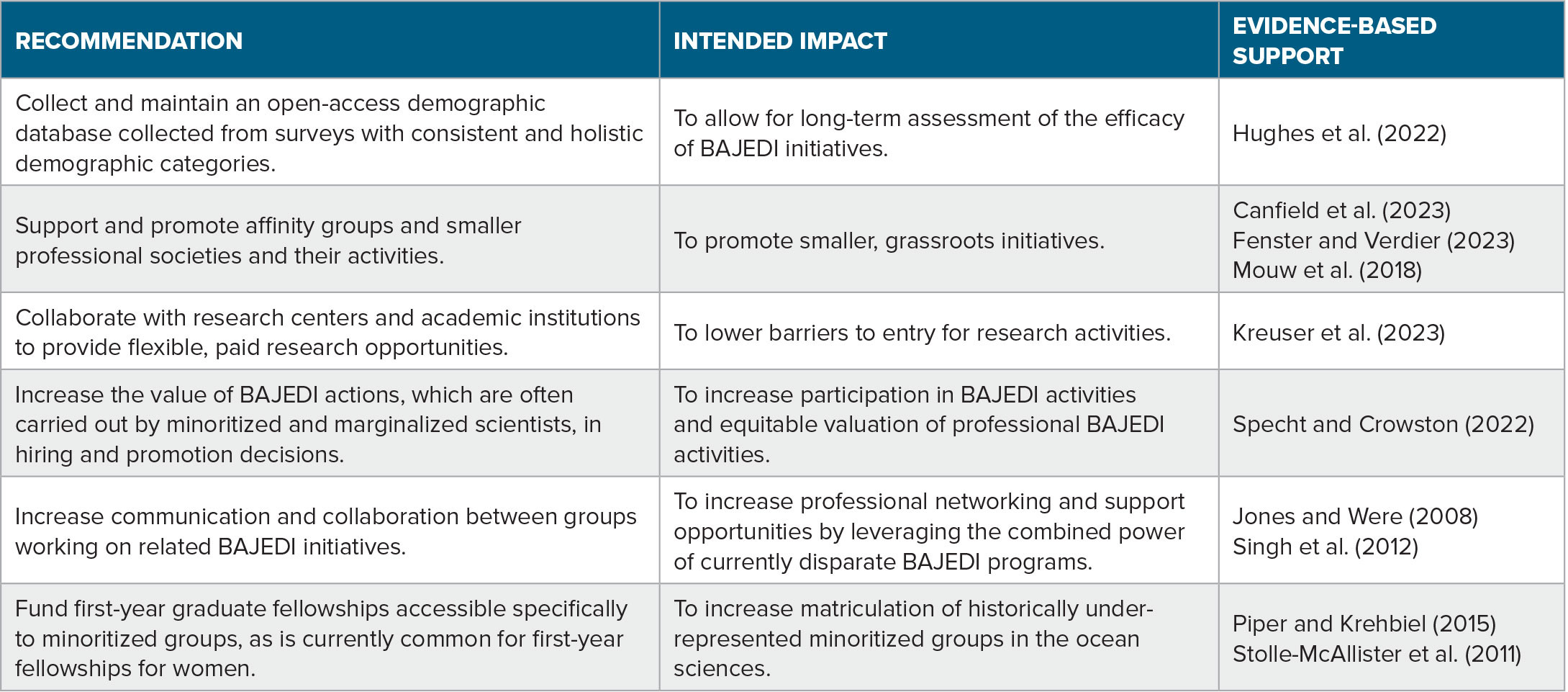

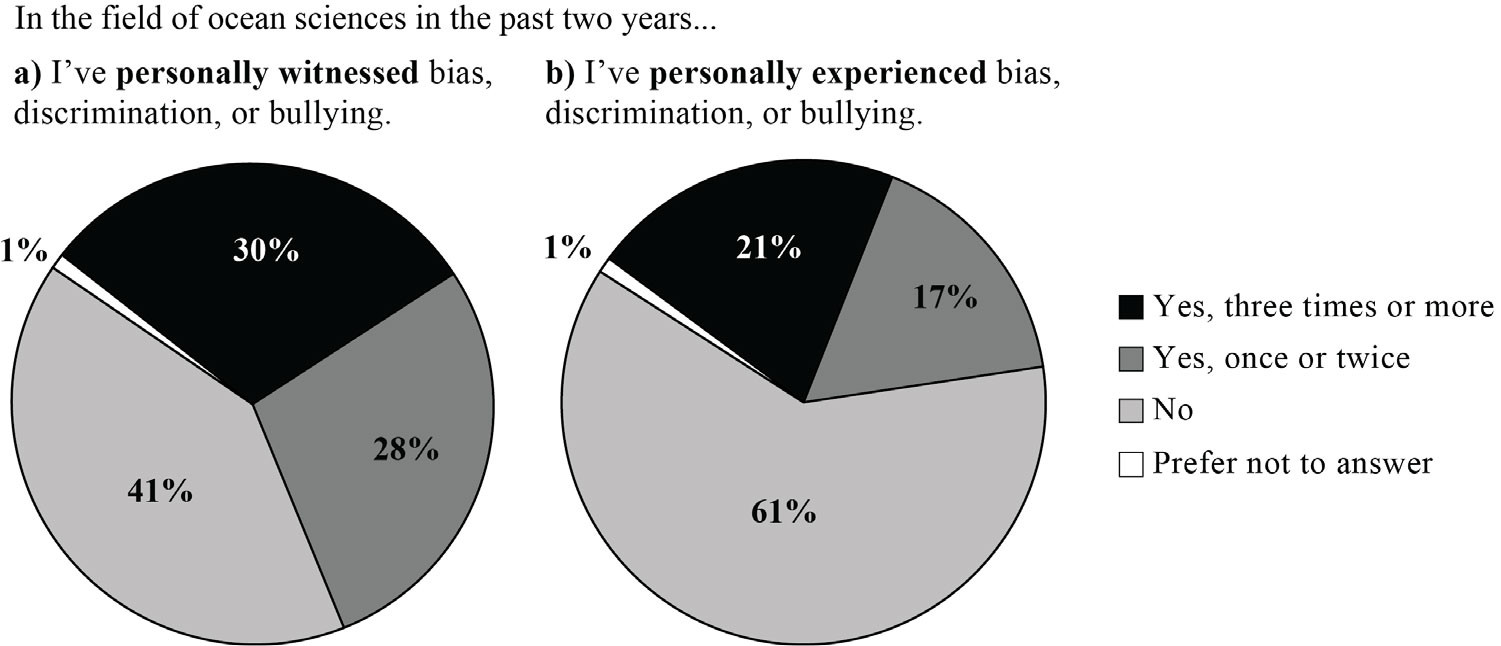

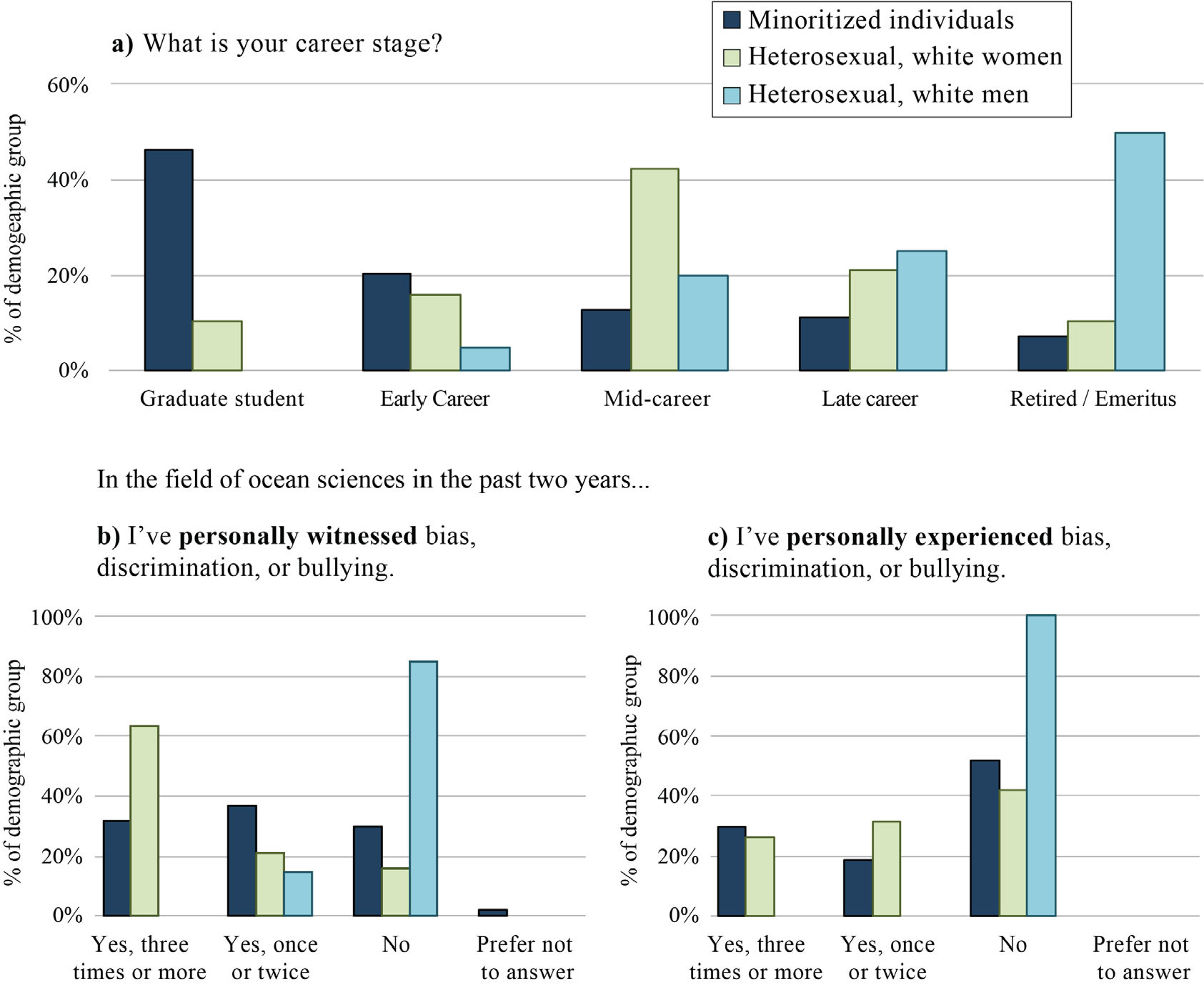

Survey questions 1 and 2 asked participants about their personal experience with bias, discrimination, and bullying within ocean sciences in the past two years. Most respondents had personally witnessed bias, discrimination, or bullying (58%, Figure 1a), and 38% of respondents had personally experienced such behavior over the same period (Figure 1b). Demographic composition at each career stage shows that survey participants in minoritized groups are currently underrepresented at higher career stages (Figure 2a). Of our survey respondents, 46% of minoritized individuals were graduate students. This declines at each stage, with minoritized individuals composing only 11% of late career and 7% of retired and emeritus faculty. Heterosexual white men showed the opposite trend, with 5% of this group at the early career stage increasing to 25% and 50% at the late career and retired/emeritus stages, respectively. Heterosexual white women show a largely normal distribution over the career stages, with the mid-career stage covering the largest period of an individual’s career. As OSM24 collected aggregated