Introduction

The use of chemical dispersing agents (dispersants) is one of several options available to responders during an oil spill. Dispersants are typically used on larger offshore spills when environmental conditions preclude mechanical recovery, in situ burning, or allowing natural processes to control the fate and effects of the oil. In the case of the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill in 2010, surface dispersant application was used, and for the first time, subsea dispersant injection (SSDI). The latter approach was undertaken with the objective to reduce the emergence of crude oil at the surface and hence the volume of oil transiting to sensitive coastal and estuarine habitats. Further, SSDI may have provided safer working conditions for first responders and others on scene by reducing occupational exposures to volatile organic compounds. SSDI, however, had an inevitable environmental cost and added chemically dispersed oil (i.e., oil plus dispersant) to the deep Gulf of Mexico. Thus, it is critical that the efficacy of SSDI be considered going forward.

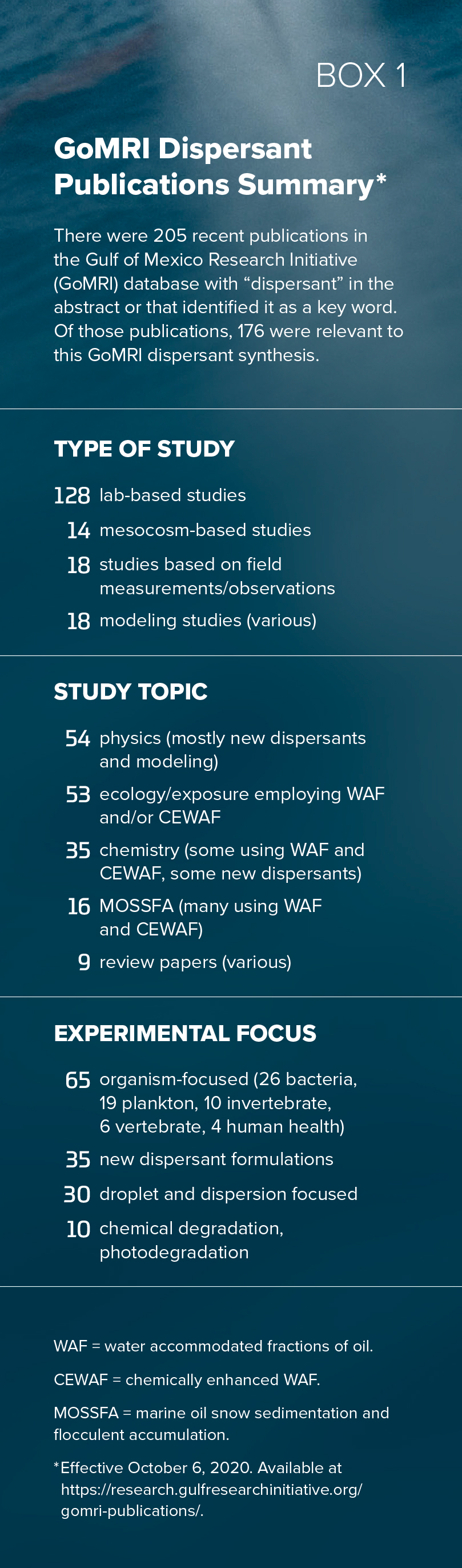

In the September 2016 special issue of Oceanography on the DWH oil spill, John et al. (2016) provided a rationale for the use of dispersants in oil spill remediation. The authors reported on the basic science of dispersants and the creative design of newer dispersants that were offering great promise. Today, there continues to be a need to understand the efficacy of dispersants. This article builds on the earlier synthesis, bringing together new information regarding the fate of dispersants and their effects on ecosystems and humans and, further, summarizes the grand challenges for the future. This review is not intended to be a comprehensive treatise on dispersant research in the last decade. Rather, given that few topics have aroused more public concern than the utility of dispersants to combat an oil spill, this is an effort to bring together the best available science from Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) researchers within the context of work conducted by all scientists, irrespective of the source of funding. Excellent reviews on dispersants, their effectiveness, and ecological impacts prior to the DWH incident are found in the National Research Council reports (NRC, 1989, 2005), while information gathered since the DWH incident is available in Judson et al. (2010), Prince (2015), Kinner et al. (2017), CRRC (2010, 2018), John et al. (2016), Stroski et al. (2019), and NASEM (2020). GoMRI has generated a significant body of knowledge in this arena (Box 1). This review expands on some of the GoMRI-related research cited in the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine publication entitled The Use of Dispersants in Marine Oil Spill Response (NASEM, 2020). In addition, it sets the scene for a forthcoming report from a November 2020 workshop where a synopsis of GoMRI-funded research and other research and assessments was presented and discussed.

|

Role of Dispersants in Oil Spill Response

The goal of dispersant use is to rapidly remove floating oil, a known hazard to diving birds and mammals and the ecosystem as a whole, as well as to reduce the volume of weathered oil that could be transported long distances and affect sensitive nearshore areas, beaches, and marshes. Surface application of dispersants from planes and vessels requires special regulatory approvals that evaluate whether dispersion is possible and beneficial and if the volume of oil transported shoreward into uncontaminated areas can be reduced (IPIECA-IOGP, 2014). In this regard, dispersant application as a tactic in oil spill cleanup has been a well-established intervention method since the 1970s (IPIECA-IOGP, 2014; IPIECA, 2018; NAESM, 2020). Worldwide, there are stockpiles of carefully formulated dispersant products that can be applied rapidly in preapproved areas, for example, United States, United Kingdom, Australia (Carter-Groves, 2014; Global Dispersant Stockpile [https://www.oilspillresponse.com/services/member-response-services/dispersant-stockpiles/global-dispersant-stockpile/]).

Prior to the 2010 DWH spill, dispersants had been applied 213 times at the sea surface (Steen and Findlay, 2008). Over the course of the DWH oil spill, 4.1 million liters of the Corexit dispersants 9500 and 9527 were applied at the sea surface (Figure 1) and an additional 2.9 million liters at ~1,500 m water depth at the wellhead (Figure 1; USCGNRT, 2011; Place et al., 2016). The Corexit class of dispersants used during the DWH oil spill are complex mixtures of surfactants (dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate [DOSS], Span, Tweens) and solvents such as propylene glycol and petroleum distillates (Brochu et al., 1986; Brandvik and Daling, 1998; Riehm and McCormick, 2014). Surfactants are typically formulated from chemicals used as food additives and/or cosmetics, similar to those found in common shampoos and cleaners, including those used to clean oiled seabirds (USFWS, 2003; Hemmer et al., 2011; Word et al., 2015; DeLorenzo et al., 2018). Because of these uses, adverse effects were considered to be minimal. However, recent research has raised questions about these assumptions.

