Full Text

Imagine entering a classroom with your arms full of portable whiteboards. A student looks up, smiles broadly, and says, “Yes—more sketching today! I really enjoy these exercises!” This happened recently in an undergraduate oceanography classroom. Here, we want to share our experiences with collaborative sketching to support students’ sensemaking.

As teachers, we want our students to make sense of how various ocean processes or systems work. Sensemaking is “a dynamic process of building or revising an explanation in order to ‘figure something’ out” (Odden and Russ, 2019). But, where does sensemaking happen in the learning process, and how can we support it? Two metaphors are commonly used to describe learning: “knowledge as acquisition” or “knowledge as participation” (Sfard, 1998). The importance of participation has been stressed in the literature under the umbrella of “active learning” (e.g., Deslauriers et al., 2011, 2019; Freeman et al., 2014).

A third metaphor focuses on “objects of knowledge” (Knorr-Cetina, 2001)—physical representations of ideas or concepts (e.g., texts, sketches, and objects). When a group of students creates physical representations of their learning, they focus on the task and take ownership of the documentation of their learning (Wenger et al., 2002). For example, when a group of students uses a whiteboard to document their discussions, they practice the language of the discipline they are studying (Wood and Kutcher, 2017) while creating a shared understanding of its concepts that is visible to everyone in the same way (Dillenbourg and Traum, 1997), thus constructing a “shared memory” (Dillenbourg and Traum, 2006). The sketches (“objects of knowledge” in pedagogical terms) can be further discussed (Paavola and Hakkarainen, 2005, 2009).

When designing learning situations, teachers continuously make decisions about how to engage students and what kinds of artifacts they ask them to create, and they consider how a series of exercises and instructions can support the students’ learning. When students produce physical representations of their discussions, the instructor can get a good overview of the many discussions taking place in the classroom and better evaluate and decide how to proceed and interact with the students.