data that did not distinguish early, mid, and late career, it is difficult to compare these distributions with the overall distribution of career stages at OSM24. Therefore, assessing whether these distributions indicate personal perceptions within each group as to when BAJEDI work is most “valuable” professionally is outside the scope of this study. While the increased representation of minoritized individuals at the graduate and early-career stages is encouraging, a longitudinal analysis between 2007 and 2021 examining 55 ocean sciences graduate programs in the United States showed that while the recruitment of minoritized individuals into graduate programs has increased substantially, the graduation rate for this group has not concurrently increased (Lewis et al., 2023). Structural equity, which refers to the intentional design of institutional policies to minimize systemic bias and incentivize equity work, is necessary to remove existing barriers to the long-term retention of historically minoritized groups in ocean sciences. Specific examples of structural equity include funding first-year graduate fellowships accessible specifically to minoritized groups (as is common for first-year fellowships for women), requiring anti-bias training for advising faculty, considering faculty contributions to BAJEDI initiatives during tenure and promotion review, and funding equity-focused faculty chairs that offer salary support for BAJEDI work. While the demographic composition of career stages offers interesting trends, it is important to note that these results represent a limited sample and cannot be compared to the overall OSM24 attendee demographics, as information connecting conference attendee gender to career stage is not available.

FIGURE 1. Whole population responses from questions 1 and 2 regarding personal experiences and observations of bias, discrimination, and bullying within ocean sciences in the past two years in The Oceanography Society 2024 Ocean Sciences survey. > High res figure

|

FIGURE 2. Career stage distribution (a) and responses from questions 1 (b) and 2 (c) of survey respondents broken down into broad demographic categories. Minoritized individuals and heterosexual, white women both personally witnessed (b) and personally experienced (c) similar levels of bias discrimination, or bullying, and these rates were statistically greater than those witnessed or experienced by heterosexual white men. > High res figure