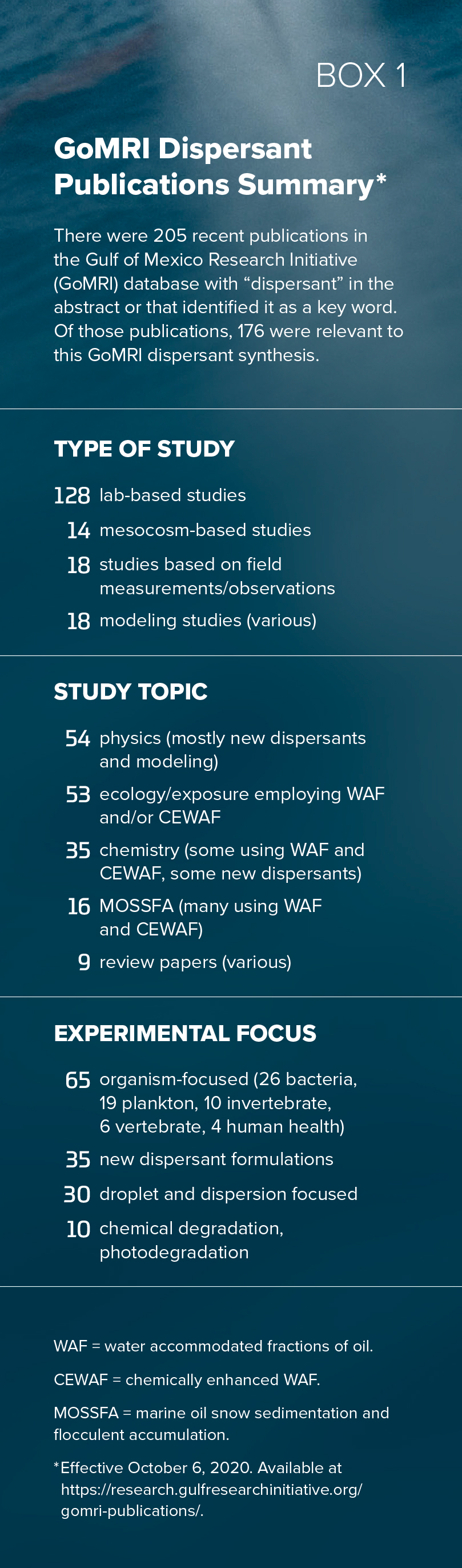

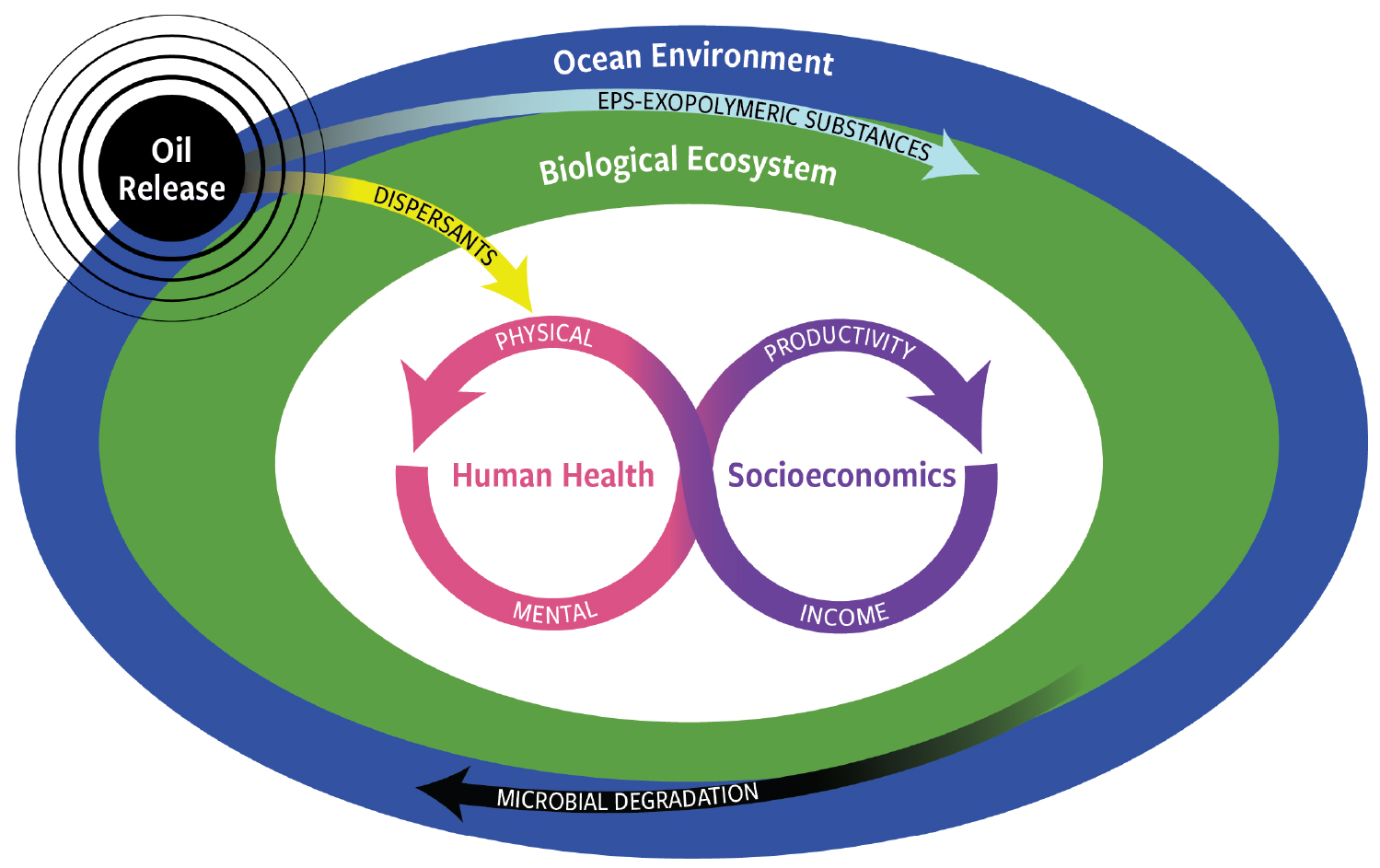

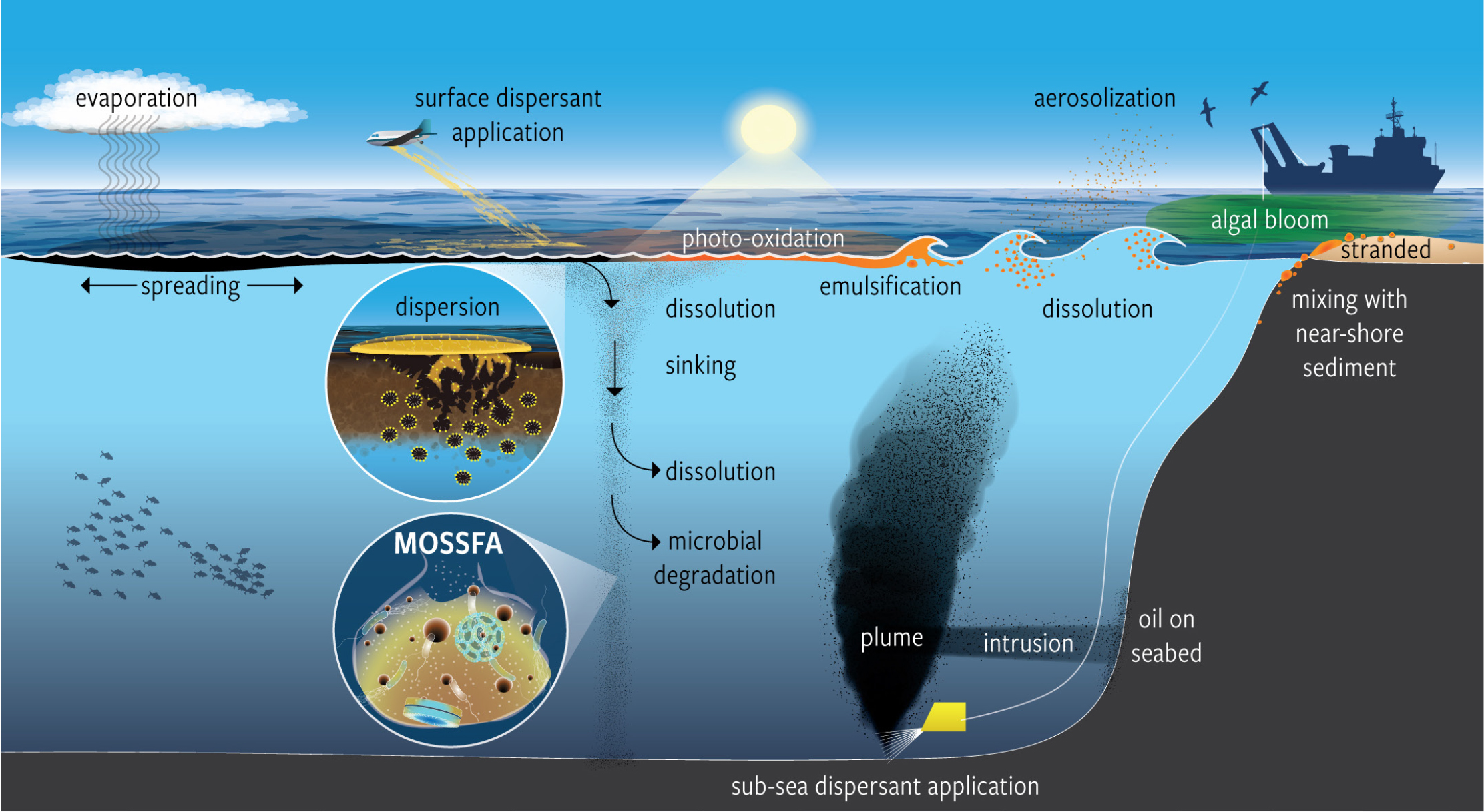

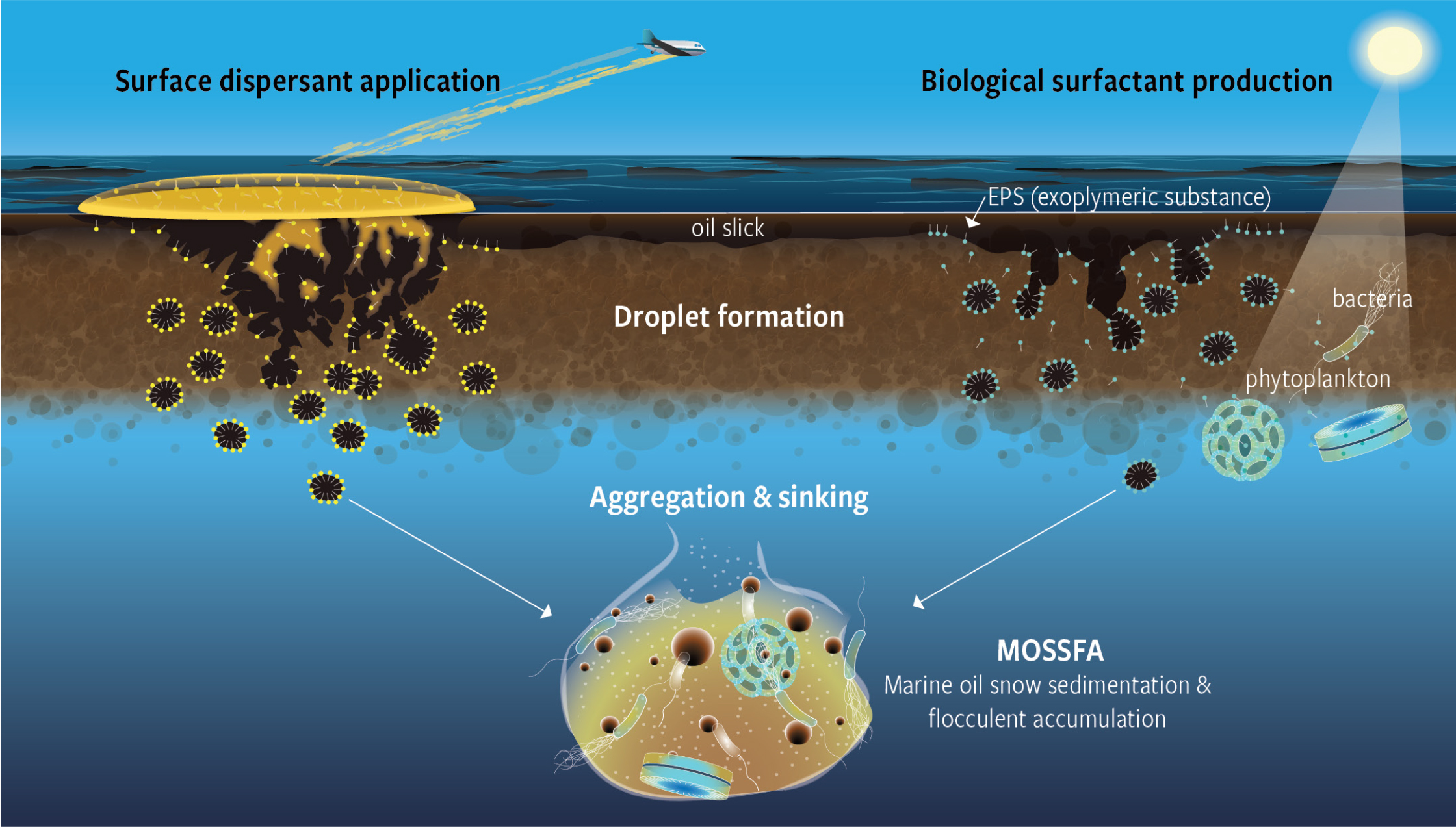

Figure 1. Surface and subsea dispersant injection results in the formation of oil droplets that then undergo a plethora of physical, chemical, and biological reactions. MOSSFA = marine oil snow sedimentation and flocculent accumulation. > High res figure

|

The objectives of using SSDI as a response strategy were to reduce vertical oil transport to the sea surface and subsequent formation of surface slicks, and to reduce the exposure of responders to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that could be harmful to their health and negatively affect operations (Kujawinski et al., 2011; Gros et al., 2017; Paris et al., 2018; Murawski et al., 2019, 2020; NASEM, 2020). Under SSDI, dispersants reduce the ejection turbulence of oil emanating from the wellhead (Figure 1), allowing the formation of tiny neutrally buoyant oil droplets in the deep sea that can be more readily biodegraded (Hazen et al., 2010; Prince et al., 2013; Prince and Butler, 2014). This was also accompanied by a large-scale, horizontally spreading subsea plume of small oil droplets and dissolved hydrocarbons during the spill, in addition to the plume already present prior to the use of SSDI (Camilli et al., 2010; Diercks et al., 2010; Paris et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2014; Socolofsky et al., 2019). In retrospect, plume formation was predicted as an outcome from ultra-deep blowouts (Transportation Research Board and National Research Council, 2003) but had never been addressed to any significant degree in pre-spill contingency planning. Consequently, detailed monitoring protocols were not preplanned and had to be created de novo during the response. These ad hoc protocols did not include the types of measurements necessary to understand fundamental aspects of well dynamics such as the physics and chemistry of multiphase flows with and without the addition of dispersants and the sizes of oil droplets exiting the well. While information was available on biodegradation rates of dispersant components, long-term fate and transport of the more resistant components was not well known. Modeling