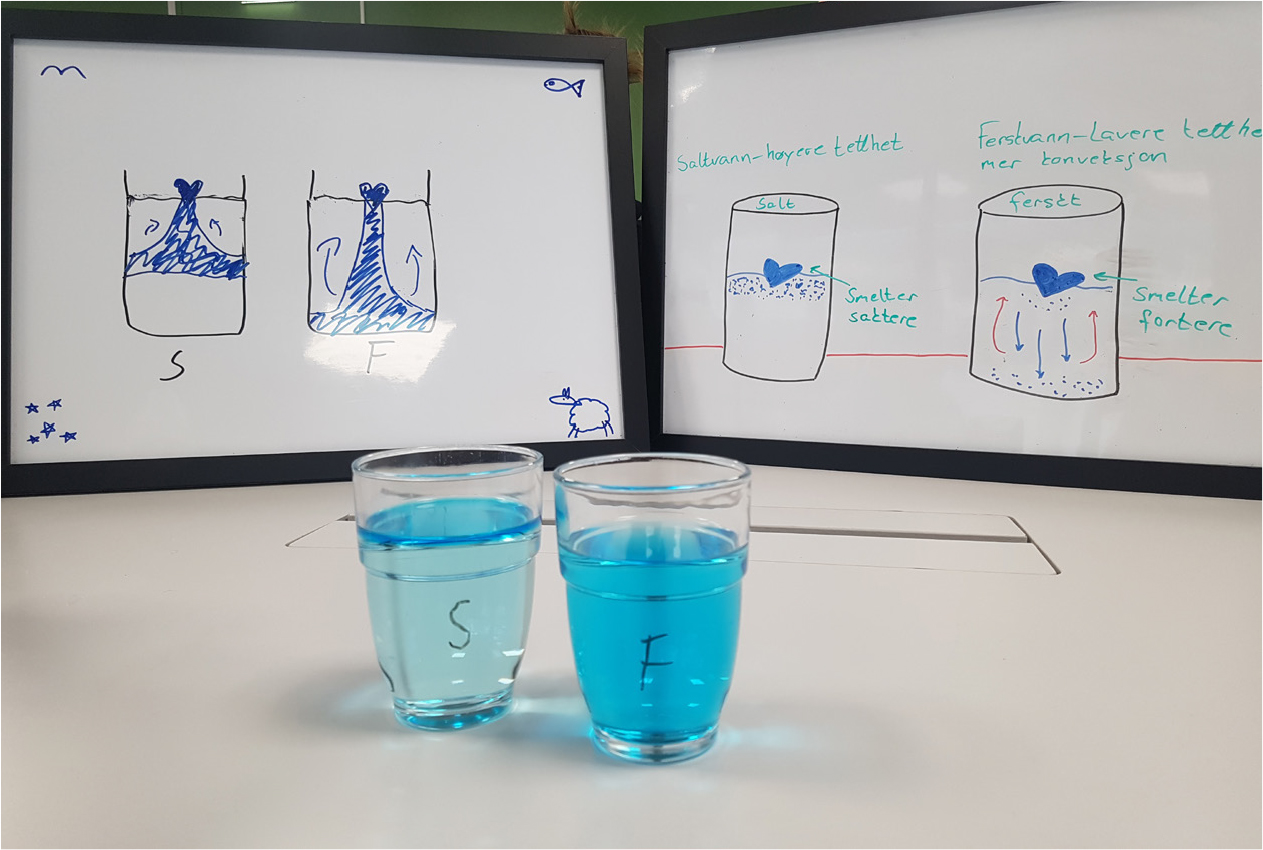

We use collaborative sketching exercises to support students’ sensemaking and help them reach two main goals: (1) development of conceptual understandings of central ocean processes or systems, and (2) development of well-founded and testable hypotheses for various practical experiments. During the collaborative sketching activity, students sketch, negotiate, interact with the teacher or other groups, re-sketch, and try to arrive at final sketches they can explain and that make sense (see Examples 1 and 2).

How to Use Collaborative Sketching

We roughly divide the collaborative sketching activity into four steps:

- Step 1. Establish the boundary conditions. Understand the task, retrieve prior knowledge, and outline the framework for the sketch.

- Step 2. Consider the relevant processes to gain a mechanistic understanding. Make lists of, and sort/compare, important elements and include them in the sketch.

- Step 3. Analyze and conclude. Make sense of the theory and how various processes and systems interact. This is where we bring in experiments, mini-lectures, etc.

- Step 4. Apply the knowledge. Analyze various situations or come up with similar examples.

For the sketching exercises, we use portable whiteboards created from inexpensive A3 frames with white sheets of paper placed behind the glass cover and multiple whiteboard markers. When the whiteboard is lying flat on a table, students can access it from all sides in order to contribute to the sketch simultaneously, and it is easy to erase and update parts of the sketch. Using portable whiteboards also makes it easy to share the groups’ solutions with the class simply by holding up the boards and comparing the different sketches. The teacher can invite students to explain parts of their sketches or summarize the similarities or differences between sketches from different groups.

Our Experiences Using Collaborative Sketching

In our undergraduate oceanography course, students often struggle to make sense of new concepts, such as effects of Earth’s rotation. We find that collaborative sketching exercises help students develop conceptual understandings of central processes, including coastal upwelling, geostrophic balance, Hadley circulation, trade winds, and estuarine circulation (see Example 1). The students follow detailed instructions that lead them through Steps 1–4, and they can also interact with the instructor if they get stuck (see blog post at https://mirjamglessmer.com/sketch2learn/). Sometimes, the student groups find it difficult to reach or agree on conclusions. Instead of providing answers, we support their sensemaking process by incorporating targeted mini-lectures (5–15 minutes) on the theories they need to apply to their specific questions to help them come up with the answers themselves.

|

We also find that collaborative sketching helps students develop well-founded and testable hypotheses for practical experiments (such as melting ice cubes to learn about convection in Example 2). First, the sketch provides a concrete and visual representation of the group’s negotiated hypothesis. By inspecting the sketch, the students can more easily discover whether their idea fits with that of the others or if there are possible mismatches that need to be renegotiated. Second, the sketches help the students discuss a system or a process more thoroughly. When sketching their intuitive suggestions, students often realize that there are pieces of the system or the process they did not consider or that parts of their explanations do not make sense.

|

In addition to supporting the sensemaking process, the sketching activity promotes a collaborative classroom community where thinking is made visible. Students report that they enjoy the activity, and we often see them decorating their sketches, adding happy faces to elements of the sketch (e.g., the sun), or adding wildlife to emphasize geographic locations (e.g., penguins in Antarctica vs. polar bears in the Arctic).

Using low-tech portable whiteboards increases student participation. Students are used to working with pen and paper, and this method avoids the technical anxiety that digital programs or advanced software might induce. The sketching activity also offers students the possibility of choosing different roles because “just talking” is not the only valid contribution. Even if students choose to contribute to the discussion mainly by drawing, they still need to make sense of the discussion, ask clarifying follow-up questions, and find ways to translate the spoken word into a concrete sketch.

Ultimately, we find that when students have agreed on a drawing, they can explain it to their peers or the teacher, because they have made sense of a problem together. If you can sketch it, you can explain it!