|

Survey results show that many individuals, particularly those in minoritized communities and heterosexual white women, continue to experience marginalization within ocean sciences (Figure 2b,c). On average, minoritized individuals and heterosexual white women personally experienced bias, discrimination, or bullying in the past two years at rates that were statistically higher than those experienced by heterosexual white men (48%, 58%, and 0%, respectively, Figure 2c; ANOVA F(2, 90) = 3.09, p ≪ 0.05). Similar results were seen when participants were asked if they had personally witnessed bias, discrimination, or bullying: minoritized individuals and heterosexual white women were significantly more likely to respond in the affirmative (69% and 84%, respectively), compared to only 15% of heterosexual white men (Figure 2b; ANOVA F(2, 90) = 3.09, p ≪ 0.05). Minoritized individuals and women reported statistically similar levels of both experiencing and witnessing bias and discrimination (Welch’s t-test, p > 0.05 in both cases). In general, prior studies have shown that minoritized individuals and women generally underreport incidents of harassment (Graaff, 2021). It is important to note that while minoritized individuals and heterosexual white women both reported high rates of both personally experiencing and witnessing discrimination, 85% of heterosexual white men reported that they had not witnessed any bias, discrimination, or bullying over the same period. These responses highlight a known phenomenon, whereby men are less likely than women to recognize instances of bias and discrimination (Davis and Robinson, 1991; Major et al., 2002; Drury and Kaiser, 2014; Liao et al., 2016) unless they have personally been the target of such behavior (Cech, 2024). Results from the survey indicate a continuing need for strategies to address systemic bias, discrimination, and bullying in ocean sciences. To that end, we now turn to the TOS JEDI town hall discussion and the resultant conversations on successful models for increasing equity, strategies to improve accessibility, and methods for creating a more just and fair culture within the ocean sciences community.