and experimental work has been undertaken since the spill in an attempt to understand the effects of SSDI on both the quantity of surfacing vs. subsurface oil and whether SSDI reduced the concentration of VOCs around the ship that was drilling a relief well to intercept and kill the blown-out well (e.g., Paris et al., 2012; Gros et al., 2017; French-McCay et al., 2018). At present, there is conflicting evidence as to the efficacy of the use of SSDI (Nedwed et al., 2012; Nedwed, 2017; Gros et al., 2017; Paris et al., 2018; Murawski et al., 2019;

Pesch et al., 2018, 2020).

Fate of Dispersant and Chemically Dispersed Oil

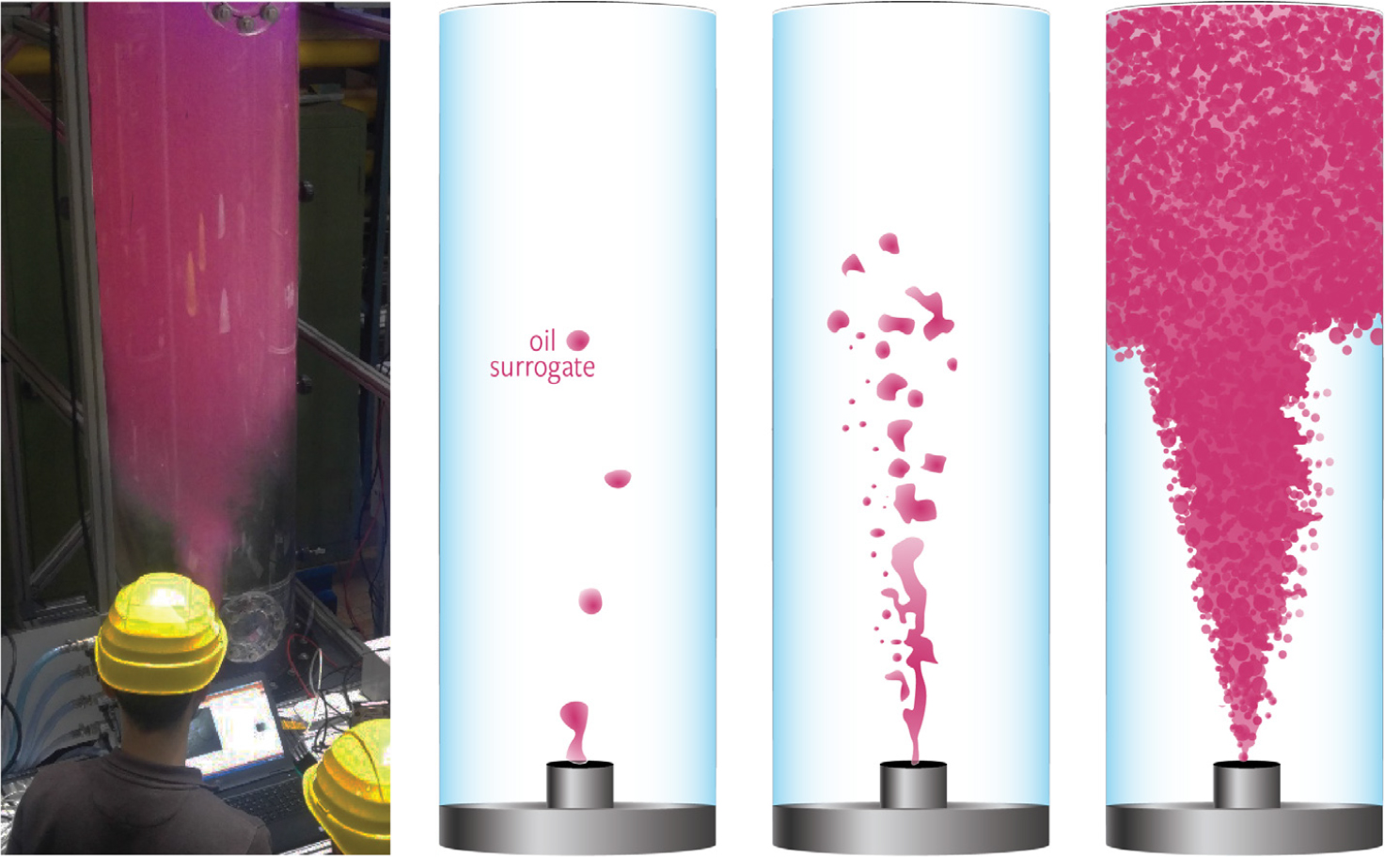

Dispersants partition the oil-water interface to reduce the interfacial (surface) tension sufficiently to create oil droplets (<70 μm) that then stay colloidally suspended in the water column (Figure 2) as they are essentially neutrally buoyant (Brakstad et al., 2015; John et al., 2016). Larger droplets do rise and can (eventually) reach the surface. Partitioning into droplets also allows the chemically dispersed oil to be diluted to very low concentrations for biodegradation by microbes naturally present in seawater (NRC, 2005; Lee et al., 2013; Prince et al., 2013; Aeppli et al., 2014; McFarlin et al., 2014; Prince and Parkerton, 2014; Prince and Butler, 2014; Prince, 2015; Bejarano et al., 2016; Bejarano, 2018). It should be recognized that the enhanced surface area, which is often cited as a major justification for using dispersants, is associated with a surfactant-populated interface rather than a native oil-water interface (Figure 2). In 2010, the US Environmental Protection Agency tested eight of the 14 dispersants listed on the National Contingency Plan Product Schedule, including those used during the DWH incident. Results of these tests showed that a mixture of dispersants and oil was no more toxic than the oil alone (Hemmer et al., 2010). Further, laboratory studies demonstrated that dispersants may be less toxic than the tested oils based on a variety of toxicity protocols (e.g., Barron et al., 2003; Hemmer et al., 2011; Claireaux et al., 2013) where the oil toxicity is primarily shown or thought to be associated with the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) content.

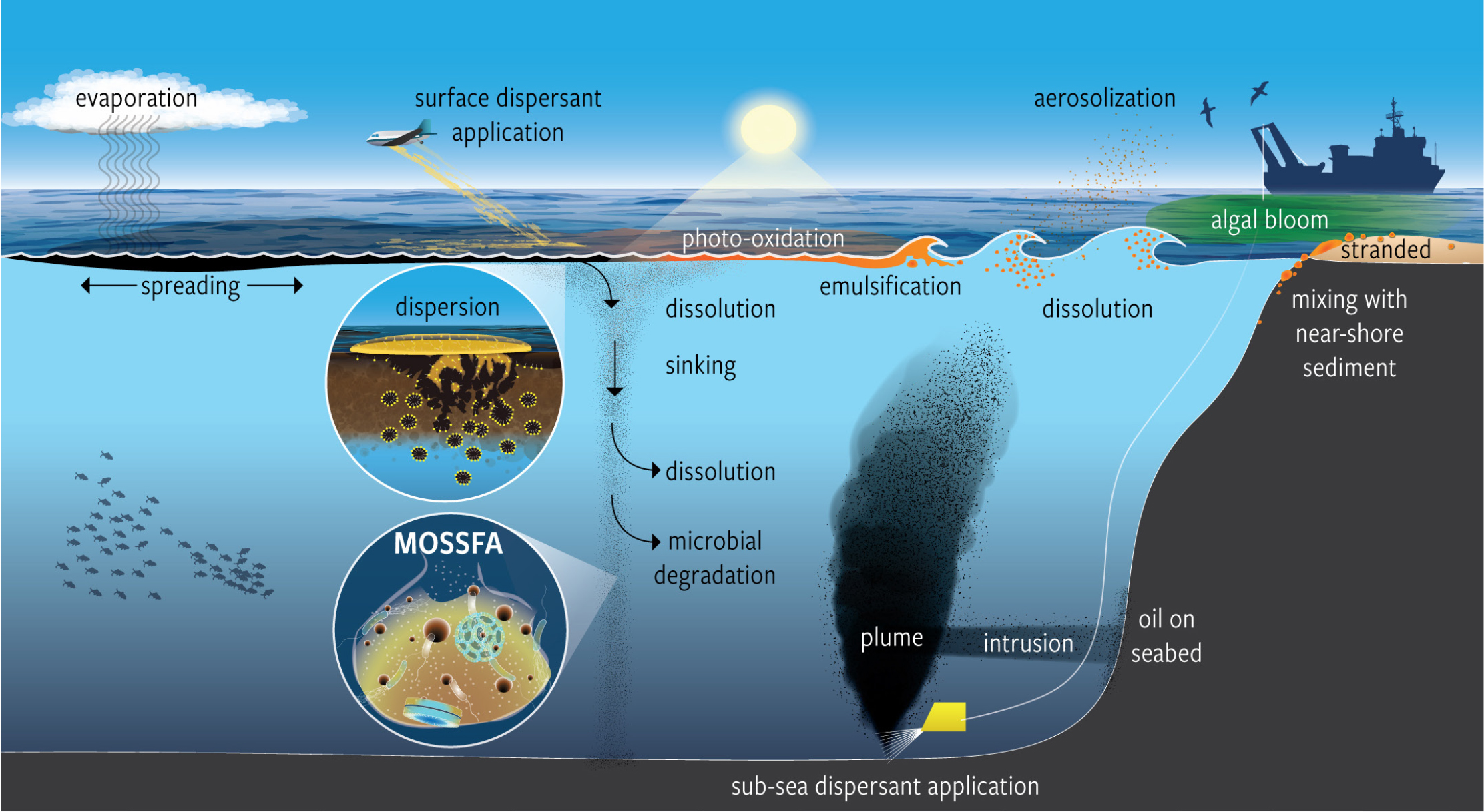

Figure 2. The application of dispersant on the surface slick coats the oil and leads to formation of droplets that are readily dispersed as a result of a range of chemical and physical processes (left side of figure). Microbes (bacteria, phytoplankton) release exopolymeric substances (EPSs) in response to a variety of environmental stressors, including oil and dispersants. An EPS is a biological surfactant that coats oil droplets and chemically disperses them to form marine oil snow (MOS), which aggregates below the surface (MOSSFA) and ultimately leads to the deposition of these materials on the seafloor. (For details, see Daly et al., 2016; Quigg et al., 2016; Burd et al., 2020; Ross et al., 2021). > High res figure

|

Dispersed oil biodegradation rates varied from those identified by Hazen et al. (2010), who measured half-lives of n-alkanes in samples that had spent a few days in the dilute (2−442 ppb), dispersed submarine plume created by the DWH spill at 1,100−1,220 m depth (and at 5°C). Very similar results were reported for a broad array of individual hydrocarbons studied at low concentrations in New Jersey seawater at 8°C, in a flume in Trondheim, Norway, at 30°−32°C, and in water collected off the Penang, Malaysia, shore at 27.5°C. The approximate biodegradation half-life of the total measurable hydrocarbons was 11−14 days, both at low oil concentrations with indigenous nutrients (2.5 ppm and 43 ppm oil, respectively) and at slightly higher concentrations (100 ppm oil) with added nutrients. Even the four-ring aromatic PAH chrysene and its methyl-, dimethyl-, and ethylalkylated forms had half-lives on the order of a month (Hazen et al., 2010; Zahed et al., 2011; Bælum et al., 2012; Prince et al., 2013; Prince and Butler, 2014; Prince and Parkerton, 2014; Brakstad et al., 2015; Prince, 2015). However, smaller oil droplets were also found to result in increased dissolution of potentially toxic oil components and exposure to aquatic organisms (NRC, 2005; Seidel et al., 2016). The fate and transport of the oil and its components is reviewed in detail by Passow and Overton (2021) and by Farrington et al. (2021) in this issue.

Some studies, especially those conducted at higher chemically dispersed oil concentrations, found that dispersants have no effect on microbial biodegradation rates while others show they do (Fingas, 2008; Camilli et al., 2010; Hazen et al., 2010; Kleindienst et al., 2015a,b; Joye and Kostka, 2020; Rughöft et al., 2020). Although some dispersant components are easily metabolized, others may persist for long periods in the environment (Kujawinski et al., 2011; White et al., 2014; Place et al., 2016). After dispersant application during the DWH spill, water samples collected at the sea surface and below showed low (or undetectable) concentrations of DOSS (a biomarker used for Corexit), while water collected in the oil-derived plume contained appreciable amounts of DOSS (Gray et al., 2014). Near the wellhead during the blowout and after SSDI, concentrations of DOSS in the subsurface plume were correlated with dissolved methane concentrations and fluorescence-based measurements of hydrocarbons (Kujawinski et al., 2011). As the plume traveled farther from the wellhead, DOSS concentrations decreased, presumably via dilution (Kujawinski et al., 2011) rather than by biological degradation. DOSS was also entrained in oil that eventually rose to the surface, sank into sediments, or was deposited on corals near the damaged wellhead (White et al., 2014). Subsequent experiments showed that DOSS does not degrade appreciably under the cold and dark conditions of the deep ocean (Campo et al., 2013; Perkins and Field, 2014). Further, the breakup rate of a surface slick ultimately becomes limited to the rate at which surfactants (dispersants) are able to populate the new surfaces (Riehm and McCormick, 2014). Only a small fraction of the surfactants contained in the dispersant is necessary to saturate the oil-water interface of a droplet. By definition then, the remaining surfactant has to partition to the bulk phases: the water-soluble Tween to the water phase and the oil-soluble DOSS and Span to the oil phase.