Successful Models

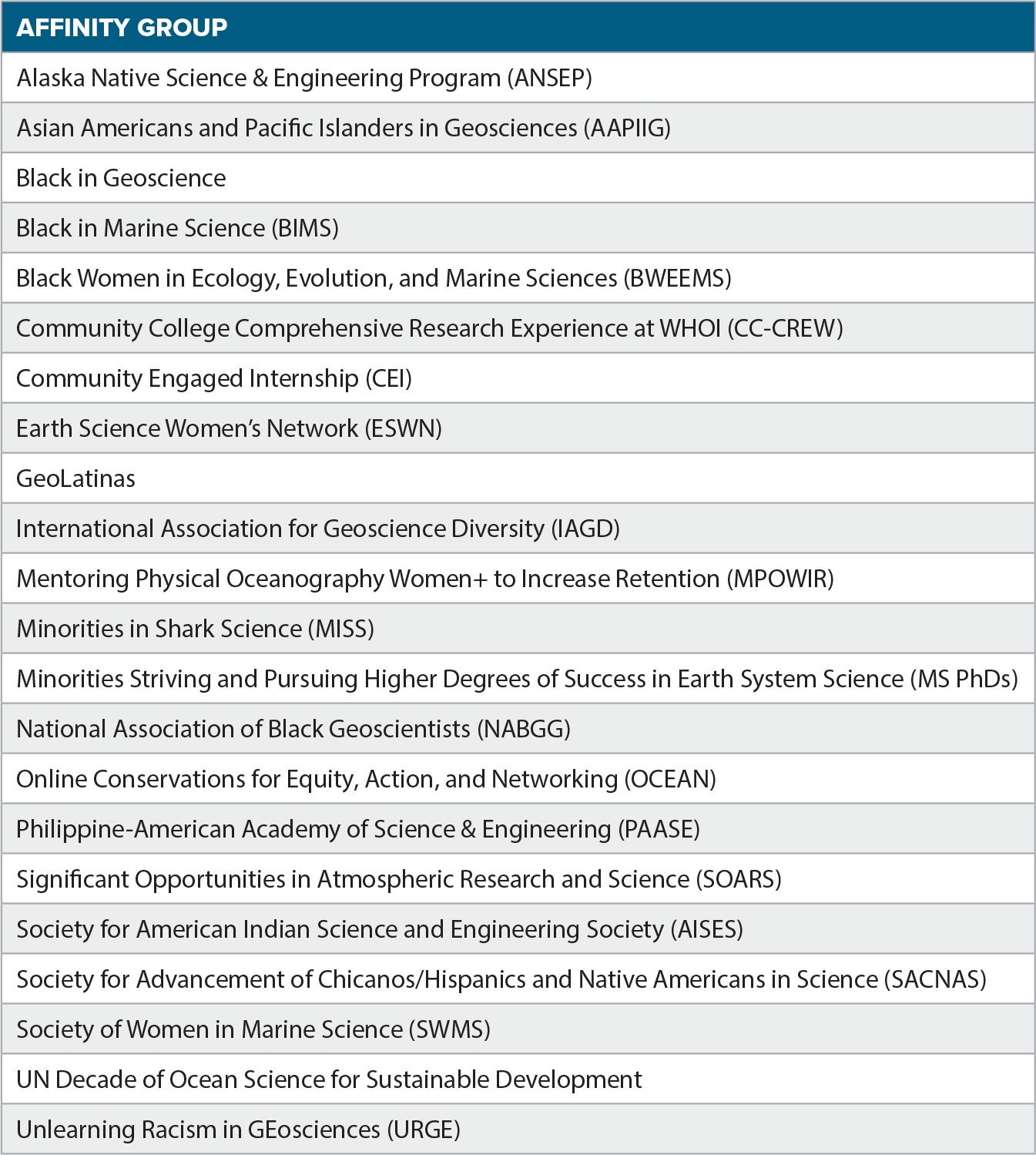

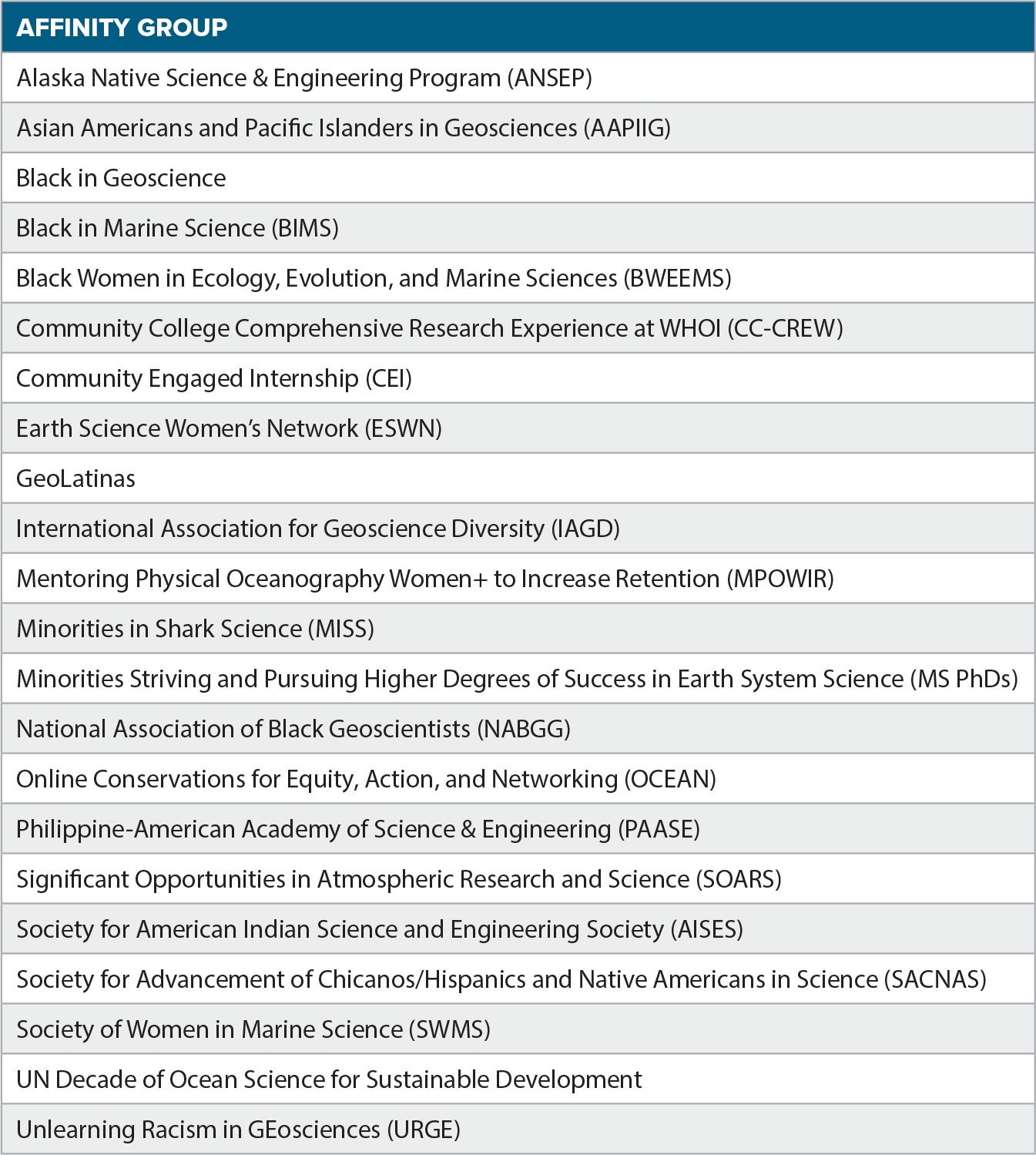

During the open discussion period of the town hall, one group of participants focused on the question, “What are some successful models of expanding participation of minoritized and/or historically marginalized individuals in ocean and coastal sciences?” Based on this discussion, we have compiled a list of known affinity groups supporting underrepresented researchers in ocean sciences (Table 1). This list has been expanded to include groups not discussed within the town hall; however, this summary should not be considered comprehensive. Finding community and building connections play crucial roles in increasing participation and retention (Canfield et al., 2023; Hansen et al., 2024). This pursuit also improves the quality of science produced, as more diverse teams have been shown to produce higher-impact science than demographically homogeneous teams (Freeman and Huang, 2014). Here, we include a few examples of groups at the forefront of attracting, supporting, and retaining individuals in ocean sciences to improve BAJEDI.