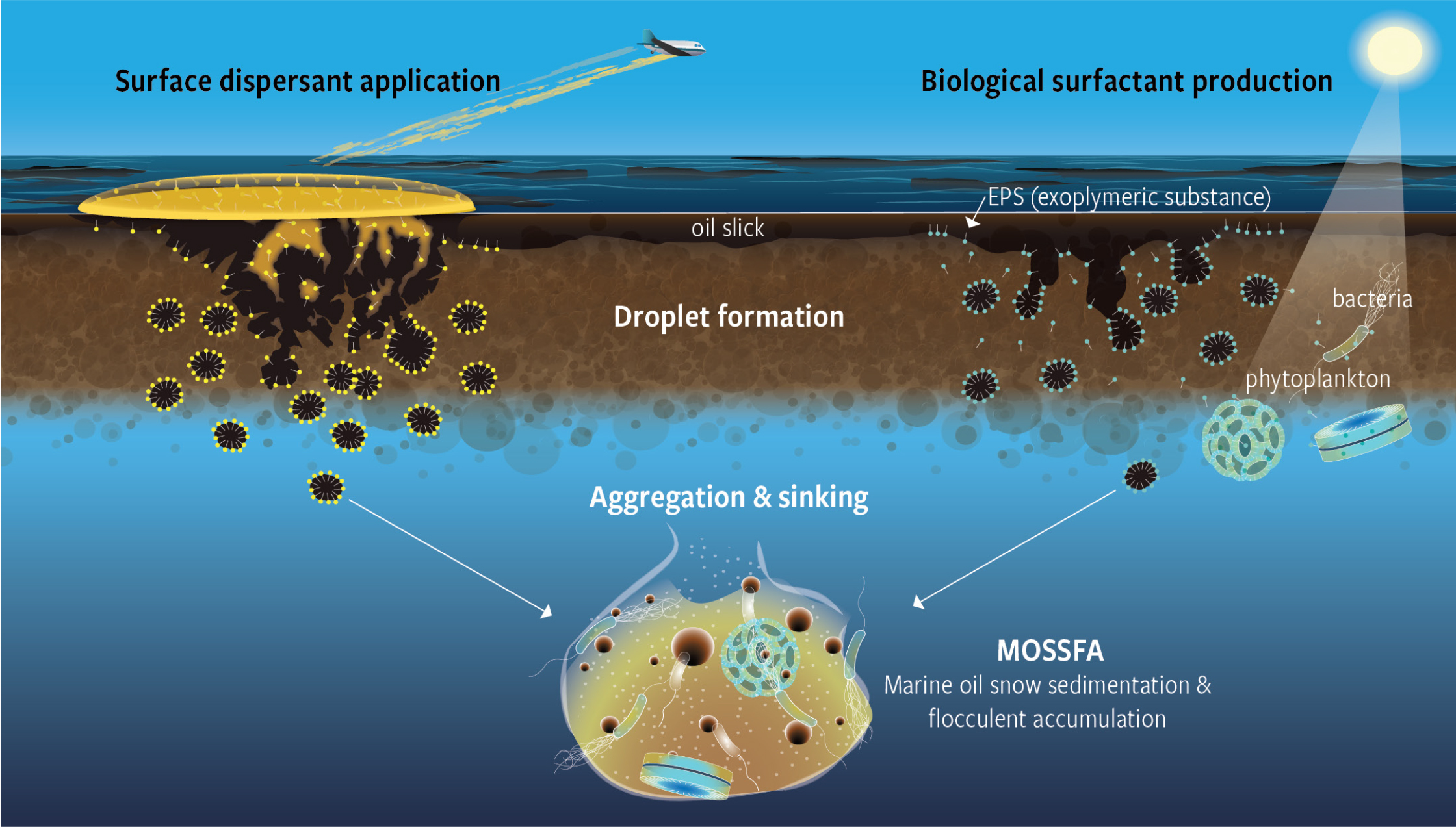

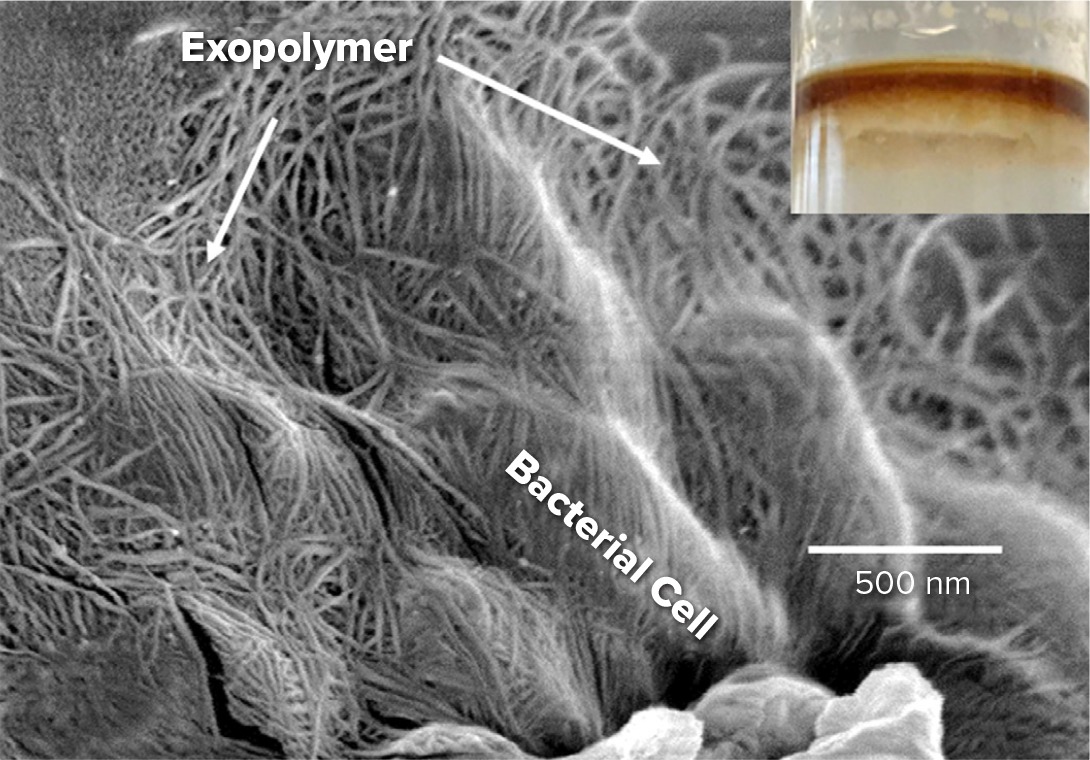

An interesting set of experiments by Reichert and Walker (2013) indicated potential irreversibility of surfactant adsorption at the oil/water interface (Figure 2). Using Tween 80 as a model surfactant, the authors gradually introduced the surfactant in solution to a stationary drop and monitored the decreasing rate of oil-water interfacial tension. Subsequently, there was a shift from a surfactant-containing to a surfactant-free solution, and interfacial tension was monitored to observe the possible desorption of surfactant from the interface. Interestingly, the interfacial tension does not increase significantly, implying a partial irreversibility of adsorption to the interface. This observation has implications for oil-spill remediation using dispersants. Surfactant-coated oil droplets, and excess surfactant in the aqueous phase consisting of swollen micelles, travel in plumes, and dilution into the vast water column may not be as rapid as intuitively expected. There could be exchange of surfactant between the aqueous phase and the droplet interface during such transport. The implication is that if there is a degree of irreversibility in surfactant adsorption, oil droplets will typically contain surfactants at the interface. The two- or threefold increase of interfacial area as droplets form with dispersant application does not necessarily translate to a similar increase in biodegradation rates, as this is a new interface containing surfactants. Indeed, Abbasi et al. (2018) found that surfactant-covered droplets have a strong inhibitory effect on the attachment of the alkane biodegrading organism Alcanivorax borkumensis on the oil-water interface. The hydrophobic effect of surfactant tail insertion into biomembranes is a possible interpretation of such inhibition of attachment. These authors also found that Alcanivorax borkumensis readily attaches to oil-water interfaces in the absence of surfactant and initiates prolific growth of biofilm (Figure 3), an observation verified by Omarova et al. (2019). The presence of particles to stabilize oil-water emulsions further leads to sequestration of Alcanivorax borkumensis and significant biofilm growth (Omarova et al., 2018). Thus, there are a number of fundamental mechanisms that support the observations in some experiments of dispersant-induced reduction of biodegradation.

Figure 3. The alkane degrader Alcanivorax borkumensis forms a prolific biofilm under oil. This biofilm is composed most likely of bacterial released exopolymers, often referred to as EPSs (exopolymeric substances or extracellular polymeric substances). Image from Omarova et al. (2019). > High res figure

|

Dispersant Effects on Marine Life

After an initial decline, benthic animals, mostly invertebrates, in the area around the spill site began to recover and then to increase in biomass and diversity with time (e.g., Wise and Wise, 2011; Montagna et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2016; Schwing and Machain-Castillo, 2020; Schwing et al., 2020). The usefulness of field-derived information for understanding the impacts of dispersants on mobile marine wildlife is limited because these chemicals are never used in the absence of crude oil. As a result, what we know about the toxicity of dispersants is generally from controlled, and mostly acute (e.g., 96-hour), toxicity test results (Bejarano, 2018; NASEM, 2020). In their evaluation of eight commercial dispersing agents used during the DWH incident, Hemmer et al. (2011) concluded they were almost non-toxic to mildly toxic to the fish species inland silverside, Menidia beryllina, and the mysid shrimp, Americamysis bahia, at the concentrations and exposure durations evaluated. In the aftermath of DWH, a considerable number of laboratory-based studies of the toxicity of dispersants alone, crude oil alone, and the combination of the two were undertaken (see the meta-analysis in NASEM, 2020). Concerns with previous toxicity testing are that such studies were not applicable to field-relevant species, especially deepwater forms, and that there may be a synergistic effect between oil and dispersants not accounted for in binary studies (Murawski et al., 2019; NASEM, 2020). The NASEM committee attempted to conduct a meta-analysis of studies to test several hypotheses regarding the toxicity of oil and dispersants by examining study characteristics including the duration of exposure, exposure concentrations, experimental conditions, species being tested, and whether the combination of dispersants and oil was more toxic than the individual ingredients. This analysis proved extremely difficult because water accommodated fractions were manufactured in a variety of ways, chemically enhanced oil concentrations varied, analytical chemistry was not always conducted to verify exposure concentration, and exposure durations differed. Despite these limitations, NASEM (2020) did not find compelling evidence that at low to moderate oil concentrations, chemically dispersed oil was any more toxic than oil alone. At high concentrations, however, the combination appeared more toxic.

There is some indication from field sampling that fishes and other animals were exposed to dispersants, although the evidence is somewhat circumstantial. Ylitalo et al. (2012) conducted extensive monitoring of shellfish and finfish species used for human consumption in a wide area surrounding the DWH site. They determined that the concentrations of both PAHs and the Corexit component DOSS in fish and shellfish muscle samples were generally low. However, as DOSS is also a common component of pharmaceuticals and laxatives, the presence of DOSS cannot be definitively considered evidence of dispersant exposure, but rather only indicates that DOSS is persistent in the environment. If dispersants applied in SSDI were in fact effective at increasing oil droplet and dissolved oil concentrations in deepwater plumes (Figure 1), then they may also account for the elevated exposure levels seen in mesopelagic fishes (Romero et al., 2018) and evident in extensive sampling of the fauna of continental shelves of the Gulf of Mexico (e.g., Snyder et al., 2019, 2020; Pulster et al., 2020a,b). The severe declines of mesopelagic nekton in the region surrounding DWH since the spill (Sutton et al., 2020) is consistent with toxic exposures of this community of invertebrates and fishes to PAHs (and perhaps other toxic chemicals in the weathered crude oil, including reaction products from photo-oxidation and microbial degradation).

Dispersant Effects on Human Health

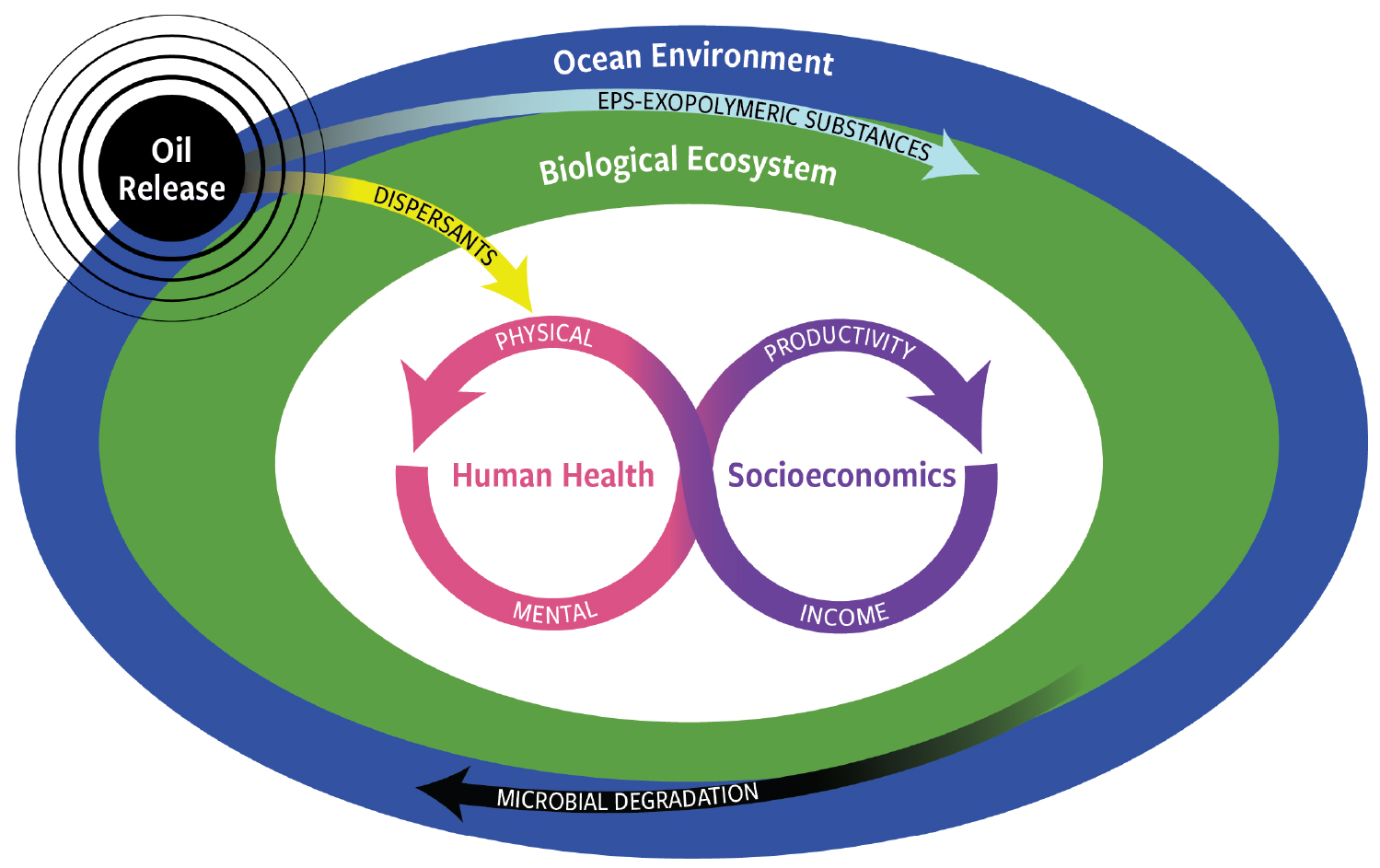

There were several main pathways for human exposure to dispersants (Figure 4) during the DWH oil spill: (1) handling (loading, packaging for spraying from planes, vessels, and subsea dispersal), (2) application (vessel staff spraying dispersants or working on source control vessels monitoring VOCs), (3) passive (e.g., exposure to vessel staff in areas where dispersant was sprayed from airplanes), (4) passive air (e.g., dispersant injected into the atmosphere at the sea surface from treated oil slicks), and (5) indirect (exposures while shutting down or capping the well). In these scenarios, the main pathways for uptake are dermal and respiratory (McGowan et al., 2017). For surface applications, VOCs and airborne fine particulate matter posed the greatest health risks as a result of dispersant application on oil slicks, increasing the total mass burden (Afshar-Mohajer et al., 2018, 2019, 2020). Future studies will, however, be required to determine the applicability of lab findings to natural conditions where other factors are known to modify oil-dispersant mixtures. Further, epidemiological studies found that occupational exposure to dispersants during the response resulted in adverse acute health effects that were still being reported up to three years later (McGowan et al., 2017). In the case of SSDI, less is known about the direct impacts to humans. However, Gros et al. (2017) concluded—based on modeling studies—that SSDI increased the entrapment of VOCs in the deep sea and thereby decreased their emission to the atmosphere by 28%, including a 2,000-fold decrease in emissions of benzene, which ultimately lowered health risks for response workers.

Figure 4. This whole ecosystem view of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill effects and consequences includes impacts beyond the ocean environment and its biological components. Specifically, human health and socioeconomics are key for responding to future spills. For details, see Solo-Gabriele et al. (in press). > High res figure

|

In terms of human health and dispersant application, certainly the mental and social welfare of those who live and work in the region requires more critical investigation (CRRC, 2010; IPIECA-IOGP, 2015; Singer and Sempier, 2016; NASEM, 2020; Solo-Gabriele et al., in press). The adverse health effects for communities of people in coastal areas adjacent to where the large quantities of dispersants were applied well away from land included psychosocial and economic impacts (Figure 4; Solo-Gabriele et al., in press). As summarized by Eklund et al. (2019), studies found dispersant application to be associated with human health concerns, including obesogenicity, toxicity, and illnesses from aerosolization of the agents. Those heavily reliant upon natural resources for their livelihoods were found to be vulnerable to high levels of life disruptions and institutional distrust. Going forward, actions taken to improve disaster response (i.e., media, education, and outreach) can be expected to reduce stress-associated health effects.

Dispersants and MOSSFA

In the weeks after the DWH oil spill, phytoplankton and associated microbes encountered high concentrations of oil and chemically dispersed oil. As a result, these communities formed large-scale exudates of a sticky material rich in proteins and polysaccharides. This material then accumulated cells, oil, and surface inorganic particles into gelatinous flocs that, when combined with clay particles from riverine runoff, sank to the seafloor in considerable amounts (Figures 1 and 2). This abundant marine oil snow (MOS) formed at the sea surface (Passow et al., 2012; Ziervogel et al., 2012; Passow, 2014; Passow and Ziervogel, 2016), and some reports also suggest formation in the subsea plume at 1,100–1,220 m depth (see Burd et al., 2020; Passow and Stout, 2020; Ross et al., 2021). This complex mixture of organic matter, oil, and microbially produced extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) and transparent exopolymer particles (TEP; Quigg et al., 2016). EPSs facilitated access to oil components (Figure 2) and concurrently served as a metabolic substrate for a diverse community of bacteria (e.g., α- and γ-Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Planktomycetales) and phytoplankton (diatoms, dinoflagellates, phytoflagellates) (e.g., Lu et al., 2012; Baelum et al., 2012; Gutierrez et al., 2013; Arnosti et al., 2016; Doyle et al., 2018, 2020; Kamalanathan et al., 2018; Bretherton et al., 2020; Finkel et al., 2020). These observations raise further questions about the effects of dispersant application on microbial activities and microbially catalyzed degradation of oil.

MOS formed in the presence of dispersant appeared to contain more n-alkanes than the oil-only aggregates (Fu et al., 2014; Genzer et al., 2020). EPSs trap oil droplets (see Figure 6 in Quigg et al., 2016) and increase the bioavailability of oil components to microbial communities (McGenity et al., 2012). In this respect, EPS properties are similar to those of surfactants as they reduce the interfacial tension between oil and water and thereby enhance dispersion and potential solubilization and biodegradation processes (Lewis et al., 2010; Gutierrez et al., 2013), including pathways that emulsify petroleum hydrocarbons (Head et al., 2006). EPSs with entrained oil droplets form networks that act as energy and carbon sources for members of the microbial community. This process allows microbes to build biomass. Further, biodegradation does not need to occur exclusively with oil-degrading bacteria directly attached to the oil-water interface (Figure 2). It is quite possible for microbe communities sequestered in EPS films to consume dissolved oil and thus serve as a driving force for oil to partition from droplets to a bulk state. Biosurfactants generated by the microbes can also incorporate oil to form swollen micelles that are more accessible for their metabolism. More work, however, is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms and driving factors for these processes.