TABLE 1. Known affinity groups supporting underrepresented researchers in the ocean sciences. This list was compiled from the town hall discussion and expanded to include other groups not discussed within the town hall; however, this summary of groups should not be considered comprehensive. A more extensive list of affinity groups is available in Table S1 in the online supplementary materials. > High res table

|

Organizations focused primarily on attracting minoritized individuals to ocean sciences include the Online Conversations for Equity, Action, and Networking (OCEAN) project, which amplifies voices from marginalized groups within ocean sciences (Johanif et al., 2023), and Black in Marine Science (BIMS), which uplifts Black voices in marine sciences. These groups offer critical programs to attract and engage future scientists at the undergraduate level, or earlier. BIMS YouTube series airs weekly, engaging both adults and children.

Some groups focus more on supporting minoritized students during their academic careers by offering internships, professional development, and mentorship opportunities. Such programs include the Community College Comprehensive Research Experience (CC-CREW) at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Minorities in Shark Science (MISS), National Center for Atmospheric Research’s Significant Opportunities in Atmospheric Research and Science (SOARS), and Sea Grant’s Community Engaged Internship (CEI). MISS ran its pilot program “Diversifying Ocean Sciences Project” in 2023 with 100% of participants rating it as a valuable experience and noting that networking and feeling like they were part of a community were the most important experiences. Directed at undergraduates, Sea Grant’s CEI engages undergraduates and community college students in place-based research with an emphasis on local and Indigenous knowledge.

Finally, some programs focus on long-term community building to improve the retention of minoritized individuals. These programs include Black Women in Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Sciences (BWEEMS), Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS), Mentoring Physical Oceanography Women+ to Increase Retention (MPOWIR), Earth Science Women’s Network (ESWN), Society of Women in Marine Science (SWMS), and Unlearning Racism in Geoscience (URGE). BWEEMS and ESWN work to connect women, elevating their voices and supporting authentic connections with one another. ESWN, established in 2002, has an expansive network, connecting over 8,000 women. SACNAS, operating since 1973, supports scientists through multiple opportunities that include the National Diversity in STEM Conference (NDiSTEM), the “largest multidisciplinary and multicultural STEM diversity conference in the country” (Fenster and Verdier, 2023). MPOWIR focuses on the retention of women and minoritized genders, referred to collectively as women+ in the MPOWIR lexicon, in physical oceanography through organized mentorship and professional development opportunities beyond an individual’s home institution. As of 2018, MPOWIR reported that an impressive 80% of participants who earned their PhDs between 2005 and 2012 remained in the field (Mouw et al., 2018). SWMS, founded in 2014 and with over 460 members as of 2023, utilizes symposia, workshops, and webinars to engage women in a shared sense of community and belonging. This organization’s work has “demonstrated the effectiveness and importance of adaptive affinity-focused groups and events in ocean sciences” through analysis of their symposia (Canfield et al., 2023). The URGE program has been aiding the community in developing meaningful institutional programs since 2020, with specific directives toward educating non-minoritized individuals on the effects of racism on the retention of people of color in the geosciences, instituting collaborative institution policy reform, and sharing resources for consideration when designing more equitable institutional policies.

At an international level, frameworks like the Ocean’s Benefits to People (OBP) and the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) continue to support scientists in their career paths. OBP prioritizes the integration of local communities into ocean governance and policymaking (Belgrano and Villasante, 2020), while the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) presents a pivotal framework for BAJEDI efforts and initiatives in its goal to include diverse perspectives in ocean sciences (Polejack, 2021; Harden-Davies et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022).

In discussing support structures offered by affinity groups, town hall participants also touched on the disconnected natures of many programs. Group members noted that many BAJEDI programs operate independently, without unifying, inter-institutional structures. Group members felt that unifying structures, particularly for programs focused on undergraduate education and retention, would provide greater community support and professional networking. The idea of a unifying, inter-institutional structure was underscored by another core topic that focused on the necessity of strong cohort building within equity programs. Here, cohort refers to an intentionally organized group for a minoritized and/or marginalized community that progresses through education stages together (e.g., a cohort of graduate students of color who begin a graduate program the same year). Individuals who participate in the cohort may have shared life experiences related to their minoritized identity and may face similar experiences of inequity in ocean sciences. To build strong cohorts, the group’s discussion identified three guiding tenets: (1) offer individuals facilitated networking opportunities, (2) remove financial barriers to participation, and (3) engage in robust post-program follow-up and continued engagement with cohort members. Within STEM, cohorts focused on retention of minoritized individuals are shown to be successful when multi-avenue support structures are available (Hansen et al., 2024), as seen in the high retention rate (80%) of the cohort-focused MPOWIR program. Within MPOWIR, early-career participants are grouped with similar career-stage peers at different institutions than their own, and two senior leaders convene monthly group mentoring over the course of two to three years. This continuity in mentorship through career transitions positively supports retention of women in the field (Mouw et al., 2018). The Possee Foundation is another excellent example of a unifying, inter-institutional structure that specifically focuses on cohort-based retention strategies. The Posse Foundation works with dozens of undergraduate institutions to improve the retention of students of color in STEM fields, including post-program community engagement, and boasts an impressive 90% graduation rate for students in its programs (The Posse Foundation, 2024). Initiatives focused on expanding the participation of minoritized groups continue to grow, with numerous programs emerging to address inequities in ocean sciences since 2020. Mirroring the increase in programs directed toward improving participation in ocean sciences, 60% of publications related to ocean equity and justice have been published since 2020 (de Vos et al., 2023). While this recent focus on equity initiatives is encouraging, it is important to acknowledge that the actual efficacy of this groundswell can be difficult to measure, as long-term holistic demographic information is rarely publicly available.

Accessibility

Scientific institutions continue to implement initiatives to improve BAJEDI within their communities. These include, but are not limited to, more equitable hiring criteria and recruitment practices, implementing codes of conduct, restructuring tenure review to value equity work, and creating safe spaces for marginalized identities, such as LBGTQIA+ spaces. Professional societies play roles in these actions by providing safe spaces within chapters, highlighting the work done by affiliated groups, and providing equity models for individuals and institutions to implement. While these initiatives can help make ocean careers more accessible, and professional societies have done work to make these spaces and policies more readily available, accessibility remains a challenge. Responses to the OSM22 survey suggested that gatekeeping was the most significant challenge to diversifying the ocean sciences (Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2023). Gatekeeping refers to the intentional reduction of access to professionally beneficial activities, particularly by limiting marginalized and minoritized groups. Early engagement, free from gatekeeping, is critical to increasing access to ocean sciences. Early engagement should be supported by equitable access to meaningful professional development experiences through paid internships (Kreuser et al., 2023) and more flexible introductory research opportunities.

The survey and group discussions also touched on factors outside an institution that impact the possibility of successful BAJEDI programs. In particular, groups discussed how regional and national political agendas may hamper efforts to improve equity. Nearly one-third (27%) of the OSM24 survey respondents live in a region with anti-BAJEDI legislation, 43% live in regions currently unaffected by such legislation, and 30% were unsure of the local legislative atmosphere. Much of the discussion within this breakout group focused on strategies to make ocean careers safe for minoritized individuals in light of these political and legislative landscapes. Participants suggested having open conversations with visiting scholars before their arrival and with applicants during the application process. These may be facilitated by a brief survey to prospective professional visitors to an institution, which could ask guided questions on what types of information the visitor would be interested in being briefed on (example topics include results from previous institution climate surveys on the experience of minoritized groups at the institution, and LGBTQ+ topics, including the availability of health care). Upfront discussions would allow individuals to pick environments where they can expect to live safely, even if that may mean turning down opportunities. Institutions should also actively advertise resources available to assist individuals, including appropriate safety policies, reporting measures, and health resources. This information should be readily available to current and prospective employees and students. Required training for principal investigators on the socio-political conditions in geographic regions new to their lab (e.g., visited for conferences, fieldwork) will aid in preparing for unfamiliar legislative landscapes. Principal investigators are responsible for educating all trainees on safety in these regions in order to protect their direct reports and affiliates.

These issues are broader than ocean science and STEM careers, with significant backlash against DEI progress, increasing legislative attacks aimed at transgender and gender-expansive communities, and the elimination of federal DEI resources by the US government in January 2025, subsequent to the writing of this article. Ensuring safe working environments for all individuals, particularly in our current socio-political climate, was of top concern among our town hall participants. In addition to addressing barriers to access, the ocean sciences community must take a leading role in fostering safe and equitable access to places and spaces unique to the field, including shipboard, coastal, and remote environments (for an example, see McMonigal et al., 2023). Discrimination is still happening at the institutional level and should be openly acknowledged. Institutions can and should put resources in place to protect their workers and students. Furthermore, institutions and colleagues can advocate for safe and inclusive legislation as it pertains to their working environments.