Dispersants alter the metabolic pathways of organic matter biodegradation and hence biogeochemical pathways in the ocean. Given that marine snow serves as food for other organisms, this may result in its being repackaged in fecal material that sinks to the seafloor. Via this pathway, marine oil snow sedimentation and flocculent accumulation (MOSSFA) could transfer oil and other chemicals to the food web (Figure 2; Passow and Ziervogel, 2016; Burd et al., 2020). Estimates of the total spatial extent of MOSSFA on the seafloor of the northern Gulf of Mexico range from 1,030 km2 to 35,425 km2 (Passow et al., 2012; Passow, 2014; Daly et al., 2016; Burd et al., 2020; Quigg et al., 2020; Passow and Overton, 2021; Ross et al., 2021). Thus, MOSSFA accounted for a significant fraction of the oil returning to the deep ocean (Valentine et al., 2014; Brooks et al., 2015; Chanton et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2016; Romero et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2018a,b). Recent reviews identify the gaps in knowledge about MOSSFA, focusing on the science (Burd et al., 2020), operational response strategies (Quigg et al., 2020), and oil spill responder and policy decisions (Ross et al., 2021).

How dispersants influence the formation of MOS and ultimately the fate and transport of MOSSFA remains poorly understood. Collective studies conducted under GoMRI revealed the rich complexity of reactions and responses of oil-droplet-dwelling microbial communities with and without dispersants through transcriptomic, metabolomic, proteomic, and concurrently ultra-high resolution mass spectrometry; these techniques collectively revealed that we are only at the tip of the iceberg in our understanding of the complexities of MOS and MOSSFA (Box 1; Figure 2). Given that the effects of dispersant on MOS formation and sedimentation depend largely on the relative concentrations and surface characteristics of the dispersant, marine particles, oil residues, and exudates, future studies might consider how and if novel dispersant formulations will produce the MOSSFA effect. In addition, potential impacts of different combinations (e.g., based on types, formulations) of oil and dispersant on MOS/MOSSFA require investigation as well as the effects of location (e.g., Arctic versus the Gulf of Mexico) as drivers for these impacts. Toxic effects on corals that appear to result from their exposure to oil and dispersant carried by sinking MOS (DeLeo et al., 2016) is little studied and also needs attention. Together, all of this information is critical in order to advance numerical modeling of a simulated oil spill and the trajectories of resulting surface and subsurface flows coupled to satellite mapping. These analyses will provide responders and NRDA trustees information for predicting where MOS may pose significant risk, to whom injury will occur, and how to plan for a spatial and temporal sampling of natural resources at risk (see Ross et al., 2021, for more details). In this way, the NRDA process and other findings can leave a legacy of enhanced preparedness in advance of the next oil spill.

What Are Some of the Grand Challenges Identified by GoMRI Scientists?

GoMRI research has significantly expanded understanding of deep oil spills and the use of dispersants in response to them, but do we know all that is needed to make a scientifically valid response decision for the next major oil spill? Specific to the research conducted by GoMRI scientists, we have identified the following grand challenges in relation to dispersants.

Subsurface Dispersant Injection (SSDI) Application

Use of SSDI was unique to the DWH incident and, consequently, has changed the way in which dispersants will be used in future deepwater blowout scenarios. As part of GoMRI efforts, we learned that SSDI affects transport, biodegradation, flocculation, and sedimentation processes as oil enters and is distributed in a deep ocean environment (e.g., Paris et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2014; Kleindienst et al., 2015b; Lee et al., 2015; Daly et al., 2016; Socolofsky et al., 2019; ). Murawski et al., (2020) identified six important questions regarding the use of dispersants and particularly those delivered as SSDI: (1) How toxic are commonly used dispersants for field-relevant species? (2) Are dispersants + oil more toxic than oil alone or dispersants alone? (3) How effective is SSDI in creating subsurface plumes of small droplets vs. plume effects due to natural processes? (4) Do dispersants increase or decrease biodegradation? (5) Does SSDI reduce the presence of VOCs at the sea surface, thus potentially reducing inhalation exposure to humans and wildlife? (6) What are the trade-offs of sequestering oil in the deep sea by the use of SSDI (subject to the efficacy question) vs. allowing more oil to surface and potentially come ashore? Others (e.g., Prince, 2015) have compared the potential hazards and environmental fate of floating slicks and dispersed oils. We need to determine the best science to address these and other questions.

The difficulty in understanding processes associated with the effervescing “live” oil from a broken well are numerous (NASEM, 2020). No reliable contemporaneous measurements of droplet size diameters at or near the wellhead were obtained during the accident. Furthermore, while some measurements of VOCs at the surface were obtained (Nedwed, 2017), they were not systematic or from fixed locations, nor were the observations controlled for method. Finally, prior to the spill, no high-pressure experimentation had ever been done with a combination of crude oil saturated with natural gas to emulate the actual multiphase flows from a real blowout (see Brandvik et al., 2016). Given the importance of this issue, these data should be revisited, accompanied by new modeling and assessment information.

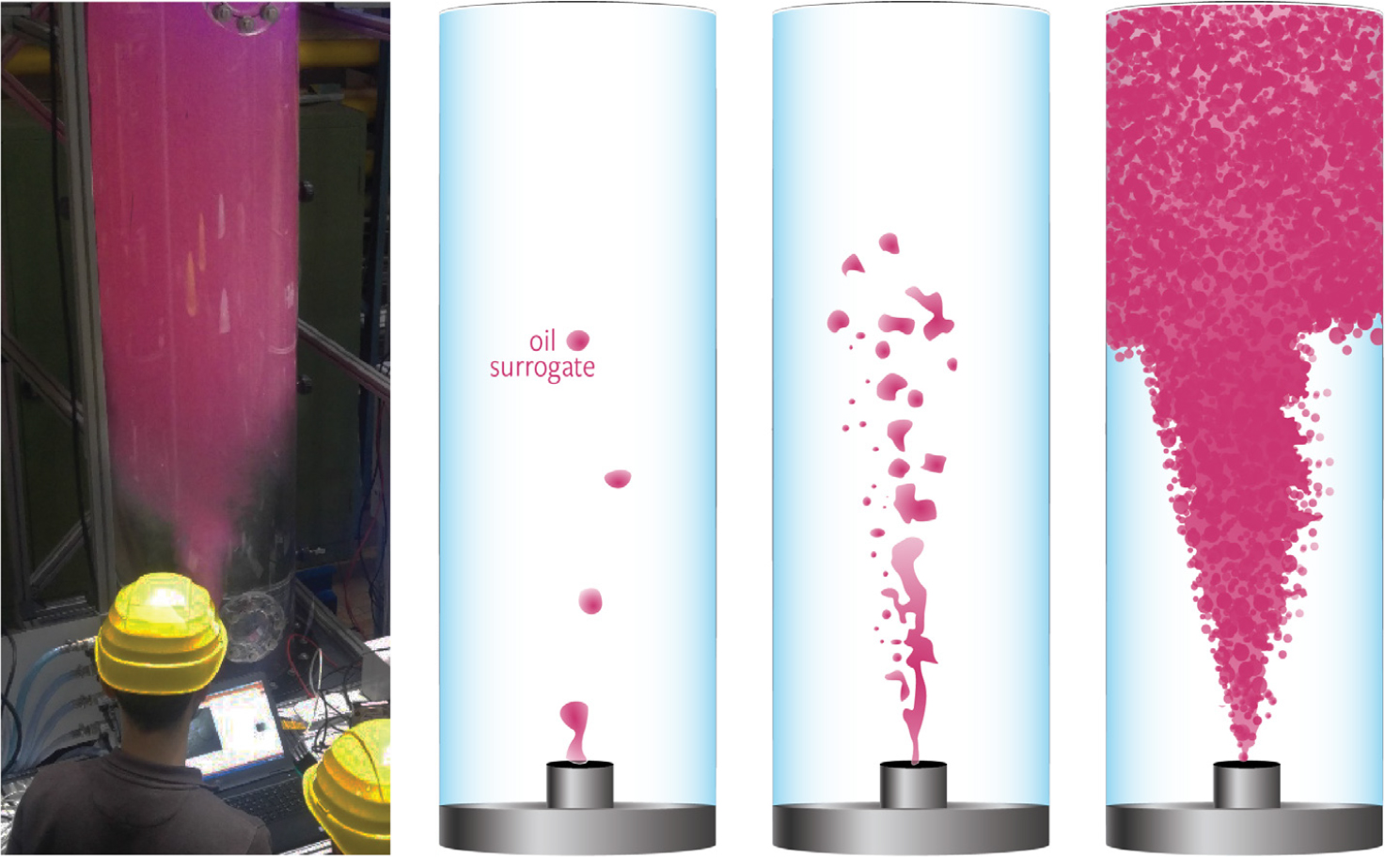

To help resolve the issues of droplet size formation with and without SSDI, and to determine partitioning of oil into its constituents, GoMRI supported the development of high-pressure jet modules and other experimental set-ups (e.g., Figure 5; Jaggi et al., 2017; Malone et al., 2018; Pesch et al., 2018, 2020). Importantly, these experiments included the use of methane-saturated surrogate oils to evaluate the dynamic processes associated with the physical and chemical mechanisms present in an uncontrolled blowout. Chief among the mechanisms investigated were (1) the effect on “live oil” of the over 80 bar, virtually instantaneous, pressure drop at the blowout preventer that led to rapid-degassing, droplet breakup, and the creation of smaller oil droplets; (2) the effects of simulated obstructions in the blowout preventer (such as the partially closed-shear rams) on turbulent kinetic energy and particle size distributions; (3) the decrease in static pressure leading to further outgassing, enhanced buoyancy, and faster droplet rising velocities; and (4) the effects of temperature and pressure on the partitioning rates of various oil-related compounds. Results of all of these experiments support the contention that in actuality the distribution of droplet diameters from the uncontrolled, broken well were much smaller than has been projected from sea level experimentation (Brandvik et al., 2019; NASEM, 2020). Furthermore, even in the absence of SSDI, a substantial fraction of the oil droplets from the well would have been naturally dispersed (Aman et al., 2015; Lindo-Atichati et al., 2016), thus contributing to lateral intrusions of hydrocarbons (Diercks et al., 2010; Kessler et al., 2011) trapped by density stratification of seawater, as described earlier by Socolofsky and Adams (2005). This is supported by the detection of deep oil plumes at the beginning of the oil spill before any significant SSDI use had occurred (Diercks et al., 2010; Paris et al., 2018).

Figure 5. Scientists and engineers evaluate droplet size distributions from oil and gas jet experiments using a surrogate (pink stained) oil. For more information, see Pesch et al. (2020). Left photo courtesy of Michael Schlüter, TUHH, Hamburg, Germany > High res figure

|

As noted in NASEM (2020) and by Murawski et al. (2019), resolving the questions surrounding the efficacy of the use of SSDI is imperative if it is ever again to be included in operational oil spill response. There have been three different suggestions for additional research to more definitively resolve the question of SSDI efficacy, including (1) the use of much larger-scale, high-pressure facilities capable of using live oil, (2) the use of field-scale controlled releases of oil and gas, and (3) waiting for a “spill of opportunity” (e.g., the next deepwater blowout) and employing new measurement technologies and conducting experimentation with and without SSDI (see Murawski et al., 2019). For a variety of reasons, scaling up experimental facilities seems the most practical. As this is inherently an issue of public resource management, support for such a facility should be funded by the oil industry and the government, with appropriate independent scientific oversight.

Experimental Design

Conclusions regarding the relative toxicity of oil compared to chemically dispersed oil are not only species dependent but also influenced by the experimental design (short vs. long term, in vivo vs. in situ) and the chemical exposure measurement unit used to determine the outcome (Coelho et al., 2013; Bejarano et al., 2016; Bejarano, 2018; Mitchelmore et al., 2020; NASEM, 2020), as well as the use of different methods in the preparation of water accommodated fractions of oil (WAF) and, when working with Corexit or other dispersants, a chemically enhanced WAF (CEWAF; see Halanych et al., 2021, in this issue). While some authors used oil and dispersants directly, others worked with WAF and CEWAF fractions. For the former method, a small, but ecologically important, fraction of the oil dissolves in the water and behaves differently than the bulk oil (Liu et al., 2020). We know less about the factors affecting the fate and transport of crude oil water soluble fractions (WSF) in marine ecosystems, despite evidence suggesting that this fraction is enriched during weathering and is more toxic to aquatic organisms than the parent oil (Shelton et al., 1999; Barron et al., 2003; Melbye et al., 2009; Bera et al., 2020). For the latter method, it is difficult to maintain the total concentration of hydrocarbons in the test media due to differential dissolution and dilution of the microdroplets in a WAF preparation, unless these are removed a priori, which few studies do (e.g., Redman and Parkerton, 2015; Kamalanathan et al., 2018; Bretherton et al., 2018, 2020). The toxicity of chemically dispersed oil can be up to an order of magnitude higher than oil that has not been dispersed (Gardiner et al., 2013; Bejarano et al., 2014; NASEM, 2020). These issues impact not only experimental design (variable loading versus variable dilution) but also interpretation of the findings and their relevance to in situ conditions; they are discussed in detail in NASEM (2020).

New Dispersants

Over the decades, exact chemical formulations for dispersants have changed in response to new findings. For example, there were concerns about the adverse health effects in some responders as a result of prolonged exposure to 2-butoxyethanol in Corexit 9527 during the Exxon Valdez accident (NRC, 2005). This solvent is not present in Corexit 9500A, the preferred dispersant for surface applications. In addition, the hydrophobic solvent in Corexit has shifted over the years from hydroformed kerosene to NORPAR (mainly normal alkanes, also called paraffins, therefore the NORPAR), then to ISOPAR (mainly branched or isoalkanes, sometimes referred to as isoparaffins, therefore ISOPAR). Thus, formulations have changed, even if only slightly. Synthetic dispersants enhance dispersion of the oil by natural processes such as wind and wave action (Chapman et al., 2007). The role of new dispersants that work in synergy with Corexit EC9500A, Finasol OSR 52, and Dasic Slickgone NS—the dispersants of choice by the oil industry—remains an area for future studies.

A major challenge to the use of liquid dispersants is the drift of the dispersant spray when aerially applied. Also, liquid dispersants can be washed off when applied to heavy or weathered oils (Nedwed et al., 2008; Nyankson et al., 2014; Owoseni et al., 2014). The use of gel-like dispersants has been proposed to overcome such limitations (Nedwed et al., 2008). Design characteristics for gel dispersants would include a close adherence to oil, a degree of buoyancy that would allow increased encounter with surface spilled oil, and high surfactant concentrations to enable efficient dispersion (Nedwed et al., 2008). Owoseni et al. (2018) showed that polyoxyethylene (20) sorbitan monooleate (Tween 80) can be incorporated into a gel-like phase formed by phosphatidylcholine (lecithin) and DOSS. Inclusion of the food grade, environmentally benign lecithin reduces the need for DOSS, and the system can be translated into a gel when the surfactants are dissolved into approximately equal amounts of water and alkane. The microstructure of the gel as studied through small angle neutron scattering and cryo scanning electron microscopy is one of sheet-like lamelli (sheets of thin membranes) that are rolled up into cylindrical lamelli. These systems are naturally buoyant and break down on contact with oil to release surfactants and reduce interfacial tension to as low as 10–2 mN m–1, producing oil-in-water emulsions with an average droplet size of 7.8 µm. Hence, gels that are buoyant may increase encounter rate with surface oil spills (Owoseni et al., 2018).

Other interesting new concepts in dispersant science include the formulation of dispersants from food grade emulsifiers such as Tween and lecithin, which have been found to be more effective at stabilizing emulsion droplets than Corexit (Athas et al., 2014; Riehm et al., 2015) and the use of engineered particles at the oil-water interface (Omarova et al., 2018). Synergistic aspects of both particles and surfactants have been reported in the design of novel tubular clays (halloysite) containing surfactants within their tubes (Farinmade et al., 2020). Here, the clays act to stabilize the oil-water interface and release surfactant that reduces interfacial tension and decreases droplet size. While the energy of wave action may be insufficient for surface spills, the turbulence at the well head in deep-sea oil spills will allow the formation of particle-stabilized emulsion droplets. Such armored (encapsulated) droplets will not spread as a sheen when they surface but rather will spread as dispersed droplets with hydrophilic exteriors that may possibly be skimmed effectively.

The Future

Given that dispersant application has been an important component of oil spill response since the early 1970s and that dispersants have been used at least 20 times in the United States (NOAA, 2018), it is important to continue to develop a comprehensive understanding about the fate and effects of dispersants and chemically dispersed oil. This understanding will inform updating of the American Petroleum Institute’s Net Environmental Benefit Analysis for Effective Oil Spill Preparedness & Response (API, 2016; IPIECA-IOGP, 2015), the Spill Impact Mitigation Assessment protocols (IPIECA, 2018), as well as the Consensus Ecological Risk Assessment and the Comparative Risk Assessment (see NASEM, 2020). All of these approaches are used by the oil spill response community and key stakeholders to determine what combination of mitigation techniques, including dispersants, offer better protection of environmental and socioeconomic resources. They integrate ecological, biological, socioeconomic, and cultural considerations into assessment strategies. They also encourage stakeholder involvement in selecting the best response options. As the oil and gas industry moves further offshore, deeper and higher-pressure wells are being drilled. A spill would produce new challenges—what shape might these take?

It will also take time and research to determine whether the dispersants themselves, used in such high volumes and at subsea, are in fact effective at what they are intended to do and whether they have any longer-term detrimental effects on marine life and/or public health. Along with the grand challenges identified above, there are further topics that require additional attention. Last, but not least, during GoMRI, as noted above, research has been undertaken to explore alternatives to the established dispersants (e.g., Corexit 9500A) in the United States. As more knowledge is gained about alternative formulations, and perhaps a much more effective and less harmful dispersant is discovered/formulated, there is the pragmatic issue of Corexit 9500A and other dispersants currently listed on the National Contingency Plan Product Schedule that are already purchased and stockpiled in key locations (https://www.epa.gov/emergency-response/ncp-product-schedule-products-available-use-oil-spills). There remains a paucity of information on the long-term consequences of dispersants in the marine environment, as little is known about the fate of household cleaners and products such as shampoos and dishwashing liquids. Thus, the use of these dispersants enters the realm of the interfaces of science-economics-policy management. We submit that the current existence of a stockpile of prepositioned dispersants should not hinder research that could lead to more efficient and potentially less harmful dispersant formulations.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative. We thank all those who participated as we worked to synthesize the syntheses of dispersant work by those funded by GoMRI. We also acknowledge the time and wisdom shared by Chuck Wilson (GoMRI), Peter Brewer (MBARI), Ann Hayward Walker (SEA Consulting Group), Nancy Kinner (Coastal Response Research Center), Victoria Broje (Shell Projects and Technology, Houston), Jürgen Rullkötter (University of Oldenburg, Germany), Claire B. Paris-Limouzy (University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science), Michael Schlueter (Technische Universität Hamburg), and Peter Santschi (Texas A&M University at Galveston). In addition, this synthesis effort would not have been possible without the tremendous support of Michael Feldman (Consortium for Ocean Leadership), who kept us all moving along with an iron fist and gentle laugh. Figures 1, 2, 4, and 5 were prepared by the amazing Natalie Renier (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution). Last but not least, we thank the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.