Just and Fair Culture

As we strive for an increasingly inclusive ocean sciences community, the importance of retention cannot be overstated. Standing in the way of retention is a disconnect between the lived experience of minoritized individuals and recognition of this lived experience by individuals who are not marginalized or minoritized. Participants in this town hall reflect this divide. As shown in the OSM24 survey results and previous studies, groups who do not experience systemic prejudicial bias, in this case, heterosexual white men, appear to be less aware of the lived experiences of gender and racial minorities (Figure 2b,c; Davis and Robinson, 1991; Major et al., 2002; Drury and Kaiser, 2014; Liao et al., 2016). The survey data demonstrate that minoritized individuals and white heterosexual women experience greater marginalization through bias, discrimination, and bullying (Figure 2c). Increasing awareness of the lived experiences of those on the receiving end of such behavior may strengthen understanding in the community, particularly for those who do not personally experience significant marginalization themselves, and increase a sense of belonging for marginalized scientists.

To begin addressing this issue, town hall participants suggested policies at the institutional/organizational, government agency, and professional society levels. Participants discussed how recent shifts in academic culture have resulted in appreciable advances in structural equity at the agency and institutional levels. Institutional policymakers have the power to propel culture change by examining existing policies and evaluating those policies from a BAJEDI perspective. Discussion group members reflected on the need to uplift the voices of minoritized groups during policy evaluation and reform. Scientists directly impacted by such policies should feel ownership in improving them. To this end, it is essential to center the voices of marginalized groups in reforming inequitable policies, recognize equity work in performance reviews, and ensure measures for accountability.

Promoting BAJEDI in ocean sciences will require a change in resource allocation, hiring, promotion, tenure evaluation, and recognition systems. Outdated academic productivity metrics center almost exclusively on funding acquisition, paper production, and impact factors, with little or no regard for historical intersectional layers of oppression that unequally impact marginalized groups. For example, much of the work focused on BAJEDI topics is executed by the very minoritized and marginalized individuals most affected by systemic inequity (Kamceva et al., 2022). There is little recognition for these efforts, despite the overall benefit to the community through the creation of more diverse teams, which are known to produce better science (Freeman and Huang, 2014). The actions and initiatives that bring people together, build community, and ultimately advance science are overlooked and undervalued in promotion and tenure processes (Specht and Crowston, 2022). Broadening metrics to include service to affinity groups and incentivizing mentoring options beyond traditional advisor/advisee relationships would more accurately celebrate the various types of contributions that are meaningful to the success of the scientific community. There was general consensus among town hall attendees that focusing on building community, increasing awareness, and supporting cultural change with openness and curiosity would allow for more inclusive, equitable policies. Reviewing the present system and broadening achievements beyond scientific work would foster a more just, equitable, and resultantly inclusive academic community.

Conclusions

Survey results and input from participants at the OSM24 town hall present a picture of an ocean science community actively attempting to address persistent inequity within its ranks. A great deal of work is still needed to achieve equity and foster a sense of belonging and inclusivity for historically minoritized and marginalized groups. Survey responses from members of the ocean sciences community point to increasing inclusivity but continued challenges, including inequitable representation of minoritized groups, lack of inclusive research opportunities, and antiquated academic productivity metrics. The rise of more professional societies, affinity groups, and other organizations that support diverse people participating in ocean sciences was identified as a major strength by town hall participants. Larger professional societies can support smaller affinity groups by raising visibility, encouraging inter-group professional networking, and highlighting their achievements in national publications. Table 2 provides an overview of the major action item recommendations.

The current lack of publicly available demographic information continues to hamper the transparent assessment of BAJEDI initiatives. Without these data, it is impossible to assess changes in the demographic composition of the ocean sciences community as a result of BAJEDI-focused programs. Instituting an opt-in model to collect such data from professional societies and conference attendees would be a useful step toward closing this data gap. Collecting and analyzing demographic data would allow better understanding of the efficacy of current BAJEDI initiatives and implementation of data-driven improvements. Greater collaboration with social scientists and higher education researchers is needed to accomplish this work in a just, fair, and robust manner. In addition to thoughtful data collection and analysis, organizations and professional societies need to critically and carefully consider how to store and use demographic data, as it may have personally identifiable information. Furthermore, organizations and societies should collaborate to ensure use of consistent categories and data collection methods across surveys, as is common in large-scale data inter-calibration efforts within the ocean sciences. As responsible stewardship of data requires financial resources, we encourage professional and scientific societies to seek funding for this purpose.